Covid: Fears of 'impending doom' in Pakistan

- Published

Mahwish Bhatti is one of Pakistan's lucky few - she has been vaccinated

For Mahwish Bhatti, choosing a private laboratory to be vaccinated against the coronavirus was a last resort.

"I was desperate. I panicked," the 35-year-old from Lahore, Pakistan, told the BBC over the phone. "My mother was still waiting for her second dose of the vaccine, so I thought my turn would never come. I thought to myself, I will just buy whatever vaccine is available."

Bhatti, who lost her job recently, had to pay more than 12,000 rupees ($78; £56) to a private lab from her personal savings to get the Russian-made Sputnik V jab. She laughingly adds: "I did get one jab of vaccines, but also one jab to my wallet."

But the decision may yet turn out to be one of the best she has ever made. Bhatti is now among the less than 2% of the country to receive a dose so far - able to skip the long line by paying a price out of reach to many Pakistanis.

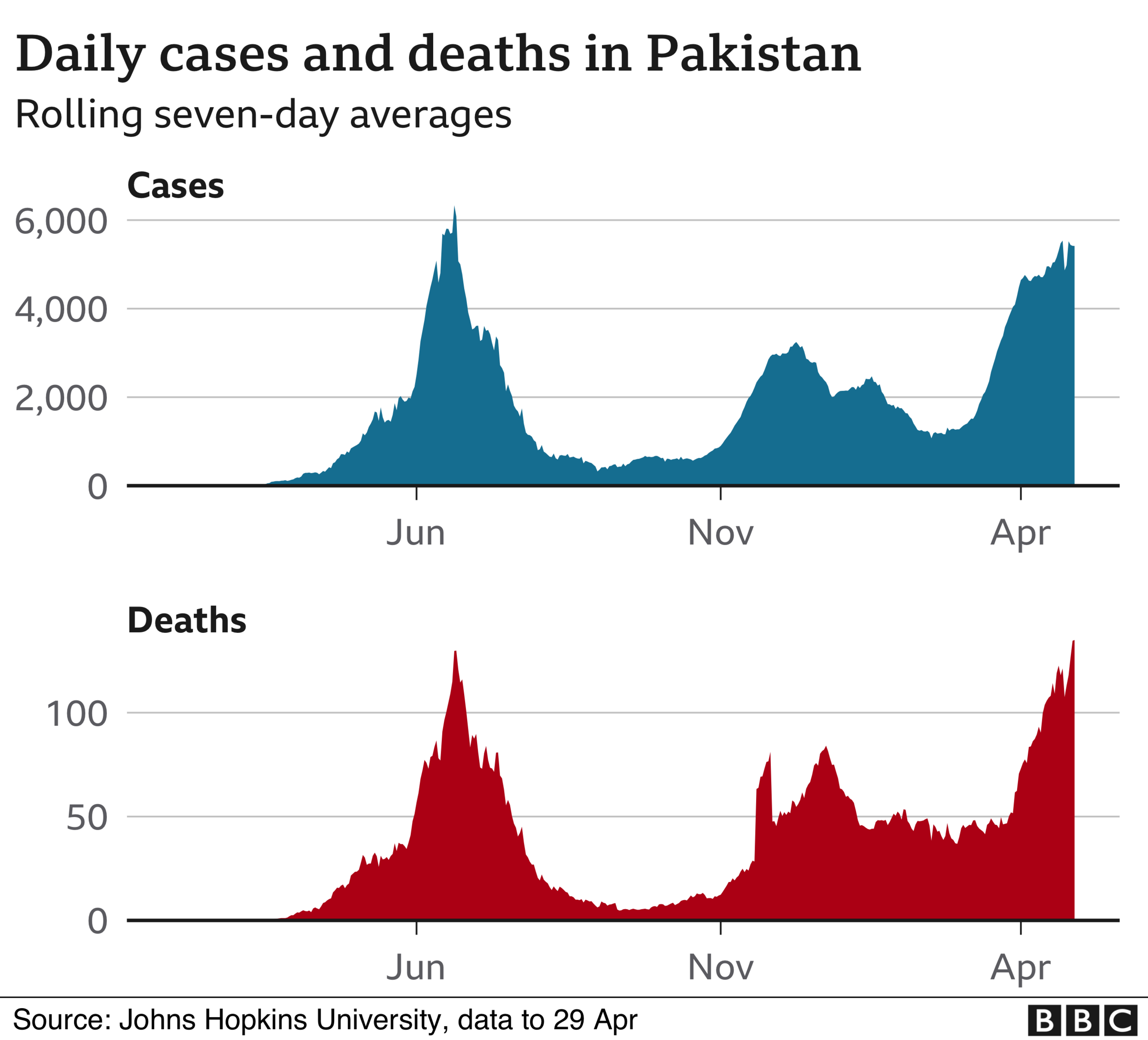

And now cases are on the rise, hitting record highs this week. The funeral pyres burning just across the border in India are a stark reminder of just how quickly matters can escalate when it comes to Covid.

Already Pakistan has seen active cases go from as low as 16,000 in the first week of March, to more than 140,000 new cases in April alone, as well as over 3,000 deaths - making it the worst month since the pandemic began.

Official data reveals that bed capacity in the intensive care units (ICUs) of Lahore's major public and private hospitals reached more than 93% on 28 April, while some of the major cities in the largest and worst-hit province, Punjab, are seeing over 80% utilisation of ventilators and beds with oxygen.

Should the number of infections continue to grow, Pakistan may not just be facing a shortage of beds. Federal Minister for Planning Asad Umar pointed out, external the country was already using 90% of its oxygen supply, with more than 80% already going towards healthcare needs.

Prime Minister Imran Khan has warned Pakistan - with less than one doctor per 963 people - could be headed for disaster.

How did Pakistan get here?

One of the key drivers which led Pakistan to this stage was the arrival of the UK variant, as confirmed by Umar during second week of March. He later declared it, external to be more dangerous than the original strain.

But the variant has collided with something else: apathy.

2020 and me: Mahnaz Rehman lost her husband during lockdown in Karachi

"After the second wave, people thought this is it, it's over," says Dr Seemi Jamali, executive director of the Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre (JPMC), one of Karachi's largest public hospitals.

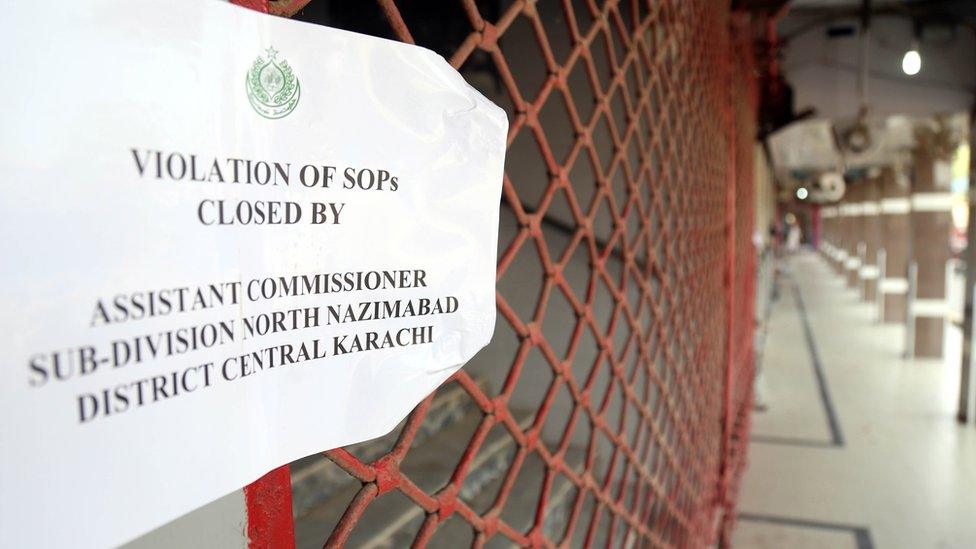

"There was barely anybody following standard operating procedures (SOPs), such as mask-wearing and maintaining social-distancing. Even in the hospitals, people are just not careful."

Indeed, Pakistan came out of both its first and second waves relatively unscathed. The first surge came during May and June last year, but flattened within a few weeks. A second wave emerged around mid-September, and lasted until late February.

More than 800,000 people have been infected since the first Covid-19 patient was identified in Pakistan in February last year, external, with more than 17,000 deaths over the following 14 months. But in a country of more than 216 million people, the absolute numbers don't amount to much.

The problem is no one is quite sure how Pakistan avoided being badly hit initially. Dr Jamali suggests "luck" played a role. Others have different ideas.

Large groups are still meeting despite rising cases

"To be honest, we are still not sure why our first wave was relatively short-lived," said Dr Syed Faisal Mahmood, section head for infectious diseases at Karachi's Aga Khan University Hospital (AKU).

"In retrospect it may have been because of very stringent lockdowns that were instituted early on, amongst other factors."

But the prime minister is not keen on another lockdown. Khan said as much in late April, external, explaining he doesn't want to take any steps which will cause strife for daily wagers and the labouring class.

However, he did leave the possibility open "if our circumstances become the same as India".

Avoiding 'impending doom'

But Pakistan's provinces, which have taken decisions on their own since the pandemic started, may yet take things into their own hands.

After a strict two-week national lockdown last March, the governments, both federal and provincial, moved to "smart" or "micro" lockdowns, focusing solely on areas which were more severely affected, a tactic which remains popular - although critics remain unconvinced of their effectiveness.

For Dr Jamali, delaying a lockdown - even with the extra measures like closing schools, making restaurants takeaway only and calling in the army to enforce mask wearing and social distancing - is unacceptable.

Rules are being more strictly enforced as cases rise, but no lockdown has been ordered

"It is my personal view that strict measures have to be taken. They need to go for a big lockdown and lay down a marker. Merely threatening with a lockdown is not going to work because people have become defiant. The government needs to show its writ for the greater good of the country."

"We still haven't stopped gatherings such as weddings and functions that are causing the spread of this disease," adds Dr Naseem Ali Sheikh, lead for Covid-19 response in Lahore's Hameed Latif Hospital.

"With Eid approaching, the masses are on the streets, and no one is ensuring precautions. Just setting laws is not sufficient, enforcing them is essential to avoid the impending doom."

There is, of course, another way to control the virus: vaccinations.

However, plans to vaccinate to 50% of the total adult population by the end of this year seem miles away.

According to Dr. Faisal Sultan, external, Special Assistant to Prime Minister Khan for Health, Pakistan has given just over two million doses since the vaccination drive began on 2 February.

That amounts to 0.95 doses per hundred people, external. India, which began its vaccination programme in January, has managed to give out over 144 million doses, roughly 10.5 doses per hundred people.

A packed vaccination centre in Karachi

Pakistan has also so far secured just 18 million doses, of which the country has received only just over five million doses, Dr. Sultan said. According to data compiled by the Duke Global Health Innovation Centre, the country requires at least 86 million doses., external

The Economist Intelligence Unit says in its report, external that Pakistan will only achieve widespread vaccination - which means 60-70% of its adult population - by early 2023.

Dr Jamali of JPMC believes that disinformation and fatalistic attitudes towards vaccines are playing a role in slowing down the programme. However, she also adds that the "vaccine procurement process by the government has been very slow".

On the other hand, Dr Sheikh says that while the government has managed to pursue an effective vaccination campaign with an easy-to-understand process for registration and vaccination, it isn't sufficient.

"This is unfortunately not enough as the majority of our population does not understand the concept and purpose of vaccination. The campaign needs to include awareness and along with it, more strict SOPs need to be ensured," he tells the BBC.

For Mahwish Bhatti, despite receiving her second jab of the Sputnik V vaccine recently, there isn't much light at the end of the tunnel.

"The rollout process is so slow. I sometimes wonder when my age group's turn to get vaccinated will come. I was perhaps lucky enough to purchase doses for myself, but what about a common man, a daily wager? They don't have this much spare. How will they get it if there is no vaccine?"

Additional reporting by Benazir Shah, a Lahore-based journalist.

Related topics

- Published21 August 2020

- Published10 July 2020

- Published30 July 2020

- Published29 January 2021

- Published30 December 2020

- Published7 December 2020