Pakistan: The man trying to improve women's underwear

- Published

A former M&S employee is hoping to bring M&S quality underwear to Pakistan

There are many places one might expect to be prevented from entering by security guards. In Pakistan, that place may well be a lingerie shop, where a combination of taboo and a lack of women at the top combine to ensure comfortable, well-fitting underwear remains the preserve of the rich.

Fifteen months ago, Mark Moore found himself blocked by two men at the entrance to a tinted-windowed store in Pakistan's capital, Islamabad. What, they asked, did he think he was doing going inside a ladies undergarment shop?

They let him go when Mr Moore's friend lied that he was a diplomat buying underwear for his wife.

But in fact, the Leicester-born businessman was conducting research which he hoped would help him complete his mission - to bring high quality, affordable and comfortable underwear to the women of Pakistan.

The problem is, the security guards were just one of the obstacles in his way.

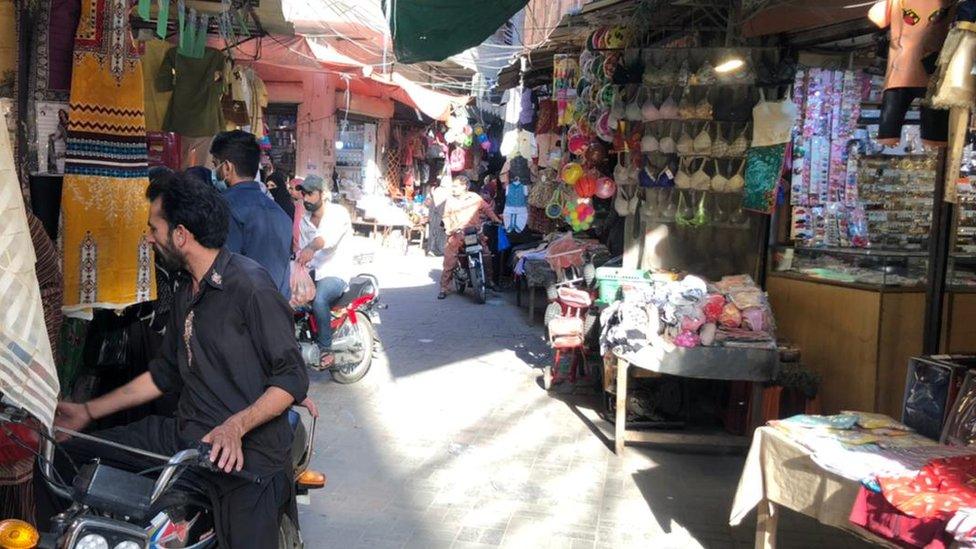

Women complain about the poor fit and bad quality of the products bought in local markets

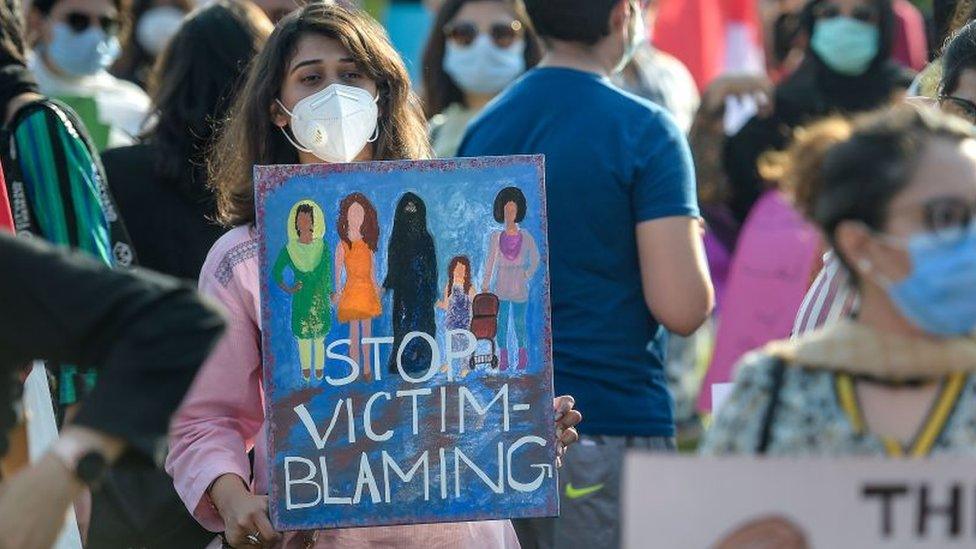

At a basic level, it comes down to the fact men and women have very different ideas when it comes to underwear. And when it comes to men, that generally tends to mean "sexy and appealing", explains Mr Moore.

"They talk and decide on laces and see-through fabric etc.. Whereas women want comfort and reliability of the product they use."

For the majority of the women in Pakistan - unable to afford the expensive imports - that comfort and reliability is something they can only dream of. Most of the affordable options are known to have clasps which rust and sharp underwires which worm their way out to poke the wearer's skin.

"In the past 10 years, I never found my size or the bra shape I wanted," Hira Inam, 27, told the BBC as she stood outside Anarkali market in Lahore. "The material is often not good. It constantly itches and in case of sweating I get a rash around the cup as the material is just not comfortable."

Her words are echoed by others in the market.

"I have spent a lot of money, time and energy on finding a bra that fits or that is comfortable against my skin," another woman says, refusing to give her name. "But I have failed so far. The wiring in the cup is the first thing to come out. And it can really damage the skin if one is not careful."

These bras are openly displayed, but higher end products are generally hidden behind tinted windows

So the demand for high quality, affordable underwear is clearly there - and yet Mr Moore's products, made in a factory in Pakistan's textile industry hub, Faisalabad, and inspired by his years working for British staples M&S and Debenhams, are not yet flying off the shelf.

But why?

For a start, not many people know about them. Marketing to Pakistan's women is proving a little tricky. Underwear - or at least, any discussion of it in the public arena - is taboo.

In time gone by, word of mouth has proved key. Thirty years ago, retailers offering a good quality, well-fitted undergarment in Karachi's packed Meena Bazaar could rely on an almost instant surge in sales based on personal recommendations.

For women living further afield, magazines would offer up carefully chosen adverts to tempt buyers.

But with the switch to digital, these magazines have fallen by the wayside. Meanwhile, a social media campaign - possibly the best way to get word out in modern Pakistan - runs the risk of getting the product labelled "vulgar".

Mark Moore's factory in Faisalabad is now producing mid-range products

And it's not like women can be tempted into a shop by a window display. As Mr Moore discovered all those months ago, most underwear shops are unbranded and boast tinted glass - meaning many of the people walking past would struggle, as he had, to guess what it sells.

There are some shopping centres where underwear shops are more prominent, but these are only used by a select few.

Mr Moore was advised his best bet was to join up with a larger retailer or big brand - and that means explaining the concept of safe, affordable and un-sexy underwear to those boardrooms filled with men.

"Once my team and I put the product, that is the bra and panties, on the table, men giggle," he says.

"My biggest struggle right now is to let most people know that bras and panties are not a product that titillate," Mr Moore adds.

"It is a product of ease and comfort of the user and we should normalise its buying and selling."

It seems a long way off, though.

Mark Moore says one of the biggest barriers is the idea underwear does not have to titillate

In most manufacturing companies and brands that Mr Moore visited, a majority of the officers and designers approving undergarments are men.

"We have to pitch the ideas to these men," explains Qamar Zaman, operations manager of the factory in Faisalabad.

"And women are either assistants and called in to give suggestions. But it is an awkward conversation where the woman is not comfortable sharing ideas about what she liked in an underwear in a boardroom full of men."

Their own attempts to get women to take more senior roles at their own factory have not had great success, though.

"We did send advertisements looking for women for staff and higher position roles, but we had people saying that they will speak with their families and get back to us," Mr Moore explains.

The subject is so taboo some women have not taken up jobs at the factory

"We had two people who came back and said their families do not want them to work in an undergarment factory."

Indeed, such is the taboo that those discussions played out multiple times across the factory floor.

Staff member Sumaira revealed that her husband accompanied her to the interview.

"Once I was hired, my husband asked me to not tell other family members where I work. Because they will make an issue out of it."

Similarly, another staff worker said that she had asked her father before going to the interview for the post of lockstitch worker.

"And my father instantly refused to listen," she said. "I had to ask him to let me go and see for myself and if in case I don't like the atmosphere at the factory, I won't accept the job."

Men have also had to tackle raised eyebrows and whispers though.

Staff member Anwar admits he was initially embarrassed

Anwar Hussain told the BBC he faced a lot of opposition from his family and friends in the beginning.

"My friends made fun of me about where I work. My family refused to let me go to the factory. When I eventually joined, I initially felt shy passing on the stitched bra to another female colleague. I feel much better now and feel comfortable. Because at the end of the day it is a job."

Now the factory workers have other worries, however. If this doesn't work - and work quickly - Mr Moore may decide it is simply too difficult, shut up shop and leave countless staff members in the lurch.

This is not, however, the case, he assures the BBC.

"I have been told that I should look for something alternative to do in Pakistan, as it is a losing idea to sell underwear," he acknowledges. "And yes, there is a perception that I may leave.

"But I'm very much here until this product comes out in the market."

You may also be interested in...

A tour of Lahore's largest second-hand clothes market, Lunda Bazaar, in Pakistan.

Related topics

- Published24 October 2019

- Published22 November 2019

- Published7 April 2021

- Published16 October 2017

- Published28 August 2015