Afghanistan: Black Hawks and Humvees - military kit now with the Taliban

- Published

A video recently posted on social media showed Taliban fighters looking on as an iconic piece of US materiel (military hardware), external - a Black Hawk helicopter - was piloted across Kandahar airport.

The four-blade multi-purpose aircraft was just taxiing on the tarmac, but the exercise sent a message to the world: the Taliban were no longer a group of ragtag soldiers wielding Kalashnikov assault rifles on battered pickup trucks.

Elsewhere, since the fall of Kabul on 15 August to the hard-line Islamist group, the Taliban's fighters have been pictured showing off a host of US-made weaponry and vehicles.

Some of them were seen in complete combat gear in social media posts and couldn't be distinguished from other special forces from across the world. There was no characteristic long beard, or traditional salwar kameez outfit, and certainly no rusted weapons. They looked the part.

They seized these weapons after troops from the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces (Ands) surrendered one city after the other.

Some on social media said this made the Taliban the only extremist group with an air force.

How many aircraft does the Taliban have?

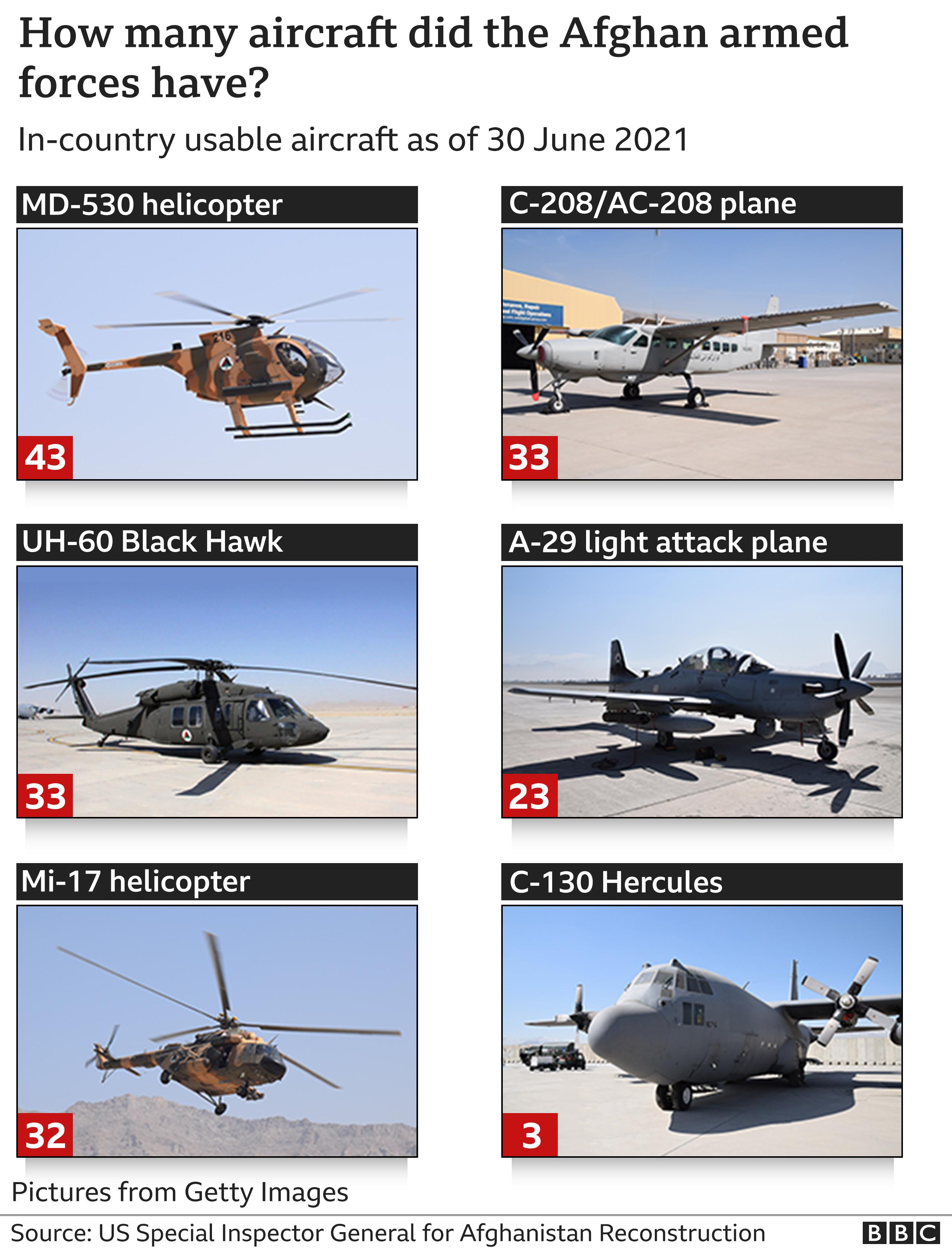

The Afghan Air Force was operating 167 aircraft, including attack helicopters and planes, at the end of June, according to a report by the US-based Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (Sigar).

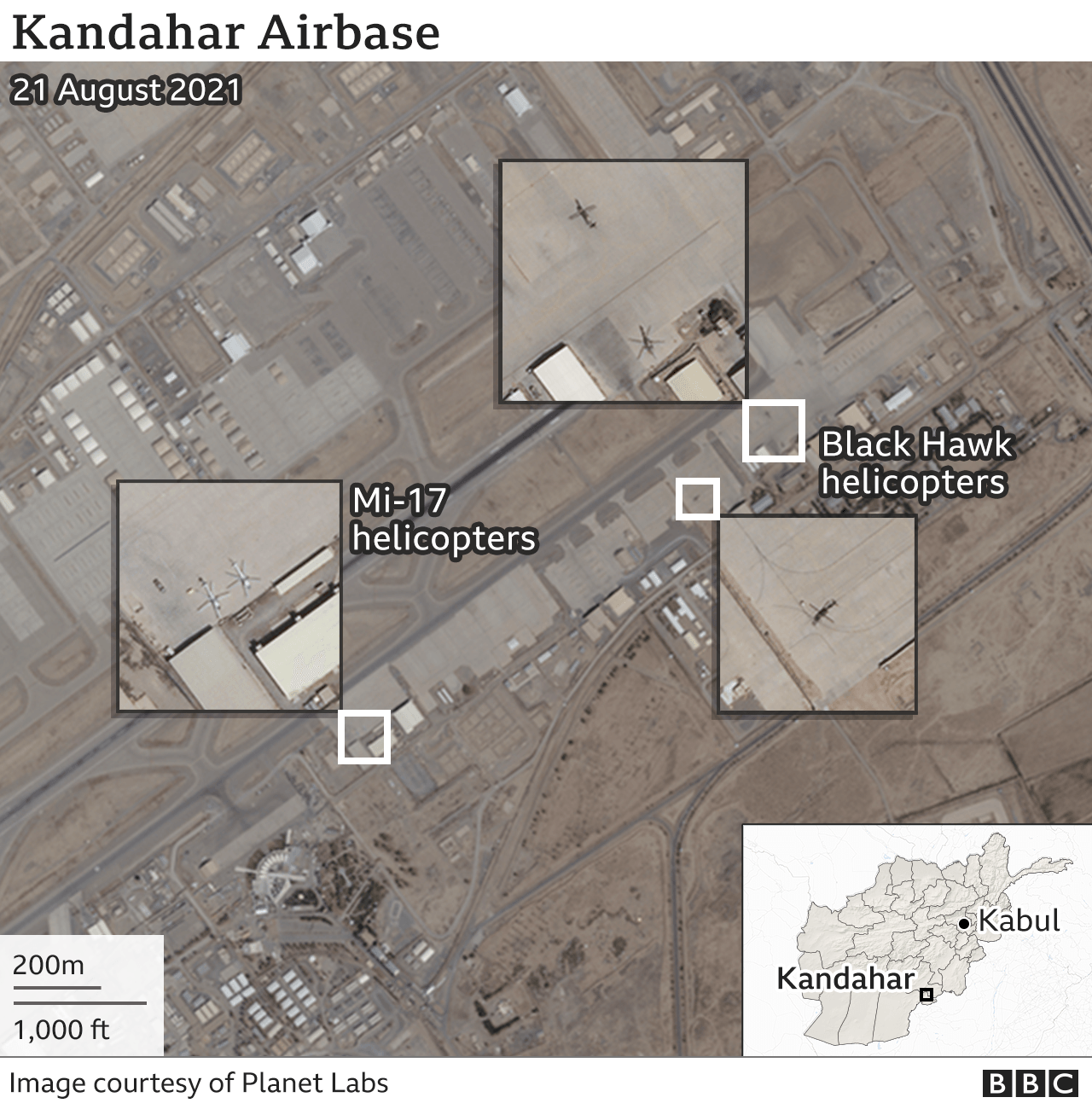

But it's unclear how many of those 167 the Taliban have actually captured. Satellite images of Kandahar airport, given to the BBC by Planet Labs, show a number of Afghan military aircraft parked on the tarmac.

An image from six days after the city was taken over by the Taliban shows five aircraft - at least two MI-17 helicopters, two Black Hawks (UH-60) and a third helicopter which could also be a UH-60, according to Angad Singh, a military aviation expert at Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation.

In contrast, 16 aircraft - including nine Black Hawks and two MI-17 helicopters and five fixed-wing planes - could be seen in another satellite image taken on 16 July.

It means that some of these aircraft were either flown out of the country or moved to other airbases.

The Taliban has also captured the remaining nine Afghan airbases, including those in Herat, Khost, Kunduz and Mazar-i-Sharif - but it's not clear how many aircraft they have seized from there as satellite images are not available from these airports.

Taliban fighters and local media have been posting images of confiscated aircraft, external and unmanned drones from these airports. Some independent websites have also geo-located some of the aircraft.

But there is also a suggestion that some aircraft were flown out of Afghanistan before they could fall into the hands of insurgent fighters. Analysis of satellite images taken on 16 August from Uzbekistan's Termez airport shows more than two dozen helicopters, including MI-17, MI-25, Black Hawks and also several A-29 light-attack and C-208 aircraft, according to a Delhi-based aviation expert who did not want to be named.

Experts at security think-tank CSIS say these planes and helicopters are likely to be from the Afghan Air Force, external.

What other fighting kit has the Taliban inherited?

While there are questions over the Taliban's air power, experts agree that they have the experience to handle sophisticated guns, rifles and vehicles. And there are plenty of those in Afghanistan.

Between 2003 and 2016, the US unloaded a huge amount of military hardware on the Afghan forces it fought alongside: 358,530 rifles of different makes, more than 64,000 machine guns, 25,327 grenade launchers and 22,174 Humvees (all-terrain vehicles), according to the US Government Accountability Report.

After Nato forces ended their combat role in 2014, the Afghan army was tasked with securing the country. As it struggled to counter the Taliban, the US provided more equipment and replaced ageing military gear.

It supplied nearly 20,000 M16 rifles in 2017 alone. In subsequent years, it contributed at least 3,598 M4 rifles and 3,012 Humvees among other equipment to Afghan security forces between 2017 and 2021, according to Sigar.

The Afghan army also had mobile strike force vehicles, which it used for deployments at short notice. These 4x4 workhorses can be used to carry people or equipment.

What could the Taliban do with its new-found armoury?

That depends on the kit.

Capturing aircraft may have been easy for the Taliban, but operating and maintaining them will be difficult, says Dr Jonathan Schroden, director at the CNA consulting group and former adviser to the US forces in Afghanistan. Parts often need to be serviced and sometimes replaced, and an air force relies on a team of technicians working to maintain the airworthiness of each aircraft.

Most of the aircraft were maintained by private US contractors who had started leaving even before the Taliban assault on cities and provinces began in August.

Jodi Vittori, professor of global politics and security at Georgetown University and a US air force veteran who served in Afghanistan, agrees the Taliban lack the expertise to make these aircraft operational. "So there is no immediate danger of the Taliban using these aircraft," she says, pointing out aircraft could have been partially dismantled before the Afghan forces surrendered.

However, the Taliban will try to coerce former Afghan pilots to fly these planes, says Jason Campbell, a researcher at Rand Corporation and former director for Afghanistan in the Office of the US Secretary of Defense for Policy. "They will threaten them and their families. So, they might be able to take some of these planes to the skies, but their long-term prospects look bleak."

And the Taliban are likely to be able to operate the Russian-made MI-17s as they have been in the country for decades. For the rest, they may look to sympathetic countries for maintenance and training.

Other weaponry will be far easier for the the insurgents to get to grips with. Even Taliban foot soldiers appear to be comfortable with the ground-based equipment they have seized. Over the years, captured checkpoints and army deserters have brought them into contact with such weapons.

That the group have access to such modern weapons is a "colossal failure" says Michael Kugelman, deputy director of the Wilson Center in Washington.

But the effects will not be limited to Afghanistan. There are fears the small arms may start appearing on the black market and fuelling other insurgencies around the world.

It's not an immediate risk, says Ms Vittori, but a supply chain could appear in the coming months. The onus of stopping this is on neighbouring countries like Pakistan, China and Russia.

Mr Campbell says the Taliban appear keen to project a responsible face, although it will be hard for them not to support ideologically similar groups around the world.

Unity among the Taliban is another crucial factor which will play a part in how these weapons are used.

Ms Vittori says there is a possibility that splinter groups from within the Taliban alliance may decide to leave, taking the weapons with them. So, a lot will ride on how the leadership keeps the group together when the initial euphoria of taking over Afghanistan settles down.

Additional reporting by David Brown