Afghan robotics team: Inspirational women begin new chapter

- Published

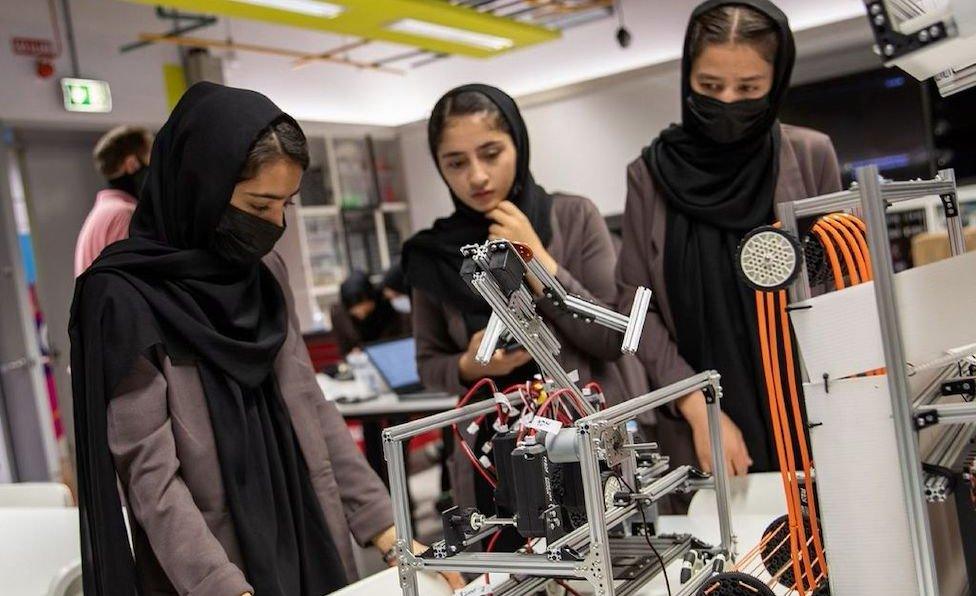

The team became a symbol for the progress of Afghan women

In a case that received global attention, a group of young scientists endured an agonising wait before they finally escaped Kabul. The BBC spoke to them about their ordeal - and why they fear for the future for Afghan women.

For 17-year-old Ayda and 18-year-old Somaya - both members of a famed, all-girls robotics team - the chaotic scenes of Kabul's fall to the Taliban will forever be etched into their memory.

"We tried to get a visa out but couldn't. We were trying to go to the airport for three days. But we couldn't. There were thousands of people trying," Ayda says of her harrowing escape from Afghanistan.

"We were in the streets and so many children were crying. They couldn't find their families."

On the third day, however, the girls managed to get on a flight organised by Qatar's government, flying to Doha alongside seven other team members, all without their families.

But even as they begin their new lives in Doha, the pair both say their minds drift back to those still in Afghanistan.

Dozens of current and former Afghan Dreamers - as the team became known - remain in the country with their families, alongside thousands of students and mentors that are part enrolled in programmes organised by the team's parent organization, the Digital Citizens Fund (DCF).

"I'm really worried about our team members, and about our coach still in Afghanistan," says Somaya, who developed an interest in technology while watching her father fix car parts in a Herat auto shop.

"But I'm also worried about all the girls in Afghanistan who want futures and careers," she adds. "It's not clear if they can continue their education or not, or whether they can pursue their dreams or not. How will their future be? Everything is uncertain."

Now, the girls - aged 15 to 19 - have set their sights on a new goal: the First Global Challenge, an Olympics-style international robotics competition that runs virtually for 12 weeks. The team members in Doha say they are already hard at work.

"We built a UVC [ultraviolet] robot that's like a sanitiser. It kills viruses, germs, and microbes from hospitals or offices," Ayda explains. "We're also going to build a CubeSat that sends information about space conditions to earth."

Fatimah Hossaini wants to use her photography to help Afghan women be seen in a different way

For the team and DCF, these sorts of competitions are nothing new.

Since being founded by Afghan tech entrepreneur and DCF founder Roya Mahboob in 2017, the team has been widely praised as a shining example of the potential of women's education in Afghanistan. The team participates in competitions around the world, with the stated aim of helping young Afghan women become interested in and developing their skills in science, technology, engineering and maths.

In 2018, then-US President Donald Trump intervened to help several team members get visas for a robotics competition in Washington DC. They've also met US senators and, this week, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken. A painting of the team even adorned one of the walls outside the now-abandoned US embassy in Kabul.

In the short term, the girls plan to remain in Doha. This week, the Qatar Foundation and Qatar Fund for Development announced that they'd be funding scholarships to finish their high school at 'Education City' in Qatar.

After that, both girls plan to apply to study artificial intelligence and robotics at university either in Qatar or abroad, before setting out on their own.

The team made headlines in 2017 by winning an international competition in the US

"I'm interested in programming. I want to build my own company that works in programming and in AI," Ayda says.

So far, the new Taliban government in Afghanistan - which has sought to present a moderate image to the international community - has said that women will be allowed to attend university.

Their studies, however, must fall within the group's interpretation of Islamic law. Many women fear a return to the way they were treated between 1996 and 2001, when harsh punishments were meted out for minor transgressions.

DCF's Roya Mahboob, for her part, says she remains hopeful for the future of the country's women.

She believes that the fact that two-thirds of the country is under the age of 25 will force the Taliban to consider that "this is a different generation to that of the 1990s".

"That's a huge number, and even the Taliban cannot ignore that," Ms Mahboob says. "Education is something that they need, and they can't deny that to girls and women…they cannot bring us back into darkness."

Ms Mahboob points to "20 years of achievements" from Afghan women. The Afghan Dreamers, she points out, have already shown their abilities, which last year included making low-cost ventilators out of car parts for Covid-19 patients.

"This is a new chapter," she says. "I know that it's going to be difficult, and challenging. But that doesn't mean we have to give up."

Looking to the future, she says the team plans to continue fighting for the rights of women in Afghanistan. In DCF's case, the group is working to bring other girls safely to Qatar to continue their education before heading further afield.

Ms Mahboob said that some team members, however, have opted to stay in Afghanistan to help with rebuilding efforts, while others haven't yet received permission from their families to leave.

A group of women protest in Kabul against the all-male Taliban government

She says that the organisation, however, can't do it alone. It's currently seeking donations and scholarship opportunities for other girls, as well as partnerships and mentors that will help them hone their technical skills.

"This could be a great opportunity for the girls. They are excited," Ms Mahboob adds. "They have a dream… we are looking forward to seeing them in the best universities in the world."

Young Ayda, for her part, directs her message directly to the international community and the Taliban alike.

"Don't leave Afghanistan. It needs your support. Children deserve a better life and to be educated," she says. "As for the new government - please let them."