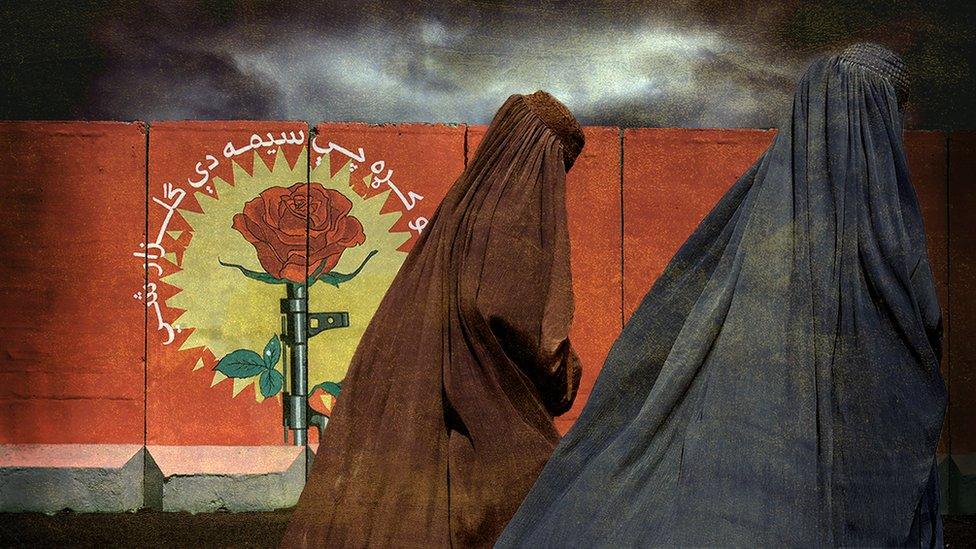

Fleeing Afghanistan: 'Women are imprisoned, while the criminals are free'

- Published

When Afghanistan fell to the Taliban, hundreds of female judges went into hiding. The Taliban had opened prisons across the country, freeing the very men the judges once incarcerated.

Twenty-six of those women have now escaped to Greece, and the BBC travelled there to meet them. For their safety, their names have been changed.

Judge Sana in her temporary accommodation in Greece. She would never stop fighting for the rights of women in Afghanistan, she said.

Close to midnight, the phone rang. With the pick-up location confirmed, it was time to leave.

Dressed in a full-length black chador, Judge Sana stepped into the street, her two young children hovering by her side. Each of them was carrying a single bag, stuffed with two sets of clothes, a passport, phone, cash, and as much food as they could carry for the journey ahead.

"When we left we didn't know where we were going," Sana recalled. "We were told there would be security risks on the way, but we accepted them all because we knew this was the only way out."

A car arrived to collect her and her children. As she climbed in, Sana looked back at the city where she had been born, raised, and begun her own family. Whether they survived was now in the hands of strangers coordinating an evacuation effort. She had no idea where they were going, but she knew they couldn't stay.

"It was the worst moment of my life, when I looked at my kids while leaving," she said. "I was so hopeless. I wondered whether I would ever get them out of Afghanistan alive."

For the past three months, Sana said, she has been hunted by the very men she sent to prison for violent crimes against women. The Taliban opened prisons as they advanced across the country, freeing thousands of criminals to take revenge on those who incarcerated them.

"I worked in a court that dealt with lots of different crimes, including murder, suicide, rape, and other complex crimes. The punishments I delivered were long and serious," Sana said.

"But after they were all released, every one of them told us: 'We will kill you if we find you.'"

Judge Sana fled Afghanistan with her two children and just four bags between them.

A recent BBC investigation found that more than 220 female judges were living in hiding because they feared retribution under Taliban rule. Speaking from secret locations inside Afghanistan, many of those women said they were receiving death threats on a daily basis.

In response to the accusations, secretary to the Taliban spokesman Bilal Karimi told the BBC: "Female judges should live like any other family without fear. No-one should threaten them. Our special military units are obliged to investigate such complaints and act if there is a violation."

Karimi also repeated the Taliban's promise of a "general amnesty" for all former government workers across Afghanistan.

But Sana described the past few months as a "living nightmare".

"We were changing locations every two to three days, moving from the street to safehouses and hotels," she said.

"We couldn't go back. Our own house had already been raided."

Evacuated

After leaving the pick-up point, Sana and her family continued the next leg of their journey overland. They travelled through the desert for more than 10 hours, she said, never sleeping. Every half an hour or so, they would arrive at a Taliban checkpoint where armed men would inspect the travellers.

Sana cradled her youngest child in her arms the entire way, she said. She didn't think they would make it out alive.

"If they knew I was a judge, they would have killed us immediately," she said, breaking down in tears. Sana had often ruled over cases where women had killed themselves due to their husband's abuse.

"I always used to think, at what point does a woman choose death? But as I began to lose hope, I reached this point. I was ready to kill myself."

After safely making it across the desert, Sana and her children spent more than a week in a safehouse, until finally they were taken to an airstrip.

As the plane took off, the entire cabin broke down in tears, she said. They were out.

The temporary apartments in Greece were simple, kitted out with bunk beds, a table and chairs.

Refuge

After arriving in Athens, all 26 judges and their family members were tested for Covid-19 before being dropped off at various apartment blocks around the city. Under a temporary visa scheme, the judges were guaranteed food and shelter by the Greek authorities, in conjunction with various charities, for 14 days.

What would happen after the two weeks were up was unknown. The judges were advised to start applying for asylum in a third country.

Among those applying for refuge in the UK was Asma. With more than 25 years' experience as a judge in Afghanistan, this was not the first time she had fled the Taliban.

In 1996, when the group seized power from the retreating Soviet army, Asma and her family fled over the border out of Afghanistan.

"This is the second time we've experienced a Taliban takeover. I was a judge when they first came to power," said Asma.

"Even then, female judges were the first to be ousted from society."

With the arrival of the US and NATO troops in 2001, Asma returned home and resumed work as a judge. Until, two months ago, history began to repeat itself.

Storm Ballos brings thunder and lightening over the Acropolis of Athens, Greece, earlier this month

Sana too had witnessed the rise of the Taliban before. She had only just graduated from law school when they swept to power in the nineties. For five years she was forced to stay home and forego work, she said.

"Becoming a female judge in itself is a huge fight," she said. "First she has to convince her own family to let her study. Then, even when she goes to university and gets a job, she still has to prove herself every step of the way.

"But female judges are needed in Afghanistan to understand the pain women are in. Like a doctor is needed to cure the sick, a female judge understands the hardships women face and she can help to solve inequality.

"For women, there is shame associated with even reporting a crime. But families are more likely to support their female relatives if there is a female judge present."

Those left behind

Pacing the walls of her tiny temporary apartment in Greece, Sana scrolled on her phone. She pointed to a picture of her old family home, a property which she said proudly was hers, by law, not her husband's.

After their evacuation, the house was commandeered by a high-ranking member of the Taliban, she said. He lives in her home, drives her car, possesses all of her belongings.

For the judges now living as a part of the diaspora, news from back home is rarely positive. In one of their many Whatsapp groups, a montage of 28 profile pictures is being shared. Every face, one judge said, was a former male prosecutor allegedly assassinated in the past 48 hours by criminals released from prison.

Sana in her Greek accommodation. Every day the authorities bring cooked food for the families to reheat and share.

Of all the women judges who made it to Greece, it was the younger ones who seemed the most broken by what they had to leave behind.

Nargis, a junior judge, served for less than five years in a provincial family court before the Taliban takeover. Her entire university and working career took place under a US-backed Afghan government.

"While the Taliban are in power it will be impossible for women to progress and to hold on to all they had achieved in the past 20 years," Nargis said.

Among the older judges, those who had witnessed not only the rise, but also the fall of the Taliban before, there was more hope.

"The women of Afghanistan are not the women of 20 years ago," said Asma. "Look at those women who protested on the first days when the Taliban arrived; asking for their rights, asking for an education.

"Even getting to this stage has not been easy. But today every daughter of our country is on her feet."

Recently arrived in Greece, Nargis looks out across the city

Sana has found her own hope too. The laws she and her fellow female judges helped forge cannot simply be deleted from history, she said. They may be ignored by the Taliban but they cannot be erased. They are searchable, sharable - a record of what was achieved.

She quoted from the constitution. Article 22: All citizens of Afghanistan, man and woman, have equal rights. Article 43: Education is the right of all citizens of Afghanistan. Article 48: Work is the right of every Afghan.

Sana had helped draft the Elimination of Violence Against Women act, which was passed into law in 2009 and made 22 acts of abuse toward women criminal offences, including rape, battery, forced marriage, preventing women from acquiring property, and prohibiting a woman or girl from going to school or work.

For now, the Taliban have decreed that all working women and female students must stay home from school or work until all workplaces and learning environments are deemed "safe". They have said it is a temporary measure, but are yet to set out a timeline for when the situation will change.

Asked whether women would hold prominent roles, such as judge or minister, in the future, Mr Karimi told the BBC he could not comment, because "the working conditions and opportunities for women" were "still being discussed".

From her new temporary shelter in Greece, Sana sees a painful injustice back home.

"Right now, women are stuck in their houses and the criminals I put away are free," she said.

She vowed she would continue to fight that injustice, even from abroad, and "support every Afghan woman".

"Afghanistan does not belong to the Taliban or any one specific group,'' she said. "It belongs to every Afghan."

Photographs by Derrick Evans.

- Published28 September 2021

- Published18 September 2021