Solomon Islands PM survives no-confidence vote after unrest

- Published

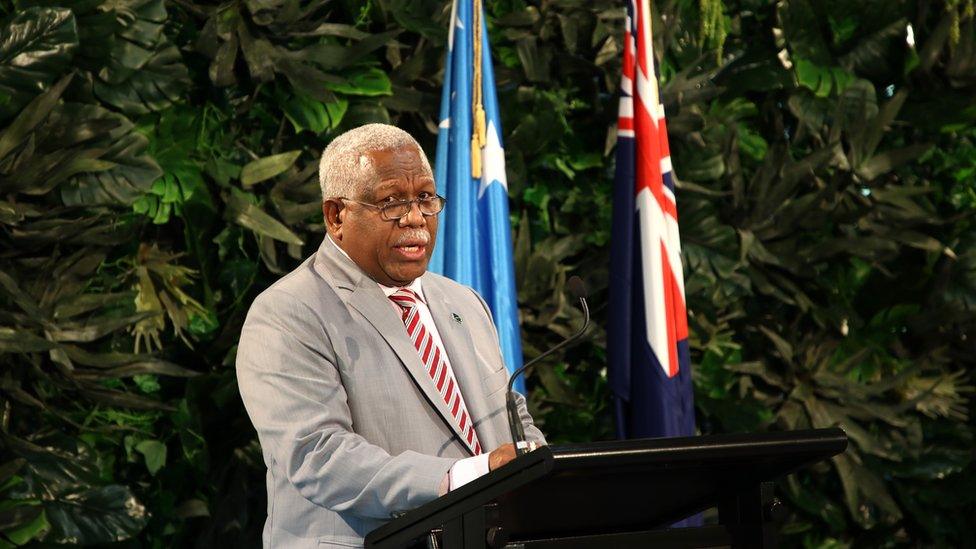

Confidence over Solomon Islands PM Manasseh Sogavare's leadership came under fire after protests broke out in the Pacific Island nation

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare survived a no-confidence vote on Monday, as lawmakers overwhelmingly voted to keep him in power.

It comes just more than a week after riots rocked the Pacific Island nation for three consecutive days.

Riots were fuelled by discontent over Mr Sogavare's decision to switch relations from Taiwan to China in 2019.

Opposition leader Matthew Wale filed the motion "in recognition of the anger on longstanding political issues".

In a parliament session on Monday, Mr Wale accused Mr Sogavare of taking money from China in an attempt to bolster his political standing, and said he was "in the service of a foreign power."

But Mr Sogavare said he switched diplomatic ties because China was an economic powerhouse, according to a Reuters report.

In the two-hour parliamentary address, Mr Sogavare said the call for him to resign was "made against the backdrop of an illegal attempted coup".

At one point, he reportedly rose to his feet and slammed his chair while screaming at Mr Wale.

The no-confidence motion eventually failed, with 15 MPs voting in support, 32 against, and two abstaining.

Why were there riots?

On November 24, protestors attempted to storm parliament and depose Mr Sogavare.

Most of the protestors were reportedly from the neighbouring island of Malaita, which had long complained of neglect from the central government in Honiara, where the protests took place.

Many pegged the unrest to Mr Sogavare's unpopular decision to switch diplomatic allegiances from China to Taiwan. The Solomon Islands had a 36-year-long relationship with Taiwan previously.

Flames rise from buildings in Honiara's Chinatown

China demands that anyone who wants to conduct diplomatic relations with it must give up formal recognition of Taiwan - a condition that has furthered Taiwan's isolation from the international community.

But why was this switch so significant?

Locally, there was a lot of "community suspicion" around how the decision was made.

There were "rumours of significant personal inducement to central government MPs to support the switch", said Mihai Sora, a Research Fellow in the Pacific Islands Program at the Lowy Institute.

"Since the switch, there has been an increased Chinese economic presence in the Solomon Islands," said Mr Sora, adding that these Chinese projects followed a pattern of awarding contracts in a "non-transparent way, employing Chinese workers and sometimes delivered to very poor quality".

For the Solomon Islands, two-way trade with China alone now makes up 46% of all trade.

But major Chinese construction projects, as well as Chinese activity in the logging industry, has also been seen as "exploitative" in nature.

"The everyday person has experienced the consequence of the switch through increased Chinese predatory economic activity in the country," said Mr Sora.

The Chinese government earlier said it was "seriously concerned about the attacks on Chinese citizens and Chinese-funded institutions," and urged the government to take all necessary precaution to protect their safety.

Is that all to it?

Not exactly. Experts say that blaming the unrest completely on the change in diplomatic relations belies deeper structural issues that plague the Solomon Islands.

At the heart of it is a long-standing divide between those in Guadalcanal - where the capital Honiara is located - and people from Malaita - the nation's most populous province but also one of its least developed.

Many Malaitans feel marginalised, and believe the government has also withheld major development projects from them.

Historically, widespread ethnic violence has broken out between both groups, from 1998 to 2003.

Separately, there are other frustrations that locals face including perceived government corruption, rapid urbanisation and a young population that faces a lack of opportunities in education and jobs.

Mr Sora says that unless structural issues are addressed - like corruption, unemployment and predatory foreign economic activity - it is unlikely that these tensions will be fundamentally addressed.

Additional contribution by BBC Monitoring's Shreyas Reddy

You might also be interested in:

Tuvalu's foreign minister discusses increasing pressure from China

Related topics

- Published13 June 2018

- Published25 November 2021

- Published21 May 2024