Afghanistan women: 'I felt anxious going back to university'

- Published

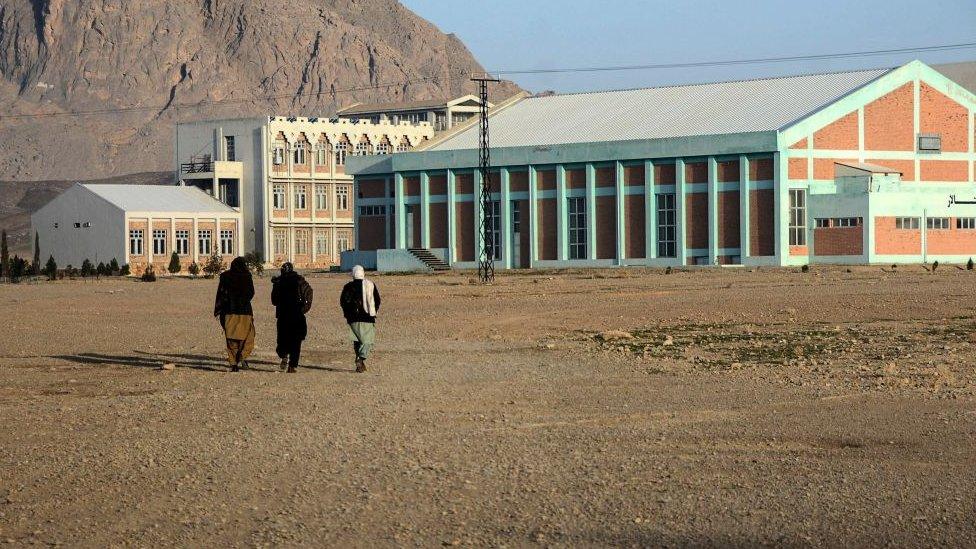

Female students walked in the courtyard of Kandahar University this week for the first time since August

Rana was worried as she got ready to return to university in Kandahar.

It had been six months since the Taliban seized power and told women to stay away from higher education and work.

On Wednesday some public universities reopened their campuses to male - and female - students after a recess. It was the first time women could attend since the takeover and a small number returned.

"I felt very anxious and the Taliban were guarding the building when we arrived, but they didn't bother us," Rana told the BBC.

"Many things felt normal, like they were before. Women and men were in the same class because our university is small - boys were sitting at the front and we were sitting at the back."

Students returned to Laghman University whilst Taliban fighters stood guard

In other universities, however, male and female students were kept apart.

One third-year student in the city of Herat told the BBC she had been told she could only be on campus four hours a day, as the rest of the time is allocated to male students.

Since sweeping to power, the Taliban have imposed strict rules on daily life, many of them against women.

Afghanistan has become the only country in the world which publicly limits education by gender - a major sticking point in the Taliban's attempts to gain international legitimacy.

Girls have been banned from receiving secondary education, the ministry for women's affairs has been disbanded, and in many cases women have not been allowed to work.

Women have also been instructed to wear the hijab, although the Taliban stopped short of imposing the burka as they did when they ruled the country in the 1990s.

A Taliban guard mans a post on the rooftop of the main gate of Laghman University

The new Taliban government says it has no objection to women's right to an education.

But education officials have said that they want classes segregated by gender and a curriculum based on Islamic principles, with wearing the hijab mandatory for female students.

'My dream was to become a doctor'

Only public universities in six of Afghanistan's warmer provinces - Laghman, Nangarhar, Kandahar, Nimroz, Farah and Helmand - resumed classes this week after the recess.

In colder areas, including the capital Kabul, higher education institutions are not expected to open their doors to male and female students until late February.

"After many months of sitting at home, this is indeed good news," says Hoda, a student who hopes to resume her civil engineering degree in Kabul. "But I know many lecturers have left Afghanistan."

BBC Pashto has established that since the Taliban took control last August, 229 professors from three of the country's major universities - Kabul, Herat and Balkh - have left the country.

For six months, 150 public universities have been closed across Afghanistan

During the Taliban's first period of rule, between 1996 and 2001, women were barred from education.

So this week's return to classes has been cautiously welcomed, however small a first step it represents.

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan tweeted: "So crucial that every young person has equal access to education."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

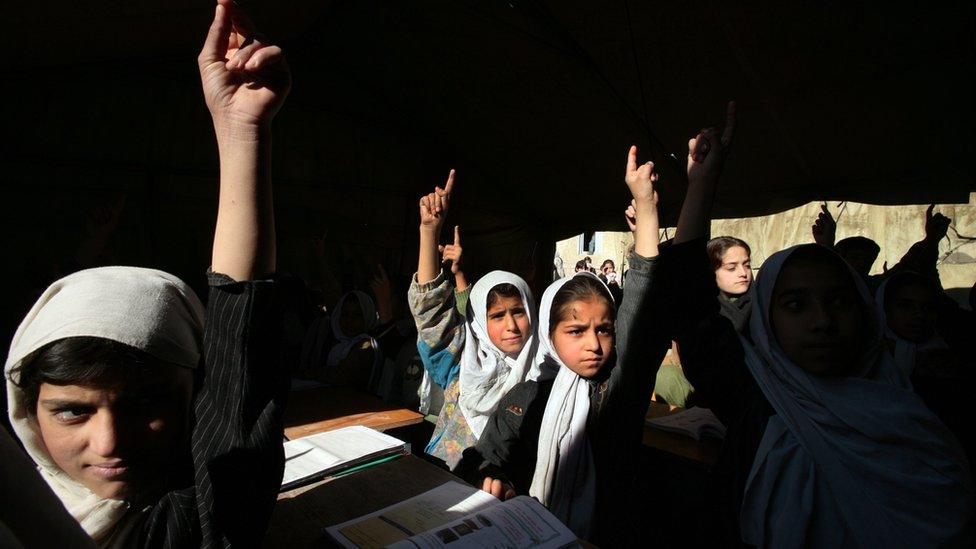

While some universities are now open for women who were enrolled before the takeover, the journey towards higher education is still very uncertain for girls.

"My dream was to go to university and become a doctor. Now that I heard the Taliban is letting women go to university, I am very hopeful that they will let us continue our education in high school and then university," says 11th-grade student Mahvash, who is 17 and from Takhar province.

'I can't really leave my home'

Some also fear that the Taliban may limit women's enrolment to a handful of courses.

A civil engineering student from Kabul said she was shocked when she recently heard a Taliban education spokesman say there was no reason for women to become politicians or engineers as these are "manly tasks".

Equally, university students who want to attend the Faculty of Arts of Kabul University told the BBC they feel uncertain as to whether the Taliban will allow women to apply for arts degrees.

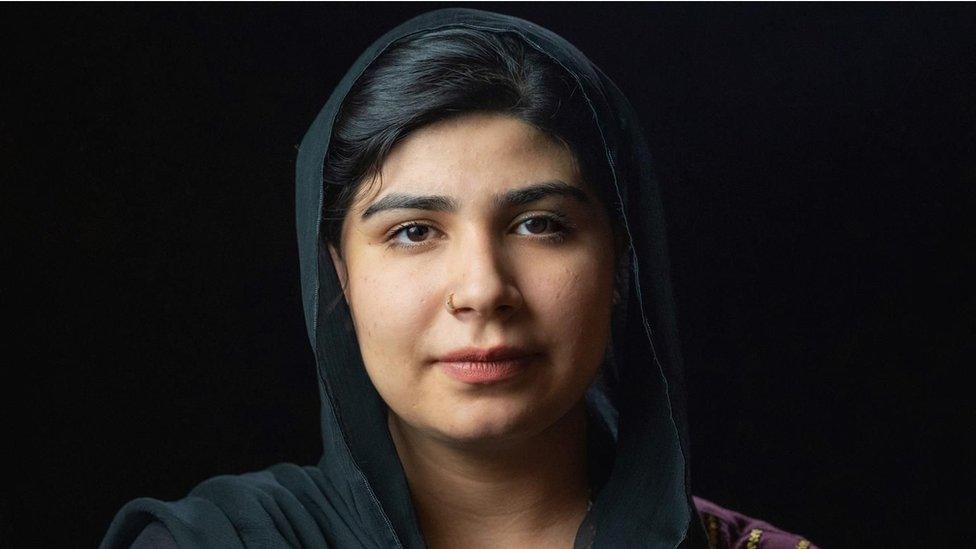

Angela Ghayour, who founded the Online Herat School to offer remote courses for women and girls, was also sceptical at the news of universities reopening.

Angela Ghayour first began teaching as a teenager to help those with no access to school

"I believe the Taliban will include more Sharia and Islamic subjects into the curriculum. The girls aren't able to play sport any more, they have to cover up more. I believe the Taliban education won't let women make their own free choices, and that is my biggest fear. I am really afraid," she said.

"As things are today, even if women graduate they cannot enter the workforce."

Soraya, a university graduate from Herat, has a degree but the current restrictions mean she cannot get a job.

"I can't really leave my home," she told the BBC. "They say women should not work, or work in an all-women environment. But there are very few work settings where you wouldn't find men."

International pressure

The reopening of public universities comes after a Taliban delegation held talks with Western officials in Norway in January, where they were pressed on improving the rights of women in order to get access to more foreign aid and the unfreezing of Afghanistan's overseas assets.

The halting of aid has worsened the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, which has already been devastated by decades of war. The UN says 95% of Afghans now do not have enough to eat.

One university student from a medical school in Mazar-e-Sharif told the BBC that "going back to university isn't a priority any more".

"We are starving. My father was working for the previous government and since the Taliban returned he is jobless and we have no food to eat, so obviously my father cannot afford my education any more. I need to buy books, clothes… but we have no money."

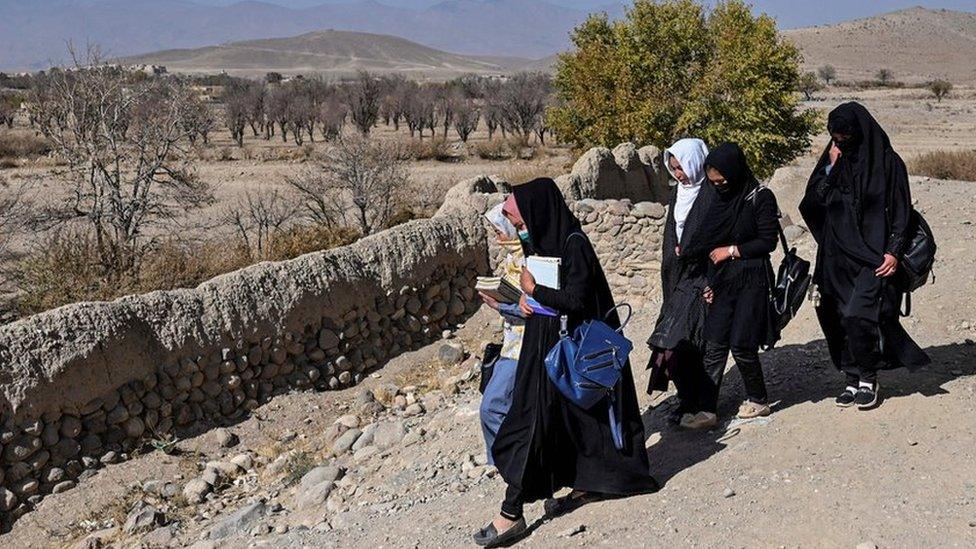

The path to higher education is uncertain for Afghanistan's schoolgirls

Others who have the means to return say they have mixed feelings about the real progress that can be achieved.

"We have lost a lot of study time and, while I'm happy that they want to reopen, there are new rules we will have to obey whilst at university. There are some things I feel uncomfortable about, such as having to have a male chaperone take me to university," says a student from Takhar who will return to lectures on 27 February.

Female students who were enrolled already may still return to classes

Pashtana Durrani, founder of Learn Afghanistan who runs schools in the country and teaches women and girls remotely, made the hard decision to leave Afghanistan for the US following the Taliban takeover.

For her, this week's news is bittersweet.

Ms Durrani, a teacher, has established schools in Kandahar

"This feels like a peace-making gesture and we need to welcome it, but as an Afghan girl who had to flee the country because my university closed down, I also feel hurt."

Ms Durrani says many of her friends who, like her, were enrolled in higher education institutions, have left Afghanistan.

"Even if they are opening universities, the country has lost so many good people."

Rana, meanwhile, wants to get back to focusing on her studies, even if she is not sure what the future holds for her and her peers.

"Many of my female classmates didn't show up [on the first day]. But here's to hoping more girls feel safer in the near future to come back to uni."

*Some names have been changed to protect the identity of the contributors.

Additional reporting by Ali Hamedani, BBC Afghan Service.

Why Afghan women fear Taliban rule

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspiring women from around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram, external, Facebook , externaland Twitter, external. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.

- Published3 February 2022

- Published24 January 2022

- Published15 December 2021

- Published12 September 2021