Pakistan's Imran Khan is fighting for his political life

- Published

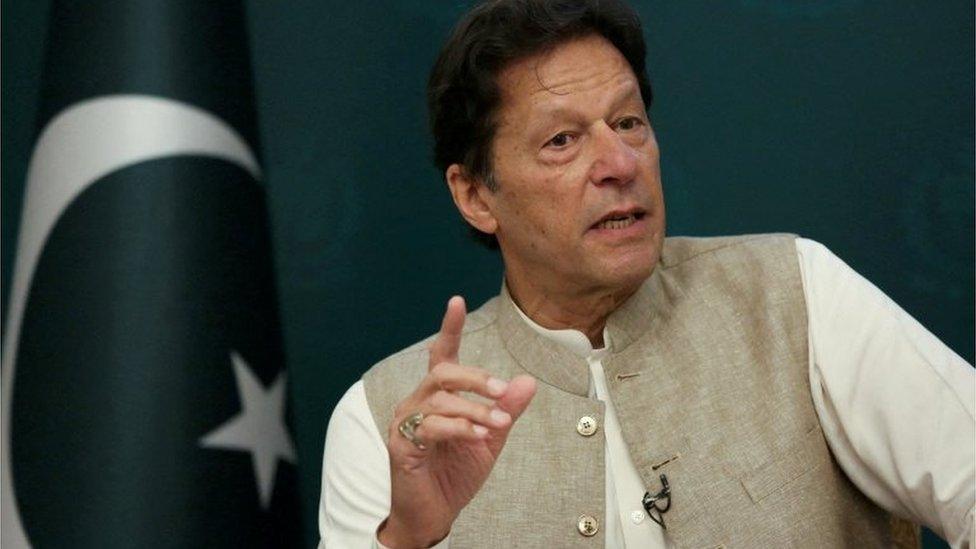

Mr Khan held a huge rally last weekend and says he's confident of winning the vote

Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan is facing arguably the biggest challenge of his political career, as the opposition seeks to remove him from office in a vote of no confidence.

The country's lawmakers have convened on Thursday to begin debating the motion as Mr Khan's future appears to be hanging by a thread. A vote is due by Monday.

In recent days there has been a flurry of activity - and what some argue were tactics straight out of Machiavelli's playbook - which resulted in several Khan allies deserting his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party, tilting the scales firmly in the opposition's favour.

A simple majority of 172 in the 342-seat National Assembly against the former cricket legend would cut short his tenure as PM. On Wednesday, the magic number was breached when his main coalition ally, the MQM, joined the opposition. It means on paper the opposition now commands 175 votes to the government's 164.

Imran Khan, elected in July 2018 vowing to tackle corruption and fix the economy, isn't going quietly. He hosted a massive rally last Sunday in Islamabad to show he remains wildly popular with his supporters.

There have been protests around the country against rising prices and inflation

Thundering against his arch-rivals - three-time premier Nawaz Sharif and Asif Zardari, husband of the murdered PM Benazir Bhutto - Mr Khan also waved a letter at the adoring crowd, alleging it contained evidence of a "foreign conspiracy" in cahoots with "corrupt thieves" aiming to topple his government.

In an address to the nation on Thursday, he alleged the conspiracy was being directed by the US, which he said was angry at his foreign policies and was working with his opponents to unseat him.

Analysts viewed the claim sceptically and the US State Department said it was not true.

Rift with the military?

Imran Khan's government does not need to look far to find its troubles. It has lost public support over rocketing inflation and ballooning foreign debt.

"For instance, from January 2020 to March 2022, India's food inflation has been about 7% whereas Pakistan's has been around 23%," explains Uzair Younus, director of the Pakistan Initiative at the Washington-based Atlantic Council.

Mr Khan was seen as the military's preferred candidate but they are reported to have fallen out

But an increasingly fractious relationship with the military - considered by many the architect of his political success, although both sides deny this - is why some analysts believe the writing is on the wall for him.

To many observers, the genesis of the current crisis can be traced back to October when Mr Khan refused to sign off on the appointment of a new chief of Pakistan's powerful ISI intelligence agency.

Analyst Arifa Noor believes that while in Pakistan conflict is "inherent" in the relationship between civilians and the military - which has directly ruled the country for almost half of its existence - the issue of replacing intelligence chief General Faiz Hameed caused a rift.

Singapore-based researcher Abdul Basit agrees, adding that the standoff was due to Mr Khan's "ego" and "rigidity" which brought an issue into the public domain which was always discussed behind closed doors.

"Imran Khan crossed the military's red line, and while he eventually accepted the appointment of the person the military wanted, it was downhill for him from then on," he says.

The military and Mr Khan deny there's been any falling out.

Third time unlucky?

There have been only two previous instances in Pakistan's political history when sitting prime ministers faced a vote of no confidence, and both times Benazir Bhutto, in 1989, and Shaukat Aziz, in 2006, emerged unscathed.

But the current parliamentary calculus clearly points towards a heavy defeat for Mr Khan, even if his own party dissidents take no part.

The government is seeking a Supreme Court ruling that would not only bar dissident PTI members from voting under an anti-defection law, but also disqualify them from parliament for life.

Meanwhile, the PM and his cabinet members are putting on a brave face, meeting allies and saying they're confident of victory.

Uzair Younus believes Imran Khan may have missed his chance to offer concessions to his allies, and even if he "miraculously manages to ride out the storm", he will be in a very precarious position.

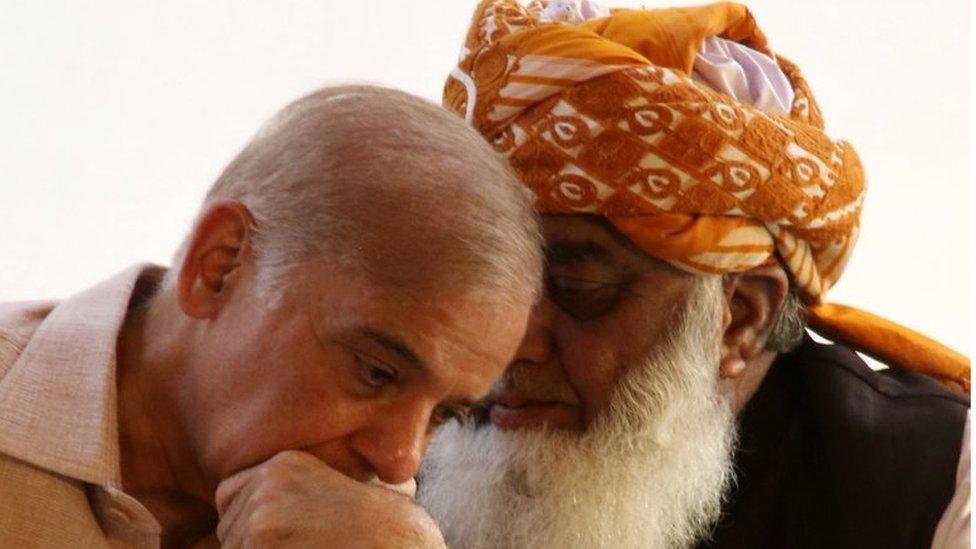

Opposition leaders have seized their chance to try to unseat the PM

"I think he must call early elections. If somehow, he survives, the longer he stays in power, the more pressure there will be on him to fix the economy," he says.

For Abdul Basit, too, the chances of Mr Khan surviving are nearly non-existent, and his prospects poor, if by a miracle he does somehow scrape through.

"Life will be terribly difficult and under current circumstances, legislation will be a nightmare, which is why I foresee elections in the next six months or so," he says.

Do the opposition have a plan?

As his rivals jostle to get rid of him, Mr Khan may feel he deserves more credit for what he's done in office.

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, the PTI did a reasonable job in providing aid to the poor, observers believe.

Pakistan's Covid statistics also bear scrutiny - a country of 220 million people recorded just 1.5 million cases and 30,000 deaths, a staggeringly low number compared with the devastation in neighbouring India last year.

Five things to know about Imran Khan (from 2018)

For analyst Arifa Noor, however, the government's signature universal healthcare programme - launched in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces - was its biggest success.

"In terms of attracting the electorate for the upcoming polls, this could be their big slogan. Some people may not have experienced Covid-related tragedy but a programme like a health card could have big ramifications for present and future," she says.

What, then, could the opposition offer, if they do manage to topple the government in a country where no prime minister has ever completed a full five-year term?

Could this hastily cobbled-together coalition provide solutions to Pakistan's deep structural, economic and societal issues?

"The opposition seems opportunistic," says Arifa Noor. "Unfortunately, in our country, because our rules of transitions are not set, every time somebody is in power, those outside think it is fair to destabilise them."

Abdul Basit believes the only plan the opposition has is to topple the government but they have not done any homework about what might happen next - nor do they appear concerned about that. "Pakistan is heading towards a prolonged period of political instability, for at least a year and a half," he says.

Uzair Younus also thinks the opposition has no plan beyond removing Imran Khan.

"They will be forced to take unpopular decisions and for which they will suffer a political cost, which will be a challenge for them," he says.

"However, no matter who wins, ultimately, the losers will be Pakistani citizens. The entire next election cycle will continue to be volatile, deeply polarising and we won't have any level of stability until after the elections."

Related topics

- Published1 February 2024

- Published26 June 2020

- Published2 June 2021

- Published15 March 2024