From handshakes to hostilities: How dangerous is the situation in North Korea?

- Published

Kim Jong-un is testing North Korea's weapons with renewed urgency, as South Korea prepares to inaugurate a new, hard-line president. After years of stalemate, following failed nuclear talks, tensions on the Korean peninsula are rising.

"I thought about getting an axe, but I decided it would be too difficult to carry, so I settled for a knife."

Sitting in a dimly-lit cocktail bar, late one night, Jenn recounts her detailed escape plan. As a South Korean, living in Seoul, she knew exactly what she would do if the North attacked. First came the weapons, then two motorbikes: one for her, the other for her brother. Their parents would ride on the back. This way they could cross the city's river quickly, before the North Koreans bombed the bridges, and hopefully make it to the coast before the port was destroyed. One evening she and her brother sat and mapped their route, agreeing to tie ribbons to the trees should they be separated.

This was five years ago. At the time, North Korea was furiously testing missiles that could, in theory, deliver nuclear bombs to the United States, and its then President Donald Trump was threatening to respond with "fire and fury". Jenn admits she was more worried than most. But nonetheless, this was the closest many South Koreans felt they had come to war since fighting with North Korea ended almost 70 years ago.

Then something remarkable happened. South Korea's newly-elected president at the time, Moon Jae-in, convinced Mr Trump to meet Kim Jong-un. It was the first time a sitting US president had ever met the leader of North Korea. A flurry of historic summits followed, sparking hope that the North might just agree to give up its nuclear weapons, and the two Koreas would make peace.

President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un briefly met at the Korean demilitarized zone (DMZ)

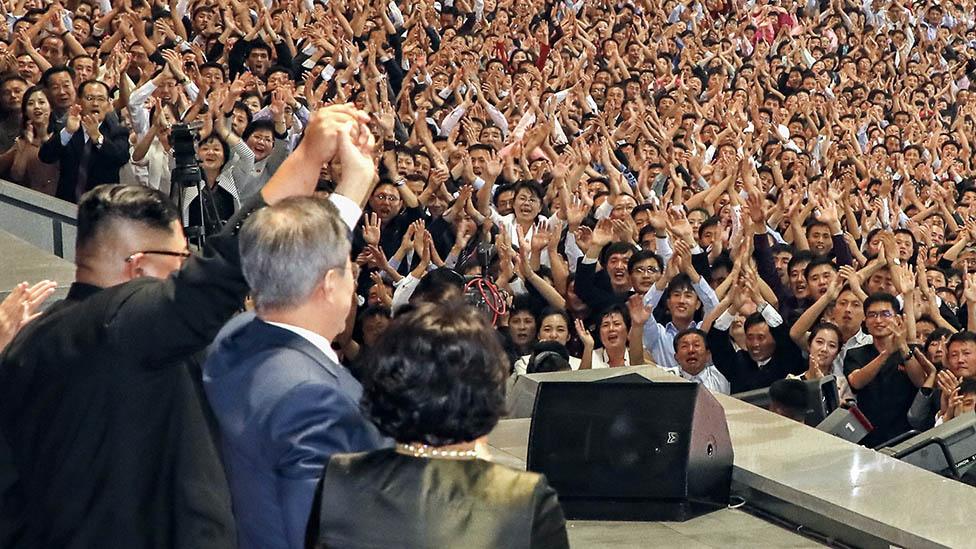

Excitement fizzed as President Moon, the son of North Korean refugees, arrived in the Capital Pyongyang and stepped out into a packed stadium, grasping the hand of his adversary. The audience didn't know what to do, recalls Prof Moon Chung-in, the president's advisor at the time. They had been told this man was their enemy, yet here he was on their soil, proposing peace. Suddenly, the 150,000 North Korean spectators erupted in raucous applause. "It was amazing to watch, it was a very moving moment for me," he says.

The North Korean crowd burst into applause after being addressed by President Moon Jae-in

But as President Moon leaves office, the hopes of that year lie in tatters. When a nuclear deal between the United States and North Korea collapsed in 2019, so did talks between the Koreas. There has been a stalemate ever since. Meanwhile North Korea has continued to develop its weapons of mass destruction and is once again testing them with alarming frequency. Only this time, the pandemic and now the war in Ukraine mean the eyes of the world have been focused elsewhere.

Asked if the government failed, Prof Moon Chung-in is defensive. "No, I don't think so! Was there war?" He reasons that for five years the Moon government kept the peace during one of the biggest crises in inter-Korean relations. It also showed what incentives would get North Korea to the negotiating table. The problem, he believes, is that North Korean negotiators returned empty-handed, in what was a great embarrassment for the regime, and almost certainly a punishable offence.

President Moon tried everything he could to coax the North Koreans back to talks, but in doing so he has been accused of appeasing one of the world's most brutal dictators.

Kim Jong-un and President Moon Jae-in met three times in 2018

"When I saw those pictures of them with their arms around each other laughing, it sent shivers down my back," remembers Hanna Song, from her office in downtown Seoul. Her organisation, the Database Centre for North Korean Human Rights, has been tracking human rights violations in North Korea for more than two decades. The last few years have not been easy.

Human rights are Kim Jong-un's Achilles' heel, Hanna explains. She says that in an effort to stop the North Korean leader from feeling uncomfortable, President Moon "swept them under the rug".

Hanna Song believes vital evidence of human rights abuses has been lost

Hanna's organisation interviews North Korean escapees at Hanawon, the resettlement centre where they live for their first three months in the country. Their testimonies play a vital role in documenting human rights abuses. But two years ago, the South Korean government cut off their access to the centre, meaning they could no longer gather their evidence. Then Hanna started hearing from escapees that they were being pressured not to speak publicly about their experiences in North Korea. Some received calls from the local policemen assigned to help them assimilate. "Are you sure it's wise to be doing this?" they asked.

Hanna tried challenging the government over the missing information. "What are you going to do when there is this gap in evidence, just because you wanted to make sure Kim Jong-un wasn't being shamed in front of the international community?" she would ask, to little response.

"What's happening in Ukraine is horrendous," Hanna concludes, "but at least we know."

Frighteningly little is known about the current situation in North Korea. Its self-imposed coronavirus border closure has stopped people, and therefore information, from leaving. What is clear is that Kim Jong-un has continued developing nuclear weapons, in spite of numerous international sanctions designed to stop him from doing so. His weapons are becoming more sophisticated and dangerous. In March, the regime tested its first intercontinental ballistic missile for the first time since the summits of 2018 began, and it flew further and for longer than any of its previously tested missiles.

Kim Jong-un pictured in front of North Korea's largest known intercontinental ballistic missile

But the hugs and handshakes are over. South Korea has elected a new, tough-talking President, a former prosecutor with no prior political experience. In a recent interview Yoon Suk-yeol described North Korea as the "main enemy" of the South and has promised to take a hard-line approach to its military escalations.

He will only talk to his neighbour, he has said, if North Korea shows it is serious about denuclearisation. But most experts now agree that North Korea has zero intention of giving up its nuclear weapons. It had reached this conclusion long before the war in Ukraine highlighted the perils of relinquishing such weapons, though this certainly has not helped. This gives Mr Yoon's strategy "zero chance of working" according to Chris Green, a consultant for the International Crisis Group, an organisation working to prevent wars.

South Korea's incoming conservative President Yoon Suk-yeol is promising to take a hard line on North Korea

During his campaign, Mr Yoon went as far as to say he would a launch a pre-emptive strike on North Korea, to destroy its weapons, if there were signs the North was about to mount an attack. This has long been part of South Korea's defence strategy, but it is rarely uttered out loud as it is a sure-fire way to enrage the North - which it did. Last month North Korea paraded its missiles through the streets, in its latest attempted show of strength. Kim Jong-un, dressed in a white military uniform, delivered a blistering warning: any hostile force that threatened North Korea, would "cease to exist". This was interpreted, at least in part, as a warning to the new South Korean president.

The North Korean leader Kim Jong-un hosting a military parade in Pyongyang in April

The North has been developing an array of short-range missiles which, for the first time last month, it hinted could be used to carry tactical nukes - the sort which could be used against South Korea in a conventional war. There are now signs it is about to test one of these nuclear bombs.

But Chris Green still believes North Korea's main goal is survival. "If it were to use a nuclear weapon, under any circumstance, it would spell the end of the regime, and North Korea knows that," he explains. Instead, Mr Green predicts an arms race between the North and South, with both building up their arsenal and testing them more frequently. These actions shouldn't lead to war, but they could lead to a miscalculation by either side. That is the biggest danger at the moment, he thinks.

Crouched around a smoking barbeque, down a back alley in Seoul, Lee Geon-il clinks glasses with his friends and they knock back their first soju of the night. "Does it taste sweet yet?" he jokes, referring to the Korean saying that the spirit turns sweet after a hard day or a hard life.

"Anything I drink at this point will be sweet," Lee Si-yeol replies. Typically, South Koreans don't pay much attention to North Korea, comforted by a belief that the United States is its real target. But Si-yeol is also about to start his compulsory military service, and as tension on the peninsula creeps up, he is struggling to shake his fear. "I know I'm unusual, but it does concern me when Kim Jong-un shoots a missile," he says. "I do worry this new hard-line policy we are adopting might provoke some sort of conflict."

Lee Si-yeol and Lee Geon-il enjoy an evening together before starting their compulsory military service

Lee Geon-il worries too. He didn't use to, he says, but the war in Ukraine has caused him to think the same could happen here. He will be an officer and admits he cannot imagine having to lead his men in an actual war. But he supports the new president. "We need to respond strongly to them saying they will use nuclear weapons, the threat is so close."

As Prof Moon Chung-in stands overlooking the presidential office, he reflects on their failed diplomacy. "The future is bleak," he concludes. "I can't see a breakthrough, not in my lifetime. We missed our opportunity."

Prof Moon Chung-in drinks soju with Kim Jong-un's sister, Kim Yo-jong, during one of the inter-Korean summits

There is unease in Seoul about what is coming, as North Korea inevitably tests the limits of the new government and tries to claw its way back up the international agenda. "I am bracing myself," a former South Korean Lieutenant General admitted, in private.

The world might be looking elsewhere, but North Korea is getting harder to ignore.