Myanmar: Air strikes have become a deadly new tactic in the civil war

- Published

Just before she left for school on the afternoon of 16 September last year, nine year-old Zin Nwe Phyo was thrilled to be given a new pair of sandals by her uncle.

She made him a cup of coffee, put on the shoes and headed off to school, a 10-minute walk away in the village of Let Yet Kone in central Myanmar. Shortly afterwards, her uncle recalls, he saw two helicopters circling over the village. Suddenly they started shooting.

Zin Nwe Phyo and her classmates had just arrived at the school and were settling down with their teachers, when someone shouted that the aircraft were coming their way.

They began running for cover, terrified and crying out for help, as rockets and ammunition struck the school.

"We did not know what to do," said one teacher, who had been inside a classroom when the air strikes began. "At first I did not hear the sound of the helicopter, I heard the bullets and bombs hitting the school grounds."

"Children inside the main school building were hit by the weapons and began running outside, trying to hide," said another teacher. With her class she managed to hide behind a big tamarind tree.

"They fired right through the school walls, hitting the children," said one eyewitness. "Pieces flying out of the main building injured children in the next building. There were big holes blown out of the ground floor."

Belongings on the floor of a classroom after the air strike

Their attackers were two Russian-made Mi-35 helicopter gunships, nicknamed "flying tanks" or "crocodiles" because of their sinister appearance and protective armour. They carry a formidable array of weapons, including powerful rapid-fire cannon, and pods that fire multiple rockets, which are devastating to people, vehicles and all but the strongest buildings.

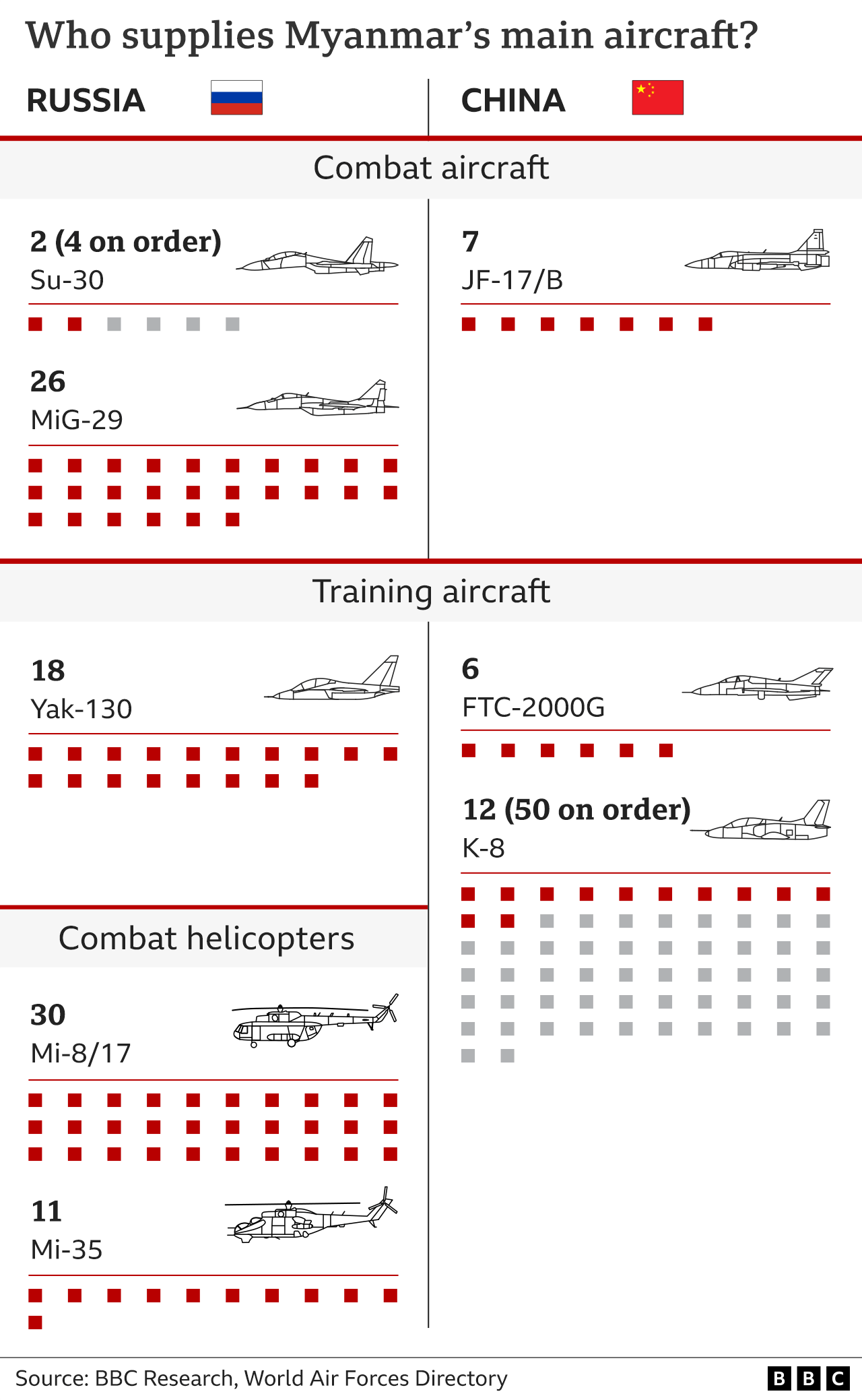

In the two years since Myanmar's military ousted Aung San Suu Kyi's elected government, air strikes like this have become a new and deadly tactic in a civil war that is now a brutal stalemate across much of the country, conducted by an air force which has in recent years grown to about 70 aircraft, mostly Russian and Chinese-made.

It's hard to estimate how many have died in such air attacks because access to much of Myanmar is now impossible, making the conflict's true toll largely invisible to the outside world. The BBC spoke to eyewitnesses, villagers and families over a series of phone calls to find out how the attack on the school unfolded.

The firing continued for around 30 minutes, eyewitnesses said, tearing chunks out of the walls and roofs.

Then soldiers, who had landed in two other helicopters nearby, marched in, some still shooting, and ordered the survivors to come out and squat on the ground. They were warned not to look up, or they would be killed. The soldiers began questioning them about the presence of any opposition forces in the village.

Zin Nwe Phyo, 9 (L) and Su Yati Hlaing, 7

Inside the main school building three children lay dead. One was Zin Nwe Phyo. Another was seven-year-old Su Yati Hlaing - she and her older sister were being brought up by their grandmother. Their parents, like so many in this region, had moved to Thailand to seek work. Others were horribly injured, some missing limbs. Among them was Phone Tay Za, also seven years old, crying out in pain.

The soldiers used plastic bin liners to collect body parts. At least 12 wounded children and teachers were loaded on to two trucks commandeered by the military and driven away to the nearest hospital in the town of Ye-U. Two of the children later died. In the fields skirting the village, a teenage boy and six adults had been shot dead by the soldiers.

This is a country that has long been at war with itself. The Burmese armed forces have been fighting various insurgent groups since independence in 1948. But these conflicts were low-tech affairs, involving mainly ground troops in an endless tussle for territory in contested border regions. They were often little different from the trench warfare of a century ago.

It was in 2012 in Kachin state - just after the air force had obtained its first Mi-35 gunship - that the military first used aerial weapons extensively against insurgents. Air strikes were also used in some of the other internal conflicts which kept burning throughout Myanmar's 10-year democratic interlude, in Shan and Rakhine states.

However, since the February 2021 coup, the army has suffered heavy casualties in road ambushes carried out by the hundreds of so-called People's Defence Forces, or PDFs - volunteer militias that were established after the junta crushed peaceful protests against the coup.

So it has relied on air support - bombing by aircraft suitable for ground attack; or air mobile operations like the one at Let Yet Kone, where gunships blast targets before soldiers arrive to kill or capture any opposition forces they find.

Your device may not support this visualisation

There were at least 600 air attacks by the military between February 2021 and January 2023, according to a BBC analysis of data from the conflict-monitoring group Acled (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project).

Casualties from these strikes are difficult to estimate. According to the clandestine National Unity Government or NUG, which leads opposition to the military regime, air attacks by the armed forces killed 155 civilians between October 2021 and September 2022.

The resistance groups are poorly armed, with no capacity to fight back against the air strikes. They have adapted consumer drones to launch their own air attacks, dropping small explosives on military vehicles and guard posts, but to limited effect.

It is not clear why Let Yet Kone was targeted by the army. It is a poor village of around 3,000 inhabitants, most of them rice or groundnut farmers, set in the scrubby brown landscape of central Myanmar's dry zone, where water is scarce outside of the monsoon season.

It is in a district called Depayin where resistance to the coup has been strong. Depayin has seen many armed clashes between the army and PDFs, although not, according to residents, in Let Yet Kone. At least 112 of the 268 attacks recorded by the NUG were in southern Sagaing, where Depayin is located.

A spokesman for the military government said after the school attack that soldiers had gone to the village to check the reported presence of fighters from a PDF and from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), and that they had come under fire from the school. This account is contradicted by every eyewitness who spoke to the BBC. The military has produced no evidence of insurgent activity at the school.

The school had been set up only three months earlier in the Buddhist monastery at the northern edge of the village. It taught around 240 pupils. Residents told the BBC that it is one of more than 100 schools in Depayin which are now being run by communities opposing military rule.

Teachers and health workers were among the earliest supporters of the civil disobedience movement. In one of the first and most widely-supported acts of defiance against the coup, state workers vowed to withdraw all co-operation with the new military government. As a result a lot of schools and health centres are now being run by communities, not the government.

Phone Tay Za's mother says she heard the shooting and explosions start about 30 minutes after she had seen her son off to school. But, like Zin Nwe Phyo's uncle, she assumed it could not be the target of the helicopter gunships.

"After the sound of the heavy guns firing died down I headed toward the school," she said. "I saw children and adults squatting on the ground with their heads lowered. The soldiers were kicking those who turned their heads up."

She begged the soldiers to let her look for her son. They refused. "You people care when your own get shot," one told her, "but not when it happens to us."

Then she heard Phone Tay Za calling out to her, and they let her go to him inside the ruined classroom.

"I found him in a pool of blood with eyes blinking slowly. He said, 'mom, just kill me please.' I told him he would be fine. 'You will not die'."

"I cried my heart out, shouting 'how dare you do this to my son'. The whole monastery compound was in absolute silence. When I shouted, it echoed through the buildings. A soldier yelled at me not to scream like that and told me to stay still where I was. So I sat there in the classroom for about 45 minutes with my child in my arms. I saw three children's dead bodies there. I did not know whose children they were. I could not look at their faces."

Phone Tay Za died shortly afterwards. The soldiers refused to let his mother keep his body and took it away. The bodies of Zin Nwe Phyo and Su Yati Hlaing were also taken by the military, before their families could see them, and later secretly cremated.

A thousand kilometres away in Thailand Su Yati Hlaing's parents were working their shifts in the electronic components factory when they heard that the military had attacked their village.

Su Yati Hlaing's parents were working in Thailand in the hope of earning enough to give her a better life

"My wife and I were in agony. We could not concentrate on our work anymore," her father said.

"It was around 2:30 in the afternoon so we could not leave. We kept working, with heavy hearts. Colleagues asked us if we were ok. My wife could not hold her tears anymore and started crying. We decided to not do the usual overtime that day and asked our team leader to go back to our room."

Later that evening they got a call from Su Yati Hlaing's grandmother telling them she had been killed.

The attack in Let Yet Kone drew international rebuke and horror, but the air strikes continued.

On 23 October air force jets bombed a concert in Kachin State commemorating the anniversary of the start of the KIA insurgency.

Survivors say three huge explosions ripped through the large crowd which had gathered for the event, killing 60 people, including senior KIA commanders and a popular Kachin singer. Many more are thought to have died in the following days after the army blocked the evacuation of those who had been seriously injured in the attack.

PDFs or volunteer militias have inflicted heavy casualties on the Burmese forces

At the other end of the country the air force bombed a lead mine in southern Karen State, close to the border with Thailand, on 15 November, killing three miners and injuring eight others. The junta spokesman justified the attack on the grounds that the mining was illegal, and in an area controlled by the insurgent Karen National Union.

And only last month, the air force bombed the main base of the insurgent Chin National Front, next to the border with India. It also launched air strikes which hit two churches in Karen State, killing five non-combatants.

This increased capacity for aerial warfare is being sustained by continued support from Russia and China after the coup, despite many other governments ostracising Myanmar's military regime.

Russia, in particular, has stepped up to become its strongest foreign backer. Russian equipment, like the Mi-35 and the agile Yak-130 ground attack jets, are central to the air campaign against insurgents. China has recently supplied Myanmar with modern FTC-2000 trainers, aircraft which are also well-suited for a ground attack.

The high death toll in such attacks has drawn the attention of war crimes investigators. The Myanmar armed forces have often been accused of such crimes in the past - often abuses by ground troops, particularly against the Rohingyas in 2017. But the use of air power brings with it new types of atrocities.

For the survivors of Let Yet Kone, the nightmare did not end on 16 September.

They say many of the children and some of the adults are still traumatised by what they saw that day. The military has continued to target their village, attacking it again three more times, and burning down many of the houses.

This is a poor community. They do not have the resources to rebuild, and in any case they do not know when the soldiers will be back to burn them again.

"Children are everything for their parents," says one local militia leader. "By killing our children, the military has crushed them mentally. And I must say they have succeeded. Even for me, I will need a lot of motivation to carry on the revolutionary fight now."

Su Yati Hlaing's parents are still in Thailand, unable to return after their daughter's death. They cannot afford the cost of the journey, nor the risk of losing the factory jobs they had always hoped would give their little girl a better life.

"There were many things I had imagined," says her mother. "I imagined that when I finally went back I would live happily with my daughters, I would cook for them, whatever they wanted. I had so many dreams. I wanted them to be wise and educated, as much as we, their parents, are uneducated. They were just about to begin their journey. My daughter did not even get our affection and warmth closely, because we were away so long. Now, she is gone for forever."

The BBC analysed attack data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (Acled), which collects reports of incidents related to political violence and protests around the world. Aerial attacks have been defined as conflict events involving aircraft in specific locations either during an armed clash or as an independent strike. The data covers the period 1 February 2021 to 20 January 2023.

Additional reporting: BBC Burmese

Data analysis: Becky Dale

Production: Lulu Luo, Dominic Bailey

Design: Lilly Huynh

Related topics

- Published1 February 2021

- Published15 July 2022

- Published16 January 2023

- Published1 February 2021

- Published1 February 2022