Yellow dust: Sandstorms bring misery from China to South Korea

- Published

From his high rise office window, Erling Thompson watches the Seoul skyline fade into a yellow-grey cloud as fine dust from sandstorms in China blankets South Korea.

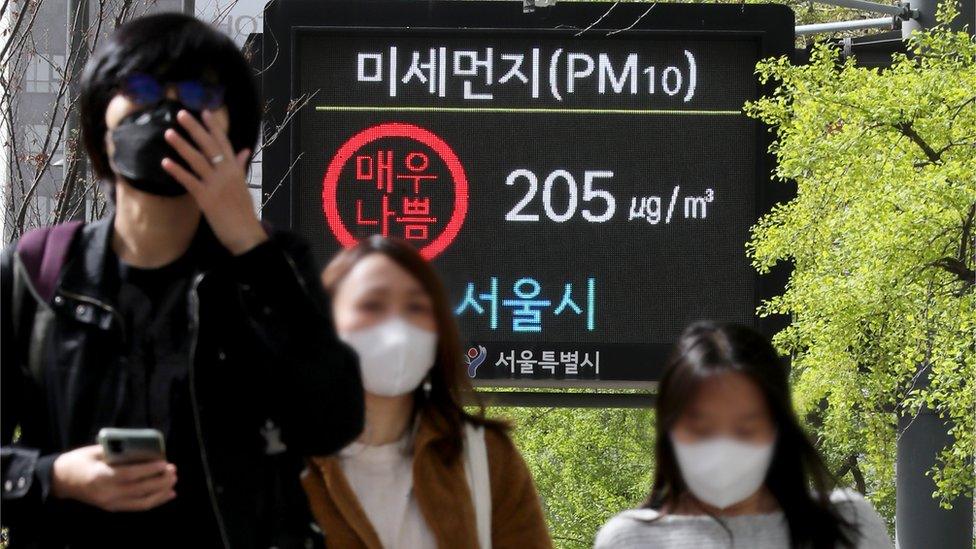

On the streets below, people wear face masks and hooded jackets to ride out another dust-covered day that is no less miserable and unhealthy, even if it is expected at this time of the year.

Yellow dust is a seasonal ordeal for millions in North Asia, as sandstorms from the Gobi desert that borders China and Mongolia ride springtime winds to reach the Korean peninsula and this year, farther east to Japan.

It aggravates air pollution and puts people at greater risk of respiratory disease as the particles are small enough to be inhaled into the lungs.

"You don't feel happy. It's like a very bad weather day. You naturally want to be outside on a sunny day. But when the weather is very dirty, you feel depressed and want to stay inside," said the 34-year-old Thompson, who moved from the US to South Korea in 2011 for work.

Eom Hyeojung said there appears to be "no realistic way to avoid yellow dust", so she sent her daughter to school anyway despite the health risks.

"As it happens so often, like every year, I just let her go. It's sad, but I think it became just a part of our life," said the 40-year-old teacher from Seoul.

Han Junghee, a 63-year-old telemarketer, said the sky appeared to be getting murkier by the day so she has been avoiding exercise outdoors.

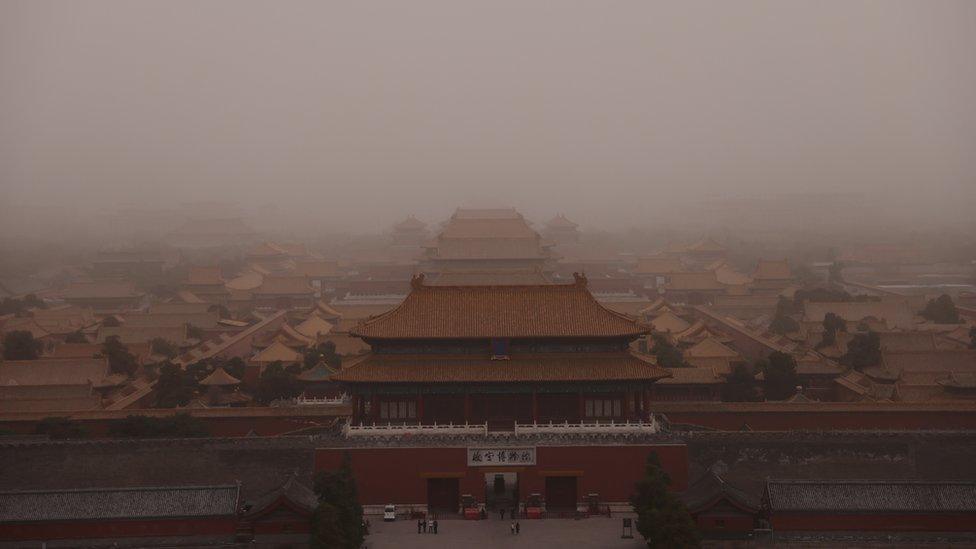

The expanse of Beijing's Forbidden City fades into a dust cloud in early April

Motorists drive through an evening sandstorm in Beijing this week

Sandstorms in the region have been increasing in frequency since the 1960s due to rising temperatures and lower precipitation in the Gobi wilderness, Chinese authorities said.

This year, sandstorms started bearing down on parts of China in March, causing the skies to turn yellow. In the first two weeks of April alone, there have been four sandstorm and the most recent one left cars, bikes and houses coated in dust.

On Chinese social media platform Weibo, a video of a woman sweeping three kilos of dust inside her apartment in Inner Mongolia has gotten three million views. She accidentally left a window open during the sandstorm.

A 31-year-old woman in Beijing who doesn't want to be named said she was covered in dust "like a terra cotta warrior" after a brief run outside her house.

"Even my bedroom smells like dirt when I go to sleep. We've been quite used to sandstorm weather here in Beijing because it happens every spring. But the wind is too strong this time. I was the unlucky one," she said.

Shanghai's Jin Mao Tower and World Financial Centre are barely visible due to a sandstorm on 11 April

The sandstorms originate from the Gobi desert that borders China and Mongolia

A sandstorm on 11 April reduced the towering buildings in Shanghai's Pudong district to mere outlines in the night sky. Twelve provinces were placed under a sandstorm warning the following day.

A Shanghai resident said the morning after a sandstorm meant the additional chore of washing down her bike before she could use it. The 30-year-old woman said she wondered how the time bought by more than two years of COVID restrictions failed to produce measures to mitigate the effects of the seasonal sand storms.

At the height of the most recent sandstorm, the concentration of fine dust or PM 10 in the Chinese capital was 46.2 times the World Health Organization's guideline value.

In Seoul, PM 10 levels were double the government threshold to qualify as very bad for health. In the city of Ulsan, southeast of the capital, it was even higher.

The health risk from PM 10 particles is immediate as they are easily inhaled. One particle is smaller in diameter than human hair.

South Koreans have been advised to mask up as yellow dust blankets the country

Dust from sandstorms is a seasonal problem for South Korea, as shown in this photo taken in Seoul in 2021

As China and South Korea grapple with yellow dust from sandstorms, Thailand, south of the continent, is dealing with its own pollution problem as wildfires and the burning of sugarcane fields blanket the country's northern region in smog.

Among the hardest hit is tourist favourite Chiang Mai, where golden temples and lush greenery has been shrouded in thick smoke for weeks.

On the week yellow dust blanketed large parts of northeast Asia, Chiang Mai took the dubious distinction of being the world's most polluted city.

A jet made a haze-covered descent over Chiang Mai Thailand in March

Related topics

- Published30 March 2023

- Published16 May 2022

- Published15 March 2021

- Published22 November 2018