Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo: I have no enemies

- Published

Liu Xiaobo's work is more available abroad than in his home country

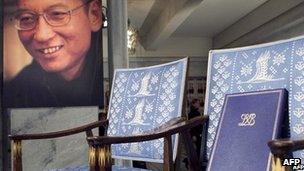

A book containing the thoughts of last year's Nobel Peace Prize winner has been published in English on the first anniversary of his award.

The publication - called No Enemies, No Hatred - is a collection of essays and poems written by the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo.

He is currently serving an 11-year prison sentence in north-east China for helping draft a manifesto calling for political change.

His book comes at a time when many believe human rights in China are being eroded by a government fearful of change.

'No censorship'

The activist wrote about a range of subjects; the Beijing Olympics, Chinese rule in Tibet and the modern enthusiasm for Confucius, the ancient Chinese thinker.

All these topics are covered in the book, which is being published in English by Harvard University Press. The Chinese version came out last year.

The title comes from a statement Liu Xiaobo prepared before his brief trial for inciting subversion in December 2009.

In that statement he reiterated a belief he first expressed 20 years ago - that he has no enemies and no hatred.

"None of the police who monitored, arrested and interrogated me, none of the prosecutors who indicted me, and none of the judges who judged me are my enemies," wrote the dissident.

The book has been edited by Perry Link, an American friend of the author who now works at the University of California, Riverside.

He said it was Liu Xiaobo's honesty that made him different from other Chinese activists and dissidents.

"He made a decision a few years ago to say whatever he thought without any censorship," said Mr Link, who has published numerous books on China.

"Until I read his essays carefully while editing this book, I didn't realise how insightful he was on China."

That view is shared by another of the book's editors, Liao Tienchi, who was born in Taiwan, but now lives in Germany.

"He is a brilliant analyst of China's situation. He writes his thoughts in very clear language," said Ms Liao, president of the Independent Chinese Pen, a human rights organisation.

But she said he had a less clear understanding of the outside world, mainly because he cannot read English well.

"He's not that critical about the American view of the world," she said.

Liu Xiaobo would probably have remained a little-known intellectual had he not be given the peace prize, which he won mainly because he had become a symbol of the fight for rights in China.

He was sent to prison just as the Nobel committee were looking to honour a Chinese dissident.

The government in Beijing was furious when the award was announced, repeating its belief that Liu Xiaobo was simply a criminal who incited subversion when he helped write Charter '08.

The dissident's work, which in this book spans 20 years, remains largely unknown in his own country. He remains in prison.

- Published7 October 2011

- Published10 December 2010

- Published10 December 2010

- Published10 December 2010