Poor rural villages show China's economic dilemma

- Published

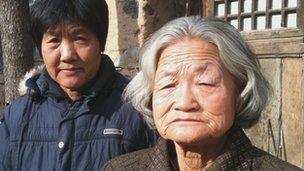

Liu Wenxiang (l) and her mother say they get little help from the government

The debt problems in Europe have led many to hope that China will use its financial muscle to save the world. But China has its own pressing economic problems, as Michael Bristow finds out.

China's remarkable economic development is reflected in its booming cities of skyscrapers, expensive cars and designer clothes shops.

Few foreign visitors travelling to Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou fail to be impressed by the country's recent achievements.

But there is another side of China that is less visible - the poor rural areas that suggest growth has been uneven, or worse, has left some behind.

China has the world's second-biggest economy but, because of its 1.3bn people, it has a per-capita income on a par with countries such as Tunisia and Angola.

Just three hours drive from Beijing is the village of Yihezhuang - where nearly 300 people have an average income of less than 1,000 yuan ($157, £101) a year.

China's leaders are under political pressure to provide these people with basic services before helping out richer Western nations.

Wartime base

It is not easy to get to Yihezhuang, which has been built in the mountains that run along the border between Beijing and Hebei province.

There is just a basic track running about 7km (4 miles) from the main road to the village. Some homes can be reached only on foot.

Its isolated location - and its proximity to Beijing - is probably why the communists chose this place as a base to fight the Japanese in World War II.

Older residents still remember treating wounded soldiers.

The village was poor then and there is not much to suggest it has benefited from China's rapid economic growth over the last few decades.

Villagers in Yihezhuang eke out a meagre living by growing maize and raising animals

People live in dilapidated courtyard homes, where the only source of heating is a large bed warmed by a smoky fire underneath.

This is how most rural houses are heated in northern China, where temperatures regularly drop below freezing in winter.

"We don't get any subsidies from the government," said villager Liu Wenxiang, 54.

"We were enrolled in a pension scheme earlier this year, but we won't receive any money until we're 60. My mother's nearly 80 and she isn't covered at all."

One way in which China can help the world's economy is by persuading its people to buy more foreign products.

But in the home belonging to Mrs Liu's parents there is little that a Westerner would recognise as a consumer product.

A chipped teapot on a small table, a broken-down sideboard and an earthenware pot filled with water are the most obvious items in its main room.

It is going to be a long time before this family can afford expensive kitchen appliances or computer gadgets.

Escaping poverty

Liu Wenxiang's father has lung cancer and spends most of his time sitting on the heated bed, bundled up in multiple layers of clothing.

The family say they do not have enough money to give him proper treatment. "What can we do?" said the sick man's wife.

Villagers hope to turn their mountain homes into tourist attractions

China's government is in the process of introducing health insurance across the country, but coverage is patchy.

Yihezhuang's residents recently joined this scheme, but getting back money spent on health care is not easy, they say.

As in many Chinese villages, there are few young adults. Most have gone away to seek work in the towns and cities.

Those who are left eke out a living growing maize and vegetables - most of which is kept by households for their own consumption. Others keep goats, pigs and chickens.

The situation in the village is extreme - a fact acknowledged by provincial leaders, who visited in October to see what could be done to help.

"We must do all we can to help impoverished areas and villagers find projects and industries that allow them to escape poverty," said Shen Xiaoping, Hebei's deputy governor.

But there are thousands of villages like this one across China, whose rural people have not benefited as much as city dwellers from economic growth.

In urban areas, the average disposable income was 19,109 yuan ($2,990, £1,930) last year. It was less than a third of that in the countryside.

Independent economist Andy Xie said China should help these people by cutting their tax burden, and improving welfare and education provision.

That takes precedence over helping others. "Why would we rescue Greece? Does it buy from us or sell to China?" said the economist.

Change is already coming to Yihezhuang. The dirt path that once linked the village with the outside world - and was often washed away by floodwater - has now been replaced by a government-funded stone road.

The authorities plan to pave it properly in the next few years.

When than happens, village accountant Liu Dianshan said, people will turn their poor but picturesque homes into tourist destinations.

"Visitors will be able to stay in farmers' homes and we'll be able to move people to more convenient parts of the village," said a hopeful Mr Liu.

That might take some years, but China's leaders know that fulfilling these dreams - and others like them - is more important than sorting out foreign debt problems.

- Published28 November 2011

- Published27 November 2011

- Published24 November 2011