Inside Tibet

- Published

The world has long been fascinated with Tibet

The world has long been fascinated with Tibet

Tibet has long captured the West's imagination as the site of a mystical Utopia.

Geographically dramatic and remote, it has an average altitude of 13,000ft (4,000m) above sea level and is popularly referred to as "the roof of the world".

It is isolated not only geographically, but also diplomatically. China enforced a long-held claim to Tibet in 1950, and it was subsequently incorporated into Chinese territory.

Tibet's spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, fled to Dharamsala in northern India, where his supporters have set up a government in exile. Meanwhile Tibet itself is rapidly changing, as increasing numbers of Han Chinese arrive in search of work.

The Dalai Lama talks with Chinese leader Mao Zedong in 1956

The Dalai Lama talks with Chinese leader Mao Zedong in 1956 Protests against Chinese rule by Tibetan monks

Protests against Chinese rule by Tibetan monks

During Tibet's early history it was an independent and often powerful state, but from the 13th century, when it submitted to Mongol rule, until modern times, it has endured long periods of either Chinese control, Chinese influence, or effective autonomy.

In 1904 British Colonel Francis Younghusband led a mission to seize Lhasa and attempt to exclude other foreign powers' influence over Tibet.

But in 1907 Britain and Russia agreed that both parties would deal with Tibet only through China, and China enforced what it saw as its claim on Tibet through a military invasion in 1910.

It withdrew in the midst of a Chinese revolution in 1911, and to all practical purposes Tibet operated as an independent nation from then until the early 1940s.

This was to change dramatically in 1949, when communist Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China and threatened Tibet with 'liberation'.

China led a military assault on Tibet in October 1950, and in April 1951 Tibet's leaders said they were strong-armed into signing a treaty, known as the 'Seventeen Point Agreement', which gave China control over Tibet's external affairs and allowed Chinese military occupation, in return for pledging to safeguard Tibet's political system.

There was widespread open rebellion against Chinese rule within Tibet by 1956, which tipped over into a full uprising in March 1959. Tibetans say that thousands died during the occupation and uprising, but China disputes this.

On the night of 17 March the Dalai Lama fled to northern India. Some 80,000 Tibetans followed over the next few months.

The Chinese government went on to establish the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) in 1965, and in 1966 Tibet was subjected to China's Cultural Revolution, which destroyed a large number of its monasteries and cultural artefacts.

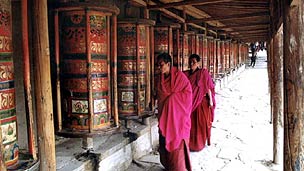

Since the 1980s, Tibet has enjoyed mixed fortunes. People's freedom to practise their religion has been restored, though monks and nuns still often face persecution. But large-scale Han Chinese immigration, Tibetans say, threatens their unique culture.

In March 2008, tensions between the Tibetan and Han Chinese communities in Lhasa erupted into deadly violence. Clashes spread to provinces bordering Tibet and lasted for several days.

Many Tibetans used to be nomadic herders

Many Tibetans used to be nomadic herders

Tibet's physical isolation means that it is home to some unique animal and plant species. But its rapid development and resettling by the Han Chinese mean its special environment is now under threat.

Tibet is about 70% grassland, and its main economy is agricultural. Human rights groups say that the Chinese government's policy of settling the region's nomads is having a substantial impact on Tibet's ecology.

The stated aims of the government's policy are to improve the economic viability of farming and protect the nomads from natural disasters. While this has led to some short-term gains, Tibetan groups say, it has led to the over-grazing of some grasslands. Tibet's wildlife is also at risk from widespread commercial hunting and poaching.

Environmental groups say pressure on Tibet's resources increased with the opening of a controversial rail link from Golmud in Qinghai province to Lhasa in 2006. According to the Tibetan government in exile, the railway cuts through three nature reserves, all home to endangered antelope and gazelle.

China believes Tibet to be an important reservoir of natural resources. It is the prime source of Asia's major rivers, and harbours extensive forest and minerals.

The Dalai Lama has been in exile since 1959

The Dalai Lama has been in exile since 1959

Buddhism, which arrived in Tibet from India, became the region's state religion in the 7th century, and has since played a paramount role. Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer, who lived in Tibet in the 1940s, said: 'In all my years in Tibet, I never met anyone who expressed the slightest doubt about Lord Buddha's teaching.'

But religion has become, by necessity, politicised in modern Tibet, as communist China is suspicious of fervent worship. China also sees the Dalai Lama - the leading spiritual figure of the Tibetan people - as a separatist threat.

The Dalai Lama, or Ocean of Wisdom, is seen as the embodiment of compassion. When a Dalai Lama dies, the search for his next incarnation begins. He is identified by his ability to pick out articles belonging to the previous one.

The current, 14th Dalai Lama, has lived in exile in northern India since the Chinese invasion in 1959. The Panchen Lama, the second most important figure in Tibet's spiritual hierarchy, is presently controversial because China and Tibet disagree over his current incarnation.

The Dalai Lama identified him to be a boy called Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, but the Chinese detained him in 1995 and he has not been seen since. The Chinese then installed their own choice, Gyaincain Norbu, who has been rejected by the Tibetans.

Chinese and Tibetan views of what constitutes Tibet differ significantly.

Around half the landmass the Tibetans consider to be Tibet has been subsumed into other Chinese provinces, and in 1965 the Chinese government named the rest the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR).

The government says the TAR has considerable autonomy, but many Tibetans argue their self-government exists in name only.

The Chinese government has been encouraging mass Han Chinese migration into Tibet, which it says is helping the region improve economically.

According to Chinese government statistics, Tibet's GDP in 2003 was about 28 times what it was in 1978. Regional officials say they achieved double-digit growth in 2011.

Aside from agriculture, tourism is now becoming a major industry in the region. Authorities said Tibet received 8.5m tourists in 2011, a rise of 33% on 2010. Tourist sector income also grew 24.1% in 2011 to 9.5bn yuan ($1.5bn, �956bn).

As of May 2011, Tibet had three million permanent residents, up 14.75% from the census in 2000. According to Tibet's regional bureau of statistics, the population grew at a rate of 1.4%, compared to the national average of 0.57%. China's one-child policy does not cover the region.

Tibetans now comprise 90.48% of the population, Han Chinese make up 8.17% and other population groups 1.35%. But Tibetans say that the Han Chinese have a disproportionate influence, dominating the region's economy and threatening its cultural identity.

The controversial $4.2bn, high-altitude Qinghai-Tibet railway continues to ferry passengers and workers between Beijing and Lhasa.

China says that its policy of investing in the region will benefit Tibetans and raise them out of poverty. "The Tibet Autonomous Region would continue to follow the opening-up policy for the sake of its own development," Premier Wen Jiabao has said.

But the Dalai Lama has warned of a "cultural genocide" and religious repression in the region, linking sporadic unrest in and around Tibet with these issues.