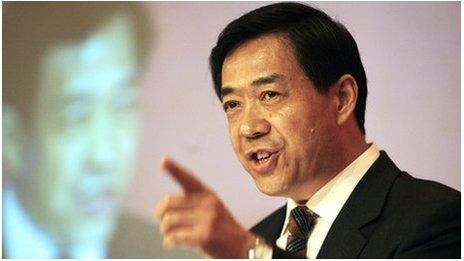

Bo Xilai's life in the fast lane

- Published

His position seemed safe, because his father was one of Mao Zedong's longest-serving and most loyal lieutenants.

So, although eyebrows were sometimes raised in the upper levels of the Chinese political system - "Mr Bo is always so well-dressed," a senior official once said to me, and it did not sound like a compliment - he was able to enjoy an extremely expensive life-style without interference.

His son went to Harrow, the famous British public school, and on to Oxford and Harvard. Mr Bo himself lived in some luxury, especially after he became the party boss of Chongqing, the biggest municipality, not just in China, but in the world.

I first met him back in 1999, when he was mayor of the important port of Dalian. I went to make a documentary on him and his city.

Even then he had a liking for a certain style: on the balcony in front of his enormous office, overlooking the centre of Dalian, he had installed a console which enabled him to choose at the press of a button which colour the water in the fountains throughout the city should be.

Another set of buttons allowed him to change the music which was played through the city's loudspeakers. In those days he had a fancy for Scottish music, so he could select The Bluebells of Scotland, Scots Wha Hae, and The Banks of Loch Lomond, depending on his mood.

The next time I met him, he was China's minister of trade. He was kind enough to say that his promotion was due to our documentary, which had attracted the attention of the party bosses in Beijing. They had decided he was good at dealing with the Western media.

Digging dirt?

It was probably just politeness. His father's closeness to Chairman Mao must have been far more important.

Bo Xilai's time in Beijing was successful, but already there were hints that his lifestyle and ambition were making the party leadership uncomfortable.

He was sent off to be the political boss of Chongqing, and there was speculation, particularly in Hong Kong, that he had been marooned in the provinces to keep him away from the centre of power.

There were also hints that the party leaders might be happy to dig some dirt on him. Rumours about him went the rounds in Beijing.

Bo Xilai headed China's largest municipality, centred on booming Chongqing

In my own case, a Chinese newspaper journalist rang and asked if she could come and interview me about my plans to report on China in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics in 2008. At the time, I thought this was strange, since my visa had not yet come through.

When she turned up, she seemed mostly interested in asking me questions on things I had written or broadcast about Bo Xilai.

At the end of our interview she gave me a card with the name of her newspaper on it. Later, when I checked it out on the web, I could not find any reference to it, and although the telephone number rang, no-one answered.

Mr Bo entered a new and murkier world when he went to Chongqing. The city was largely in the hands of various mafia groups, and he was given the task of smashing them.

This he did with some success, though the methods he and his associates used were sometimes questionable.

Sinister experience

Trading on my previous contacts with Mr Bo, I visited Chongqing a couple of years ago in order to interview him. His officials were always evasive, and it was never possible even to meet him off the record.

Everywhere we went in the city, an unmarked police car followed us. It was quite a sinister experience.

In the end, another official gave us an interview. He was very charming, but there was a long silence when I asked him why we had been followed. It was for our own safety, he said at last.

A lot of curious things seemed to be going on in Chongqing, and some of them were unquestionably linked to Bo Xilai.

His former chief of police, who briefly sought sanctuary with a nearby American consulate and was then arrested by the Chinese police, must have known a great deal about them.

Now, though, the elegant and ambitious Mr Bo has been overthrown. His efforts to remind people of the days of the Cultural Revolution, by sending volunteers into the countryside and giving rousing speeches about China's communist past, are over.

Just as he played The Bluebells of Scotland in Dalian, Bo Xilai took to playing the rousing songs which the Red Guards used to sing during the Cultural Revolution. Maybe that was the final straw for the leadership in Beijing. Bo Xilai has always lived his life in the fast lane.

- Published15 March 2012

- Published15 March 2012

- Published15 March 2012

- Published15 March 2012

- Published10 February 2012