Damaging coup rumours ricochet across China

- Published

- comments

Photos posted on the internet, which were not verified, added to the rumours

Have you heard? There's been a coup in China! Tanks have been spotted on the streets of Beijing and other cities! Shots were fired near the Communist Party's leadership compound!

OK, before you get too agitated, there is no coup. To be more exact, as far as we know there has been no attempted coup.

To be completely correct we should say we do not know what's going on. The fact is there is no evidence of a coup. But it is a subject that has obsessed many in China this week.

Welcome to the weird and wonderful world of reporting on China in the past few days. Coup rumours ricocheted back and forth, most over the internet, but some were picked up by western newspapers, external. China's microblogs were awash with speculation. Hard facts were non-existent.

Purges and power-struggles

Photographs of tanks and armoured cars on city streets were flying around Twitter and elsewhere. On closer inspection though, some of the pictures seemed to be old ones from rehearsals for military parades, others did not even seem to be of Beijing, as they claimed, but different Chinese cities.

China does not look so stable when power struggles are fought in the dark

Many people seemed to believe something was happening, though. The thing that is fascinating is how much traction the talk gained, how far it spread, and what it suggests about China today.

What is most important is that these are not normal times in China. The political atmosphere is tense, full of talk about infighting, purges and power-struggles at the top as China's Communist Party prepares for its once-in-a-decade leadership shuffle later this year.

The Communist Party likes to portray itself as unified, in control - a competent, managerial outfit guiding China towards renewed greatness. It had wanted to show it can handle a leadership change within its ranks smoothly, but now that looks to be far from the case.

The reality of the past few weeks has been that China has been gripped by some of the most extraordinary political events in years, and they indicate significant political tensions beneath the surface.

It began in early February with the flight of Wang Lijun, deputy mayor and police chief of Chongqing to the US consulate in Chengdu where he sought asylum.

'Historical tragedies'

He was refused and was taken away by Chinese state security. That was extraordinary in itself, but the talk was that he had evidence of high-level corruption.

The fallout hit his boss, Bo Xilai, the populist Communist Party chief of Chongqing, member of the ruling Politburo and aspirant for one of the very top jobs in the leadership reshuffle later this year.

A brief official statement announced last week that Mr Bo has been removed from his post in Chongqing. He has now vanished from the scene.

His dismissal came after China's Premier Wen Jiabao publicly reprimanded Mr Bo, warning "such historical tragedies as the Cultural Revolution may happen again".

For one Chinese leader to criticise another so openly was highly unusual, but what really suggested significant tensions was that the premier chose to couple that with the references to the Cultural Revolution, a time of enormous suffering and turmoil in China.

It seemed to be a warning about the dangers posed by Mr Bo and his populist approach.

So the internet in China has been full of talk of power struggles. Chinese microblog users have posted what seem to be leaks of reports about corruption investigations into Mr Bo's family.

'Princelings'

News of Wang Lijun's flight also leaked out through pictures, posted online, of Chinese police surrounding the US consulate. But there is much more going on here than just information leaking onto the web.

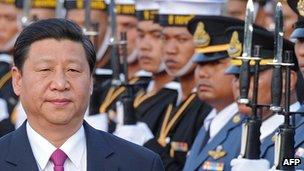

Xi Jinping of the Shanghai faction is tipped to be next leader of the party

The rumours focus on two camps battling for positions. On the one side are President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao and supporters who have risen mainly from the Communist Youth League.

On the other side are the Shanghai faction and the "princelings" including Xi Jinping, the man expected to be the next leader of the party, whose father was a hero of the Communist revolution.

The patron of the Shanghai faction is former President Jiang Zemin. The two factions are generally thought to rotate power between them, but that may be under strain.

Bo Xilai, is also a princeling, backed by "leftists" who liked his high-profile campaigns to help the poor and disadvantaged in Chongqing. Now rumours are rife that one of his main "leftist" patrons in the Politburo, the powerful head of internal security, Zhou Yongkang, is also under pressure and could be ousted.

Intellectual and opinionated

That is where the coup talk originated. Supposedly it may have been an attempt by Zhou Yongkang, who controls China's huge internal security apparatus, to remove Mr Hu and Mr Wen from office.

Chinese microblog users are claiming Mr Zhou has been "defeated by Hu and Wen" and "Zhou Yongkang is under house arrest".

The problem for China's Communist Party is that it has no effective way of refuting such talk. There are no official spokesmen who will go on the record, no sources briefing the media on the background. Did it happen? Nobody knows. So the rumours swirl.

It is hardly surprising that there are splits and power struggles. They happen in every organisation, not just political parties. Those who reach the very top of the Communist Party of China can control vast resources, patronage, power and access to wealth. The idea that the party can be different and avoid such cliques and factional fights seems unrealistic.

But the Communist Party still attempts to control and divide up power in the same, secretive way it has for years. Meanwhile Chinese society has been changing fast around it. The party's very success managing China's economic growth means the country today is no longer the poor, agrarian society of Chairman Mao's day.

China has been transformed. Hundreds of millions of its people are now urbanised, educated, literate, informed, intellectual and opinionated. Many are adept at using the internet to find and exchange information. They know there are power struggles and they are fascinated by what might be happening behind closed doors.

Everyone is waiting to see what the outcome of Bo Xilai's fall and the power struggles will be. But in the absence of any information in China's highly censored and controlled official media, people seize on rumours and speculation on the internet.

The official media, often waiting for political guidance, can be slow and unresponsive. Many in China are now so cynical about the level of censorship that they will not believe what comes from the party's mouthpieces even if it is true. Instead they will give credence to half-truths or fabrications on the web. That is corrosive for the party's authority.

For China's Communist elite, obsessed by projecting an image of unity and stability, this is a serious problem.

The party wants to manage the coming transfer of power smoothly. But keeping things secret and keeping people's trust is not easy to achieve at the same time.

And China doesn't look quite so stable when power struggles are being fought in the dark and talk of a coup can spread so fast.