Bo Xilai scandal: Litmus test for China?

- Published

Bo Xilai's spectacular fall from grace is nothing but a political purge, his supporters say

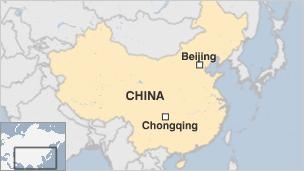

At the Lucky Hotel, high on a hill overlooking Chongqing, south-western China, they were hosting a conference this week for the city's police officers. The subject was disaster prevention.

Crisis management may have been more apt as the death of British businessman Neil Heywood in one of the hotel's secluded villas has enmeshed China's Communist Party in ever-growing allegations of criminality and corruption.

The question that won't go away is how did the 41-year-old businessman die?

The party has promised there'll be no cover-up, that the rule of law will prevail. But as more and more allegations emerge will that happen?

Obsessed by secrecy, the Communist Party has said only that the businessman may have been murdered.

His once powerful friend, Chongqing's former party chief Bo Xilai, has been sacked and is under investigation for breaking party discipline.

Meanwhile rumours swirl, that Bo Xilai's wife ordered the killing of Neil Heywood after they fell out, perhaps over a scheme to move millions earned through corruption to bank accounts abroad.

The tales get more lurid by the day, it's even been suggested that she was there when cyanide might have been slipped into Mr Heywood's drink.

What has been happening in Chongqing during Mr Bo's time in charge of the city has been coming under ever more scrutiny, and what's emerging are tales of corruption, torture, even murder.

Tearful Li Jun - who is now in hiding - told the BBC how he was tortured

'Tiger bench'

Under Mr Bo Chongqing boomed. The city and its surroundings, home to more than 20m people, were his fiefdom. But it seems, his rule was ruthless.

His signature policy was a crackdown on crime, smashing what he called "mafia gangs". Thousands were arrested, dozens executed.

But it now appears many may have not been crime bosses, but those who fell foul of Mr Bo and businessmen targeted for extortion.

So starting to come forward are people who say they are victims too, innocent of the crimes they were convicted of, and who now want justice.

Li Jun, a property developer with assets once worth an estimated 4.5bn yuan (£443m; $714m), and annual earnings of about 1bn yuan, was one of Chongqing's richest men.

He's now in hiding, outside China, and spoke to us from his secret location.

Tears streaming down his face, he tells of how he was picked up by Bo Xilai's police and held for three months.

He was, he says, accused of crimes he didn't commit: organising a mafia, bribery and illegally supporting religious organisations.

He claims he was tied to a metal chair called the "tiger bench", and tortured by Mr Bo's henchmen to make him confess.

"For 40 hours I was banned from going to the toilet or eating. They stabbed me with a pen if I disagreed with them. They slapped me, kicked me, hit me with an ashtray," he says weeping as he remembers his ordeal.

Neil Heywood was allegedly poisoned

"In the second half of 2008 one after another my entrepreneur friends around me, private business owners, were arrested. It sent shockwaves, many businessmen felt scared, more than 1,000 were targeted," he says, adding the campaign was overseen by the police chief Wang Lijun.

It was when Mr Wang fell out with Bo Xilai and fled, seeking refuge in the US consulate in nearby Chengdu, where he revealed details of the investigation into Neil Heywood's death, that the current scandal broke into the open.

Mr Li says he was finally freed after being told to pay a "fine" of 40m yuan. The policemen - who he says tortured him - even took a photo with him as he was released.

Believing he was still at risk Li Jun then decided to flee China, leaving his wife and two daughters - who seven and 14 - behind.

Immediately, he says 30 people, most members of his family, were arrested and tortured, his wife subjected to the "tiger bench" too.

"My brother was taken in and tortured for six days and six nights," Li Jun says sobbing, "whatever the police wrote down he admitted to, thinking by doing so they would spare me. He was sentenced to 18 years in prison. But he's innocent.

"I gave my nephew shares in the company when I tried to escape, he got 13 years. Over 90 bank accounts from my company were frozen, 300m yuan in cash confiscated, my cousin's son-in-law was labelled a mafioso and got four years, my wife got one year in prison."

'Chongqing model'

Chongqing was the fastest growing metropolis in the whole of China under Bo Xilai

As he talks, he holds a photo of his wife and daughters, distraught at the pain he has brought to their lives.

His wife, still in China, ended up, he says with no money, trying to beg funds from his former employees.

"These guys, Bo Xilai and Wang Lijun deserve to be killed. My case is not an individual one. There are tens of thousands of people like me in Chongqing. Bo and Wang wanted to achieve their political goals so they killed people to silence them," he adds.

Before Neil Heywood's death, Bo Xilai's apparent disregard for the law didn't seem to bother the Communist Party. It did nothing to rein in his excesses.

There were complaints, from lawyers, that Mr Bo's crackdown on crime went far beyond what was legal. Lawyers themselves then became targets of the campaign, put on trial after they helped defend some of those accused.

The Communist Party is now keen to say it is enforcing the rule of law by investigating Mr Bo.

But for the past couple of years, in Beijing and across China, the party has overseen a campaign to bring the legal profession to heel. Instead of enforcing the rule of law, it has been securing the party's control over the law.

Lawyers have come under increasing pressure and scrutiny from the party, those who were too independent have had their licences revoked, others have been hounded and harassed, detained and pressured by the police after taking on cases brought by individuals seeking redress for alleged abuses by the party and state.

In that sort of climate it is not surprising that Bo Xilai's campaign against crime in Chongqing was allowed to continue unchecked for so long.

In fact, Mr Bo himself and what came to be called his "Chongqing model" was hailed as a possible blueprint for the rest of China to follow.

Charismatic and with a penchant for self-promotion, Mr Bo was feted as a rising star in the party.

Already a Politburo member and so one of the two dozen most powerful figures in the party, it was widely expected he'd be promoted to the very highest level, the Politburo's Standing Committee, when the leadership is reshuffled later this year. The committee contains the nine figures who really rule China.

He spent billions on popular projects in Chongqing, like vast developments of cheap housing for the poor. The huge state-directed investments helped make Chongqing the fastest growing metropolis in China. Last year it's GDP expanded by an eyewatering 16%, compared with a national average of just over 9%.

Bo Xilai's policies were targeted at the mass of people who have watched others become wealthy during China's two decades of growth, but who have not benefited so much themselves.

Threat and opportunity

His campaigns against corruption, and crime, his revival of patriotism and nostalgia for the "red" values of a more egalitarian past, his vast spending on public projects all won him popular support in Chongqing.

"Bo did great things for the people," one woman told me in Chongqing, "he made sure we don't have to rely on others any more, he's lifted this city up. I hope when this is all over he can come back and run or city again."

As she talked, others in the street market gathered around and nodded their approval. Bo Xilai was, and remains, popular in Chongqing.

It now seems it was his populism and his self-promotion that were increasingly disliked by others at the very top of the Communist Party.

The grey men of the Politburo saw a figure with his own, popular power-base independent of the party as a threat. The death of Mr Heywood provided the opportunity for them to take Mr Bo down.

The party has been at pains to say that the case shows nobody is above the law and it is enforced vigorously. The litmus test will be if it now reopens not just Neil Heywood's case, but those of the businessman Li Jun, and hundreds more.

Will the party examine not just the case of one British man who died, but those of all the Chinese citizens in Chongqing who may have been wronged, some jailed, some tortured, some impoverished, several dozen even executed?

The problem is that opening even one case could implicate dozens of police officers, prosecutors, investigators and party officials in any wrongdoing. That would open China's system up to unprecedented scrutiny.

If the party does pursue justice for all then the Heywood case may be a turning point, a chance to establish the firm principle of the rule of law.

If it doesn't, and many are left to languish in Chongqing's jails and many more never get their names cleared, it will come to look like the Heywood case has been a tool to carry out a political purge, little more.

Mr Li is not confident that China is ready to open up the past. He says he'd like to return, to be with his family, to run his business again, but he says "until China truly has the rule of law and democracy, I'm too scared to".

He believes that for now China still has the rule of the Communist Party, not the rule of law.

So like many in Chongqing, who say they are victims too, he's waiting for the day he can see justice.