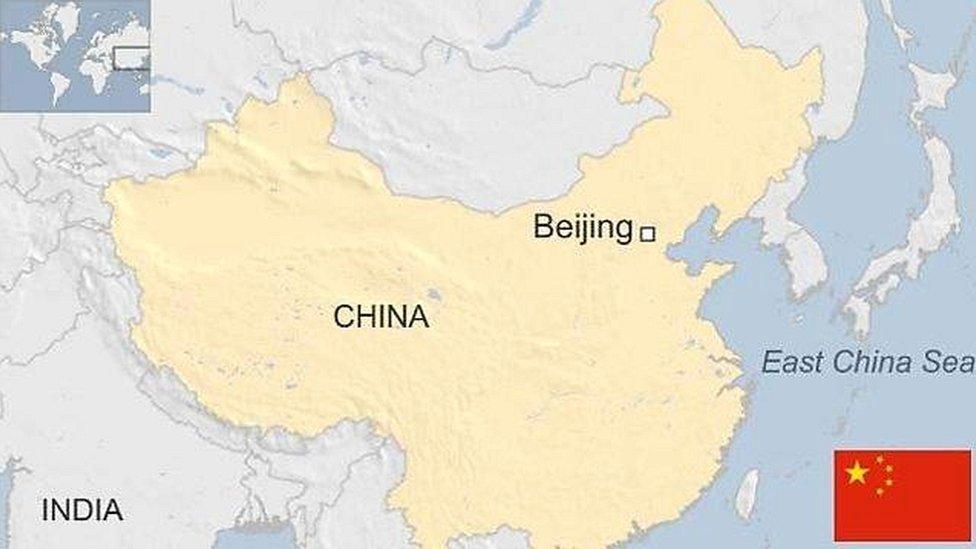

China: Growing old before it can grow rich?

- Published

Mukul Devichand investigates whether China's rapidly ageing population will threaten its future economic prosperity.

China's economic miracle has been accompanied by astonishingly rapid population ageing. Could growing old too fast end China's irresistible march out of poverty?

Where Shanghai leads, China follows. The city is ultra-modern - but also one of the fastest-ageing places on Earth.

One in four of Shanghai's permanent residents is retired

You can see it in the city's vast branch of the furniture store, Ikea. A greying crowd show little interest in flat-pack furniture.

Mr Ni is 72 years old, single and smartly turned out in a tweed cap. "This is a great place to talk to people," he says.

The in-store restaurant offers cheap food to tempt couples setting up home. But this part of the store is buzzing with the elderly, here to flirt and find love.

Mr Ni is a widower whose children have all left home.

"I find it easier to talk to women whose husbands have died," he says. "I know how hard it is."

Ageing metropolis

Under protest, Ikea's managers have set up a special area for elderly singles. All over town, Shanghai is visibly growing old.

"Before he fell, he used to love going dancing," says 77-year-old Mrs Zhang.

She looks across at her husband who is rocking back and forth. Since an accident two years ago, he has been suffering from dementia.

The couple live together in a tiny one-room apartment. "I have to take care of him all by myself," says Zhang.

The glitz of Shanghai's Bund, an avenue of skyscrapers, is close-by. But in the teeming lanes behind the skyscrapers, there are hundreds of fading blocks crammed with the elderly and poor.

The average age goes up as countries develop, because people live longer and have fewer children. But in China, the one-child policy has triggered a rapid decline in the birth rate.

"The speed of ageing in China is unique," says Professor Peng Xizhe, a leading demographer at Fudan University.

China has taken just 20 years to reach an age profile that took Britain or France 60 or 70 years, he says.

New figures show that one in four permanent Shanghai residents is now retired.

The rest of China is catching up - by the year 2050, a third of Chinese people, 450 million, will be aged over 60.

Basic welfare

Mrs Zhang is proud and private, telling her husband to stop talking when he complains. The couple survive on his factory-worker's pension of about £40 a week.

With her only child living away from home Mrs Zhang is responsible for most of her husband's care

She worked in a back-street factory, so has no retirement money.

Local government volunteers visit the couple, but beyond that, care is minimal. Doctors do not make house visits.

Across China, fewer than 2% of the elderly will find a place in a state nursing home, because beds are full.

"I don't have enough money for a [private] nursing home, or to pay someone to come and help," says Zhang, the stress showing in her face.

China's basic welfare system is now struggling with the number of elderly people needing care.

Ten million qualified carers are needed, according to a government committee. So far there are only 100,000 in all of China.

Until recently, this did not matter so much. Traditionally, the elderly lived with their children under Confucian values of "many generations under one roof".

But because of strict birth control, many retirees now have only one child - so that is not an option.

Mr and Mrs Zhang's only daughter lives with her in-laws, returning for a few nights each week to help out.

"Chinese society has not been prepared [with] its pension system and social-security systems," says Professor Peng Xizhe. "People are worried."

Labour shortages

China's leaders worry about ageing, too - but for a very different reason. They fear China's very economic model could be breaking down.

China's export-led system relies on a seemingly endless supply of young, cheap workers. Research suggests that a quarter of China's economic success depends on its cheap labour supply.

Shanghai in particular has relied on rural migrants to mask the problem of its ageing local population.

But in the smog of Yiwu, to the south of Shanghai, it is clear that the supply of young people is disappearing.

There are plenty of empty desks at the jewellery factory

"It's really tough to find new workers, and the cost of labour is increasing," says Jerry Mo, a former foreman who borrowed heavily to open his own small factory two years ago.

His 40 workers snip, mould and bake plastic into costume jewellery items that end up on shelves in Britain. There are lots of empty work stations.

"You can see the way an ageing society is affecting the labour force," he says.

There is an acute labour shortage here.

In addition, migrants - who have their own elderly parents to support - are increasingly quitting to find work in their home towns.

Jerry Mo says his workers demand higher wages but he cannot afford them. "We are becoming unprofitable," he says.

The lack of young workers has hit China's economy just when it needs to pay for the elderly.

There is a Chinese saying about why the country is so worried. China, they say, will become "too old to get rich."

Despite its economic success, China is still a developing country.

"We are really worried about this," says Professor Peng. "In China we have become older but we're still in a very poor situation."

You can find out more about China's ageing population on BBC Radio 4's Crossing Continents on Thursday, 17 May, 2012 at 11:00 BST, repeated Monday 21 May 20:30 BST. Watch a TV report on this page or at the Newsnight website.

- Published25 August 2023