Hong Kong debates 'national education' classes

- Published

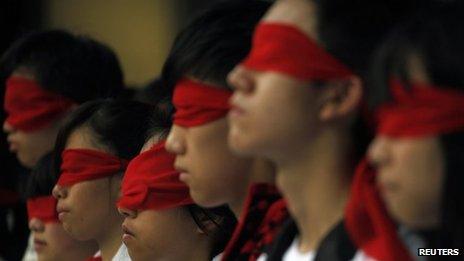

Hong Kong activists are planning more protests on the issue

On a recent rainy Saturday, several dozen parents, students and educators met at the Holy Cross Church in eastern Hong Kong to discuss what they considered to be the defining political and social issue of the decade.

They gathered to debate how to stop the imminent introduction of compulsory classes that critics say is an attempt to brainwash the city's children by the Chinese government in Beijing.

The curriculum, which consists of general civics education as well as more controversial lessons on appreciating mainland China, is due to be introduced in primary schools in September and secondary schools in 2013.

In a town-hall style meeting, the group of about 70 laymen and professional educators expressed anger at the Hong Kong government.

Why, they asked, had the administration refused to do away with the classes when there was such widespread opposition?

Cheung Yui Fai, one of the speakers who is also a director at the Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, said the government's persistence was worrying.

"This is strange, very strange," said the liberal studies teacher. "I think it is odd for the government to stand so firmly when there is clearly so much opposition."

"It makes people think it is carrying out a political mission on behalf of the central government in Beijing."

The row is the latest example of the cultural, social and political gap that exists between Hong Kong and its mainland masters.

It also highlights the deep suspicion with which many Hong Kong people continue to regard the Chinese government.

'Poll plan'

The campaign over the classes is being waged between the city's pro-democracy residents and the Beijing government's proxies, according to activists, academics and lawmakers.

They believe the outcome will help shape the future of democracy in Hong Kong.

"We are sitting on a volcano," said Dixon Sing, an associate professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

"Beijing is trying to speed up the process of integrating Hong Kong in the cultural sense, ahead of elections when everyone gets to vote."

Unlike the rest of China, Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of freedom, including a free press, the right to assemble and transparent, accountable institutions.

CY Leung's government says that the new curriculum is not a brainwashing exercise.

But Hong Kong's restive population is clamouring for the right to universal suffrage, which was guaranteed when the city returned to Chinese rule 15 years ago.

Beijing has indicated that Hong Kong may get that right as early as 2017, when the next chief executive is due for election.

Hong Kong Democrats believe the Chinese government is trying to influence the impressionable younger generation in order to ensure their future loyalty at the polls.

That is why tens of thousands of parents and their children took to the streets in July to protest against the introduction of national education.

Hong Kong's government has shown no hint of retreat, though it has promised to examine the public's concerns.

The Education Bureau says all schools that follow a Hong Kong curriculum must start the classes over a three-year period. Private schools, including international schools, are exempt.

Andrew Shum, a 26-year-old activist who helped organise the July protest, says this campaign is the biggest such movement in the city since 2003, when the government tried and failed to implement a controversial anti-subversion law.

"You know, Hong Kong used to be an immigration city. You arrive on your way to somewhere else, somewhere better. But the younger generation, we don't think that way. This is our home. We want to make it better," he said.

"Even though this isn't a democratic city, we know what freedom is. We know what is human rights. We know that China is our country. But it is not democratising. That is why we want to protect Hong Kong."

'Brainwashed'

These kinds of comments expressed by people around Mr Shum's age are sure to be alarming to the Chinese government.

A child wearing a sticker that reads, "No brainwashing" during a protest in Hong Kong in July

From the Chinese government's perspective, instituting a form of national education to teach Hong Kong students to appreciate and love the motherland is not controversial.

After all, students in China are fed a much stricter, more politicised diet from their early years. Many other countries also offer courses on national history.

As their thinking goes, 15 years after Hong Kong's return to China, residents in this capitalist city should have a stronger Chinese identity.

And according to an editorial in the Global Times newspaper, a tabloid that operates under the official Communist Party mouthpiece the People's Daily, Hong Kong people need the classes because they have already been brainwashed.

"The objection to it by some Hong Kongers seems quite exceptional from a global point of view," it writes.

"In fact, those who oppose it are likely to be more 'brainwashed' by Western ideology, as Hong Kong used to be a British colony."

The opinion piece, which preceded a more strident editorial in People's Daily, argues that the new course will "expand the vision" of Hong Kong people, enabling them to adapt more smoothly to the national environment after the handover.

Goodwill tours?

It is far too soon to tell how the long-running conflict between the Democrats and the pro-China forces will be resolved.

Hong Kong enjoys a high degree of freedom, including the right to assemble

For now, both sides are trying to win the hearts and minds of Hong Kong residents.

The government of Chief Executive CY Leung has been trying to assure the public the new curriculum is simply an extension of civic education and not a brainwashing exercise.

But the visit of China's newest astronauts in early August and a victory tour by the country's gold-medal winning Olympians - within weeks of each other - made many residents suspicious.

They believe both were propaganda exercises and not simply goodwill tours by China's brightest stars.

On the other side, the Democrats - led by the coalition of teachers, parents and students - want to send an unmistakable message to the Hong Kong and Beijing governments.

Mr Cheung, the union leader, is planning a city-wide strike by teachers on 3 September, the start of the school term. His union has about 90,000 members, the largest group of educators in Hong Kong.

But he admits that persuading members to commit to the strike is difficult because they may face pressure from school administrators.

- Published7 January

- Published1 July 2012

- Published23 March 2012