Ageing China: Changes and challenges

- Published

It is more than a decade since China officially became an ageing nation, and since then, the country's ageing process has only picked up speed.

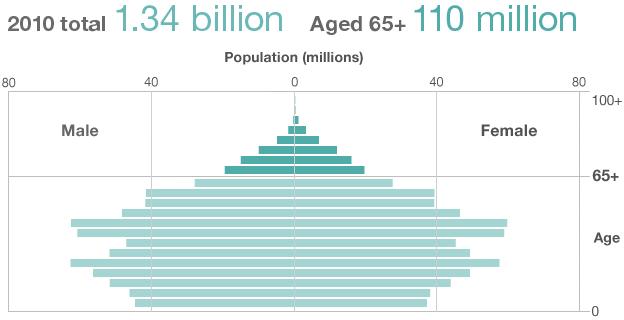

In 2000, its number of people aged 60 or over surpassed 10% of the total population, and almost 7% of the population were aged 65 and over.

According to government figures, at the end of 2011, when the total Chinese population reached 1.34 billion, 13.7% of the population were 60 or over - that's 185 million people.

Those aged 65 or over accounted for 123 million people, or just over 9%.

Faster, faster

The ageing process in China has two distinguishing features. First, it has happened at a much faster rate than in other countries.

According to UN figures, the ratio of those aged 60 and over across the world rose by 3 percentage points in the 60 years from 1950 to 2010, while in China it increased by 3.8 percentage points in just the 10 years from 2000 to 2010.

Secondly, China is one of a few countries in the world in which the population has aged before becoming rich or even moderately rich.

The UN considers a country to be ageing when 7% of its population is aged 65 or over - the threshold used to be 10% of a population being 60 years old or over.

While more than 60% of the world's ageing nations reached that threshold when their GDP per capita exceeded $10,000 (£6,215) - and 30% reached the threshold when their income reached $5,000 - China officially became an ageing country when its GDP per capita was less than $1,000.

This inevitably means there are more financial constraints when it comes to any potential solutions.

Being old costs more

China's unprecedented demographic transformation has been mainly caused by a significant increase in the country's life expectancy. People are living longer life thanks to significant improvements in living standards, including improved nutrition, access to education and medical care.

Another factor is China's one-child policy, which was imposed by the state in 1980. According to a government, this caused a sudden decrease in the country's birth rate and prevented 400 million extra births over the past three decades.

There is debate among scholars over the exact figure. Some say the drop in birth rates was typical of that which occurs in societies as they modernise, others say it at least slowed down the population growth and therefore speeded up the ageing process in China.

This rapid ageing has led some economic and social consequences.

Many of those are the same experienced by other ageing nations, such as a huge fiscal deficit due to soaring pension expenses and increased medical costs. But being a less developed country experiencing a faster ageing process than most has made things difficult for China.

There are also some consequences particular to China. Probably the most important consequence will be a rapid decline of labour force.

There are currently 980 million people in the active labour force in China. According to Professor Zhen Binwen of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, this number will reach its peak in 2015, but then start to decrease dramatically.

Younger generations may struggle to keep their heads above water

End of cheap labour?

Professor Cai Fang, a Chinese labour economist, estimates that the rapid decrease of the labour force will lower China's annual growth rate by 1.5 percentage points from now to 2015, and it will decrease a further percentage point during the period from 2016-2020.

China's demographic dividend will end - the country's fast economic growth in the past three decades has been mainly led by exports, which are dependent on an abundant and cheap labour supply.

A fast decline of the labour force will cause shortages and a rapid increase in wages. Such changes will weaken the competitiveness of China's export industries in the international market, affecting economic growth.

China will need to undertake dramatic economic restructuring to deal with this problem.

The rapid ageing process will also bring with it political difficulties. The legitimacy of Chinese communist party as a ruling group of the country since the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989 has been based on its maintaining rapid economic growth.

An economic slowdown could prompt challenges to party's legitimacy.

Existing disadvantaged social groups, such as migrant workers and pensioners, especially those in rural areas, will be most severely affected, and the social unrest sometimes experience in China now could become increasingly common.