Viewpoint: Fear and loneliness in China

- Published

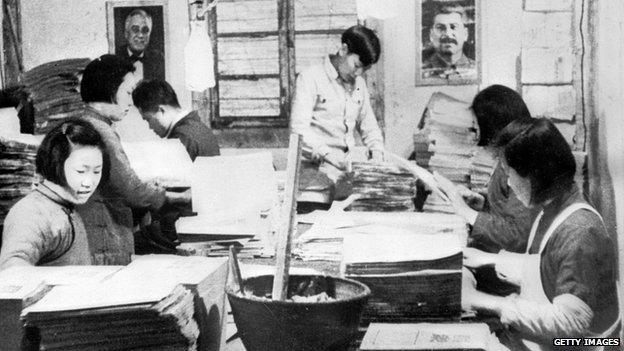

In the Mao era, the cramped factories set up did also manage to foster a sense of community

What kind of society will China's new leaders inherit? China has developed at unimaginable pace, lifting millions out of poverty. But as part of a series of viewpoints on challenges for China's new leadership, Gerard Lemos, who conducted research in the mega-city of Chongqing, says it is easy to overlook its lonely underbelly.

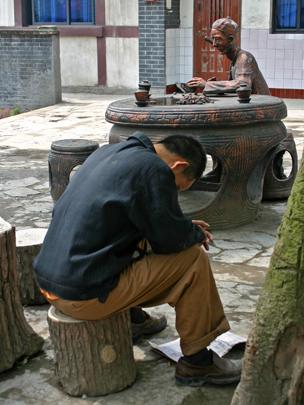

An old man was hanging upside down in the public square. His feet in traditional cloth shoes were over the parallel bars from which he had suspended himself, for what were presumably his morning exercises. He was fully clothed and in a padded overcoat to combat the spring chill.

I saw this when visiting a factory community in Beijing in 2008. On the face of it, this was a peculiar act to perform in a public space, but people walked past taking no notice. In such traditional Chinese communities, this public square served as a communal living room; most of the people around are friends and neighbours. Not being surprised by the unusual behaviour of your neighbours is an aspect of intimate community life.

But this kind of sight will become rarer as a changing China sees the fragmentation of these communities.

When I was a visiting professor at a Chinese university I was asked by the government's civil affairs bureau to find out people's fears and dreams to help the authorities better understand the risks of social unrest.

In the Mao era factory units, between the smoky brick factories and chimneys and cramped, dark flats was a bare concrete public space like the one where this old man was exercising.

Because people lived in such uncomfortable and overcrowded conditions, these public spaces were claimed by residents taking exercise, spontaneous groups performing tai chi or playing Chinese chess. Old men would take their caged songbirds out for some air and a change of scene.

But this way of life is disappearing, in the cities and in the countryside. For many in China isolation is a new experience brought on by economic transformation. In the neighbourhoods where I worked in Chongqing and Beijing, loneliness was spreading like pollution.

The new leadership scheduled to be announced in November will not just have to address failing economic growth and foreign policy dilemmas such as regional territorial disputes, but also the absence of a social safety net, the consequences of the one-child policy and the unhappiness of migrants to cities and factories.

High-rise isolation

For many in China rapid economic growth has led to loneliness

For many in China isolation is a new experience brought on by economic transformation.

From the 1950s to 1970s people were allocated to factory units for life by the Party authorities. Megaphones blared propaganda continuously. Workers had to sing Maoist songs, wear uniforms and participate in daily group exercises. Party officials were everywhere and permission was needed for everything, including getting married or moving house.

But there was an upside. The residents were promised a job for life, a free school and clinic. The intention was they stayed in one place all their lives, though the Cultural Revolution threw that into turbulence. Over time living side-by-side turned neighbours into families and families became communities, however hard their lives.

Since the 1990s the factories have been closed and demolished. Farmers' land near cities is being sold for development into high-rise flats.

One ex-farmer in Chongqing whose land had been confiscated told me: "My land being expropriated [changed my life. I wish] to have my own land and to live my life as a peasant farmer."

Another was worried about where he would live now that his land had gone: "[My greatest worry] is having no place to live. [I wish] to have more living places built for the peasant workers." Another said: "[I wish] the urban residents who have just changed from rural residents could all get employed."

In fact, longstanding residents are evicted from their homes and given a small flat and minimal financial compensation in the least desirable accommodation. Either there is no public space or it is far away and soulless. Employment prospects for ex-farmers are poor or non-existent. There is nothing to do except stay indoors, watch TV or gamble on the stock market - now, some believe, approaching a national obsession.

Millions of mostly young people have moved to the east coast to work in factories and live itinerant and restricted lives. The hours are long and the work is repetitive. The workers, many young women, live in dormitories and are corralled with other people from their region under the watchful eye of an overseer from the same part of the country.

They work hard, save assiduously, send money home and if they lose their job, they often don't go back, because they cannot face the shame of returning home unemployed and no longer supporting their families.

Some, in desperation, are driven to prostitution to maintain their remittances home. Sex can be bought for less than £1 ($1.60) under a bridge or flyover in Sichuan. Suicide rates are so high in some of these factories that the owners have put nets around them to break the fall of people jumping out of windows.

Lonely children

Back home the parents of these "factory girls" are left alone to grow old without the care of their children - breaking a long Confucian tradition of caring for elders.

As one man in Chongqing told me: "I'm a lonely old fellow. I have had good service for the elderly [from social workers]. I hope this service will carry on." This old man was facing a fate unknown in China until recently, but all too familiar in the West. "I hope the old people's home can be built quickly," he said.

In many villages there are no young adults, just old people and a few of their grandchildren sent back to the countryside. Old people without family support and few financial resources have to fall back on social workers.

The one child policy has made children lonely too. Without siblings for company or rivalry, all their parents' and grandparents' expectations rest on their young shoulders, bringing untold anxiety and pressure. As one 11-year-old boy told me: "I'm worried in the future I will not be a good student and I will disappoint my parents. I hope I can go to university and make a positive contribution to my homeland."

Play and the pleasures of childhood are hard to fit in around homework. One girl told me: "I have little time to get rest because I need to study hard every day and to learn singing… I wish to be a very good student and to become an artist when I grow up."

The old restricted, hierarchical, multi-generational families built on Mao's authoritarian utopianism and an older tradition of Confucian values have been replaced by isolated and impoverished old people, listless ex-farmers, hard-pressed factory girls and children trying to cope alone with extreme educational pressure and unrealistic family expectations.

Loneliness, ineradicable and irreversible, coupled with anxiety about the unpredictability of the future, could become pervasive across all generations in China.

- Published24 September 2012

- Published20 September 2012

- Published2 October 2012

- Published8 June 2012