Viewpoint: The power of China's strolling eco-warriors

- Published

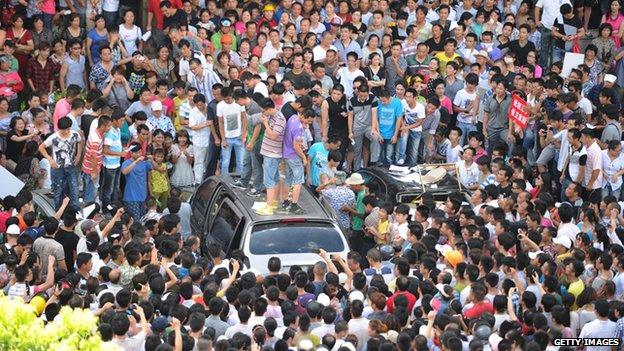

Chinese citizens are increasingly taking to the streets to protest against perceived environmental threats

In China a tiny number of officials make key environmental decisions. But an increasingly savvy public could take to the streets unless the government changes its approach, argues environmental campaigner Ma Jun as part of a series of viewpoints on challenges facing China's new leaders.

In August 2011 about 12,000 people in China went for a "group stroll" in the northern city of Dalian. But this was no ordinary Sunday morning walk - it was a protest by another name, in a country where dissent is controlled.

The strollers carried banners voicing their rage at a chemical plant in the area. In China these strollers eventually forced the government to announce the relocation of the 10bn yuan ($1.6bn; £1bn) plant.

China has witnessed remarkable economic successes over the last three decades, accompanied by industrialisation and urbanisation. But ordinary people are coming to understand that this comes at a cost.

Citizens are beginning to see that development based on ever-greater consumption of resources is unsustainable. When China's new leaders take control, they will be confronted with a population increasingly protective of their environment.

China leads the world in energy consumption, carbon emissions and the release of major air and water pollutants, and the environmental impact is felt both regionally and globally.

Yet local officials have stuck with this model of development because it promotes GDP growth, and such measures are closely tied with their personal political careers.

They believe that the day when concerns over the environment and availability of resources actually constrain growth is far away.

Many others believe they are wrong.

People power

Over the last year, these environmental constraints have been felt in sudden and unexpected ways. August 2011 saw the mass protests against the PX chemical plant in Dalian, and this was followed by public protests against a metal smelter in Shifang and rallies against a waste-water pipeline in Qidong.

Faced with tens of thousands of "walking" protesters, the regional governments compromised in all three cases, cancelling huge investment plans or committing to relocate facilities on which tens of billions of yuan had already been spent.

These cases have far-reaching implications.

First, it shows that the public is more environmentally aware than ever before and reacts strongly, perhaps radically, to health risks. Second, microblogs and other social media have given people the tools to discuss social issues and to organise. Third, the government is reluctant to use force to suppress public actions which are aimed at defending fundamental environmental rights and health.

And so the new leadership in China, which is set to take the stage after China's Communist Party Congress in November, will face a major transformation unseen in China for 30 years.

For the past three decades, China's top-down and opaque methods of managing the environment have allowed for the fast-track sanctioning of large-scale projects in line with already approved plans, and ensured that those projects are not disrupted by local communities. Rapid economic growth has ensued.

But incidents such as those in Dalian have shaken this system. If this trend is not handled properly, not only will it be hard to achieve both development and environmental protection, but social stability may be at risk.

Things must change. But how?

Increasingly it is understood that the biggest obstacle to environmental protection in China is not a scarcity of funds or technology, but a lack of motivation.

We have created laws and regulations but the enforcement remains too weak and environmental lawsuits are still very difficult to file. Regulatory failings mean that the cost of breaking the law is far below that of obeying it - businesses are happier to pay fines than to control pollution.

Behind those failures lies an environmental management system in which every decision is still made by a tiny number of officials, developers and experts who make compromises at the expense of the environment and local communities.

Many of China's waterways have been polluted as the country has grown richer

Knowing the risks

It has been shown that public participation can limit powerful interest groups, while competing interests can help find a reasonable balance between development and environmental protection.

But China's environmental conundrums will not be solved by changes within government alone. New mechanisms are needed to allow the communities which may be affected by a given plan, and citizens concerned about the environment, to join in.

The cases in Shifang and Qidong have made many, including sensible government officials, rethink the top-down environmental management system. China needs to proceed step-by-step in the short term, but in the long run there needs to be a clear framework supported by key rights.

The environmental right to know, or giving the public the right to access information held by the government, is critical. If the public is unaware of environmental risks or decisions being made, or cannot get hold of any environmental data, participation becomes meaningless.

After that comes the right to participate. This is also crucial, as information itself will not clean up pollution.

Finally, the right to seek judicial redress comes into play when the first two rights are infringed upon, and again this requires further judicial reform.

Over the coming decade, we can predict that the public's environmental awareness will continue to increase and that there will be greater willingness and ability to take action.

Environmental change will inevitably occur.

But only a new approach to managing the environment, founded on fairness and transparency, and with open participation at its heart, can provide the motivation to ensure China's sustainability.

- Published3 July 2012