Viewpoint: What Chinese women really need

- Published

For generations, rural women toiled hard but have been forgotten in China's race to the top

Mao Zedong once said that in China "women hold up half the sky". But decades on from the revolution that transformed Chinese society, writer Xinran asks whether women really have inherited all that was promised, as part of a series of features on challenges for China's new leaders.

At critical junctions, China likes to change driver as it continues its journey on the political road it was set upon in the 1950s.

Of course, the drivers are always men. This is a real "man-made" culture, even though Mao himself famously gave half the Chinese sky to women.

Since then that half-sky has been more about how women should stand up and liberate themselves, in line with global women's liberation movements.

The Chinese press will tell you that Chinese women have managed to claim that half-sky quite well - first of all by getting their names back after the 1,000-year old "marriage rules" which endured through centuries of feudalism. Chinese women now have the right to retain their maiden names.

Further, women have been freed from the expectation of an arranged marriage and won the right to pursue education, to compete for the same jobs as Chinese men and, most importantly, to be part of China's super-rich.

But you can still see and hear different stories in China's countryside and in one place in particular that I have visited, just a five-hour drive from the shining metropolis of Shanghai.

I have been back twice a year ever since I left in 1997. The Chinese women I have met and researched over the last 30 years or so are largely migrant workers and peasants.

Many factory girls have told me they are happy because their monthly income of less than $160 (£100) is much more than what villagers would get from working the land all year round.

But migrant mothers often express worries about their children having no school to go to in the city where they work, either because of the high cost (a school term costs over $1,600 - more than what they earn over three years) or the school's policy to only take children who are from that city.

So grandmothers in many of these countryside communities carry on working the land and looking after their grandchildren with aged painful bones.

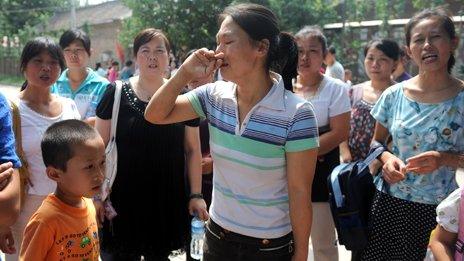

Female migrant workers are grateful for the pay but work many miles from home

Such women are not part of the picture of the new China that is being built up and they tell me they have no idea how to comprehend the city life they hear about from their city-worker children.

These Chinese women are an important part of the 1.3 billion Chinese - their lives are tough and they work very hard.

They are everywhere, shuttling between cities and countryside - but they are invisible to government policy and the respected education system is blind to them.

In a previous era China was too male-dominated to bother to even think about the women. Today's China is simply too busy to remember them.

I finished my new book about the first generation of the country's one-child policy earlier this year. I struggled all the way to the end, mostly because I couldn't find information about these mothers from their children's memories to reconstruct a picture of family life.

This was because their parents were too busy to cook, read to them or even be with them; the children were too lonely to understand that they could have more from family besides inherited money.

Traditional Chinese family values have been corrupted not just by American dollars and European labels but also by those who choose only to follow the path to riches.

But what else have we lost?

I was born and raised in Red China when my parents both devoted their time and family life to the political party and country. They were encouraged to believe that parents should not care about their children more than their work.

My son Panpan was born in 1988 when China opened up to the world. I wanted to be different from my mother, to give my son a better childhood; therefore I was shocked when Panpan asked me to spend 10 minutes with him as his 12th birthday gift! This was a dream I recognised - as a child I wanted the same from my mother.

One of the key concerns for migrant workers is the education of their children

So, why? We grew up in such different times and places and yet have the same hunger for a mother's love and care. I don't think that was all down to the one-child policy.

But by 2025, there will be 20 million more young Chinese men than women, according to the National Bureau of Statistics - one ironic side-effect of the one-child policy will be the high value of these young women.

The women of China are important not just to the children who need them, but also for the country's future.

China has survived two critical and dangerous junctions in the past few decades. The first was allowing millions of peasants to flood into the cities without state control and the second was opening the door to the world without being beaten by other world powers.

Now China has arrived at the third junction. The 18th Congress is likely to appoint Xi Jinping as the country's new driver in the presidential post. As usual, everybody knows this fact before the "Chinese election".

Whatever he is going to do, I wish Mr Xi would be brave and strong enough not only to fight with the Chinese political mafia and free up some of the country's "cultural sky" for an open media, but also to take time to listen to Chinese women - and to bring true power to those extremely hard-working Chinese women living in poverty.

China would not be here today without those mothers and grandmothers; they should not be left in those forgotten corners.

- Published22 September 2015