China's ever-widening wealth gap

- Published

- comments

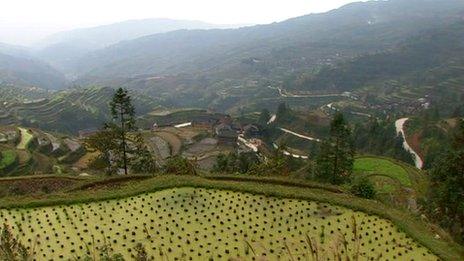

Farmers in Guizhou earn little from their hard work

In China's poorest province paddy fields stretch down the mountainsides. Here and there farmers squat, working in the mud.

Men thread their way through the patchwork of fields, balancing heavy sheaves of rice just harvested from poles slung across their shoulders.

Over generations Guizhou's hillsides have been shaped and sculpted by hand. It's work that continues today. There's no sign of any mechanisation in these remote hills.

Tiny villages with creaky, old wooden houses dot the valleys. It's picturesque but it's also a place of poverty.

Lu Jikuan's bare feet squelch through the mud. High on a hillside the 70-year-old is bent double, cutting grass along the edge of his rice paddy with a scythe.

"I've seen rich people, on TV, living in nice houses, driving fancy cars," he says, a grin exposing his missing teeth. "I dream about having that kind of life. But I know it's just a dream."

Instead he makes do with a government pension of 55 yuan ($8, £5) a month and what little more he can earn from selling the occasional calf or pig.

The economic boom in China's cities and along its coast is happening far from here.

In China's richest places, like Tianjin, Shanghai and Beijing, average incomes at over $10,000 a year are now on a par with some European countries.

Here in Guizhou average incomes are a bit more than $2,000, more akin to Sudan or Nigeria. In the province's remote districts even that level of income is way beyond many.

'Not fair'

The little hamlet of Xiage echoes to the sound of firecrackers. Guests file up the wooden steps that lead to Lu Dayi's house. He has recently got married and all his relatives are here to celebrate the arrival of his first child.

The men make toasts with bowls full of wine, then use their fingers to scoop lumps of sticky rice into their mouths.

Many people in Guizhou live below the poverty line

They are all farmers, thin and wiry, dressed in ill-fitting blue jackets and caps that are grimy and stained from their work in the fields. Cigarette smoke fills the air. Bushels of harvested rice are piled all around.

Gifts arrive, including a refrigerator and a new bed.

Lu Dayi could never afford these himself. He says he has earned nothing from his land this year and cannot grow enough to feed his family.

"I've seen, in the city, people living in big houses, in such nice skyscrapers," he says, "but if you look around here, the houses are just wood and bricks."

"It's not fair. I've been to the cities and seen bosses eating in fancy restaurants every day. They're rich. My life doesn't compare."

"If I had a lot of money I wouldn't mind spending it on an expensive meal too. But I don't. My heart aches when I spend money because I have so little of it."

Lu Dayi is one of over 150 million Chinese in the countryside still living below the poverty line - officially set at around $1.5 a day.

China's economic growth has been deeply uneven. Most have seen their lives improve in the past two decades, and 400 million Chinese have lifted themselves out of poverty.

But those in the right places with the right connections, usually in the cities, have gained incredible riches. So China today is among the most unequal countries in the world.

The serious and growing inequalities are a problem China's next leaders know they must tackle as the gap between the rich and the rest grows wider.

'Elite' lifestyle

Beijing is three hours by plane from Guizhou. It feels like a different country.

China's capital is now a megacity of almost 20 million, its streets hectic and clogged. The world's most expensive brands have huge outlets targeting China's new urban elites.

At a recent polo tournament, sponsored by Cartier, they arrived in their Rolls Royce limousines and Porsche SUVs.

One and a half million Chinese are now dollar millionaires. And the country has an estimated 250 billionaires, up from just 15 in 2006.

This part of China's society has joined the global rich league. They dress in designer outfits that cost more money than Lu Dayi in his village has had in his lifetime.

"People want better things in their life now," says Guo Pei, a fashion designer who came to watch the polo.

"In the West polo is part of the lifestyle of the elite. We too are rich now so we want what's fashionable and sophisticated. It's natural."

So those with money aspire to Western-style leisure and luxury. On the edge of Beijing stands a replica French chateau, complete with turrets and towers, and even its own vineyard and cellars.

China's middle class is picking up new habits, such as appreciating wine

It was built at a cost of $300m. Families can have a go at treading the grapes, then they sample the wines.

The most expensive vintage, grown at the chateau, sells for $1,500 a bottle.

The place also attracts China's new middle classes too. In front of the chateau Jia Zhiyao and Cao Pengfang pose while a professional photographer snaps pictures for their wedding album. She's in her wedding dress. He's in the outfit of a European dandy.

The couple, who both work for a Beijing real estate agency, are paying $1,500 for the album.

The cost is almost their combined monthly income. But they hope the pictures will impress their relatives who live in the provinces and have never left China.

And although their income makes them middle class, in China today they don't feel particularly well off.

Life in the cities is becoming increasingly expensive and, as inequalities rise, even the middle classes are being squeezed.

"Well, our lives are better than the poorest. But we're far worse off than the rich. It's not great, we're stuck in the middle," says Cao Pengfang.

The biggest problem they face is buying a flat to live in. Property prices have risen so fast that Cao Pengfang and Jia Zhiyao cannot afford anywhere in Beijing.

They say they will probably move back to their hometown.

'Urgent task'

Back in Guizhou 70-year-old Lu Jikuan is making rice wine at home.

The poorest feel stuck too, in the countryside.

Money is being poured into Guizhou. New roads carve through the hillsides, mile after mile of tunnels have been bored through the mountains. A new airport terminal is being built in Guiyang, the capital.

Chinese leaders say closing the wealth gap is a priority

The province is pushing itself as a tourist destination and its economy is now among the fastest growing in China.

But the problem for China's leaders is that while the country's economic success has been extraordinary, the divisions are becoming starker.

Premier Wen Jiabao, who's soon to retire, has said narrowing the income gap is an "urgent task".

His decade in power, which is now drawing to a close, was meant to create a more "harmonious" society. Instead inequalities have risen.

So the job of making China a fairer place will now fall to the Communist Party's next generation of leaders, who will rule the country for the next 10 years.

The fear is that China's growing inequities could undermine the legitimacy of their one-party rule, and the more unequal China becomes, the more unstable it may be.