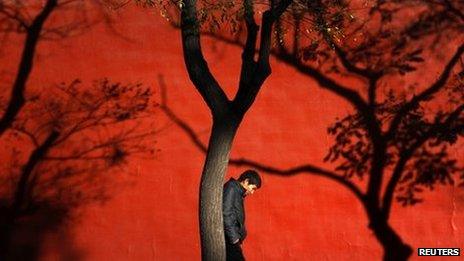

China at a crossroads amid leadership change

- Published

No-one, not even the self-appointed experts, knows what will happen next

Every academic, every commentator, every blogger you speak to here tells you China is at a crossroads.

Ordinary people in shops and offices tell you same thing; though perhaps they get it from the commentators and bloggers, of course.

What does it mean, in practical terms? Essentially, it means that no-one, not even the self-appointed experts, knows what is going to happen - except that things are unlikely to remain as they have been up to now.

All we do know is that a new leadership is about to take over.

Like the two previous leaderships during the past 20 years, they will no doubt start off much like their predecessors, but will soon establish a distinctive character of their own.

Game for karaoke

After the last leadership change-over in 2002, for instance, the pattern at first seemed unchanged. China was regarded in the West as basically friendly.

The two top figures from the outgoing leadership, President Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji seemed relaxed and easygoing.

When they went abroad they were jokey, inclined to dive into crowds and all too willing to join in karaoke if there was a chance.

People are now chatting online about politics and society, although there is still strong censorship

Since then, though, we have had 10 years of the more stiff and serious Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao. China's economy and power have grown hugely, and many more people in the West have begun to see it as a threat.

An angry form of Chinese nationalism surfaced on a big scale in 1999, when Nato bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade. It is a force which the Hu Jintao leadership has consciously encouraged ever since.

And yet there is a different and no less important force which the Hu-Wen years have fostered less deliberately. Those years have been a period of extraordinary improvement in personal freedom in China.

The result has been that many younger people in the big cities feel they scarcely occupy the same country as the old, uptight Communist leadership. To them, it seems increasingly irrelevant to their lives and futures.

'Another world'

We saw exactly the same process in the old Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, as Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of glasnost and perestroika took effect.

China today is certainly not the same as Russia, Hungary, Poland or Czechoslovakia 23 years ago, but there are some startling similarities.

In District 798 in Beijing, for instance, which was once a complex of armaments factories and has been turned into a sprawling colony for artists and art galleries, the only reminders of Communism are the irreverent paintings and sculptures making fun of Mao Zedong and his acolytes.

Precisely similar things started to appear for sale in Moscow's Ismailova market at the end of the 1980s, and its equivalents in Prague, Warsaw and Budapest - only they made fun of Stalin.

Much more important, the conversations in the cafes of District 798 now are immensely reminiscent of the old days of the break-up of the Soviet empire.

"I don't feel the government has anything to do with me at all," a smartly dressed young woman told me, as she drank a cafe latte. "It's another world as far as I'm concerned."

And indeed the stiff, awkward rows of Communist Party delegates sitting bolt upright in their identical black suits, white shirts and red ties, only worn on big occasions like this, applauding their leader at specified moments in his speech, scarcely seem to belong on the same planet as the relaxed, Westernised artists strolling round District 798.

Each group probably thinks it represents the real China, and of course the reality is that there are a billion or more people outside Beijing who have nothing much to do with either.

Historic change

China's economy and power have grown hugely

But it was this kind of division, between an ageing Party and the young intellectuals of Moscow and Leningrad (soon to be St Petersburg again) which caused the collapse of Marxism-Leninism, first in Eastern Europe and then in Russia itself.

Which brings us back to the idea of the crossroads.

The new president, Xi Jinping, knows the West in a way none of his predecessors did. His daughter is studying in the United States at the moment, and he has spent time there too.

True, he will not be able to act on his own: he will have to persuade the rest of the Party leadership to go along with him. Still, he may represent a shift back to the apparently friendlier days of Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji.

But suppose the economy starts to go really bad - will the new leadership be able to resist the temptation to put the blame on the outside world?

All the instruments to work up a fierce Chinese nationalism are in place already. We saw them brought into play recently against Japan. This, after all, would be an easy way of bringing all those intellectuals and artists who feel alienated from the system back into the fold.

Or maybe China will continue to grow, even if at a lesser rate, and the Communist Party will stay peacefully in control, keeping everybody happy. Who knows?

One way or the other, it does feels as though this Party congress will change the course of history. And the last time I felt this quite so strongly?

It was in Moscow, back in 1988.