Reforming China's gulags

- Published

The camps are a throwback to China's Maoist past

China's new Premier Li Keqiang has signalled his government is prepared to start the process of reforming the widely-despised system of re-education camps.

The camps, a gulag-type network created half a century ago, hold thousands of inmates who are made to undergo "laojiao", also known as "re-education through labour".

But the case of one woman, Tang Hui, sent to a camp last year, galvanised public opposition to the system. Reforming it would be a significant legal step.

Tang Hui took us to visit the camp where she had been held, tucked into a fold of hillside, an hour or so from Changsha in Hunan Province.

Re-education involves chants and performing exercises

The Zhuzhou Baimalong Labour Camp is an imposing sight, built like a prison.

At the front there's a giant, curved facade, lined with classical columns, where the main gate stands. Behind it is a sprawling collection of white buildings, some six or seven storeys high, with workshops, vegetable gardens and a parade ground, all surrounded by a high wall and watchtowers.

The camp is just one component in China's sprawling gulag system, known as "laojiao". These camps are a throwback to the years just after China's Communist revolution, and many outside China don't even know they still exist.

There's a constant flow of police vehicles and buses in and out of the camp. It's big enough to hold hundreds of inmates, all sent here to undergo "re-education through labour". You see them every now and again, in lines, walking from one building to another, performing exercises.

Drifting on the wind you can hear the chants of inmates, undergoing their forced re-education. Just an order from a policeman is enough to have you locked up here for as long as four years.

Tang Hui, a former inmate, guides us closer to the huge camp gate. Her incarceration here last year caused outrage in China.

"It was living nightmare. A real nightmare would have been better. I could have woken up from that," she says, dissolving into tears.

'Act of revenge'

Tang Hui was held at Zhuzhou Baimalong Labour Camp for nine days

Her ordeal began in 2006 when her 10-year-old daughter disappeared from home. Unbeknown to Tang Hui, the girl had been raped and then lured to a local karaoke centre by a man she'd met. There she was gang raped again by four men, beaten and forced to work as a prostitute.

Local police did little to track down the missing girl, saying she'd probably run away from home. Tang Hui didn't give up and, after three months searching her hometown of Yongzhou, discovered where her daughter was being held. Only then did the authorities act, freeing the girl and arresting her captors.

Tang Hui campaigned vigorously for the death penalty for the men who did it. But she says the pimps had powerful connections in the police force, and the bad publicity the case brought may have tarnished the careers of local officials.

So those same police and officials had Tang Hui sent to Zhuzhou Baimalong camp to undergo 18 months of re-education. She says it was an act of revenge to silence her. Her re-education meant being told she must obey whatever the Communist Party says.

"I felt desperate, but I didn't shed a single tear, because I knew they were monitoring me all the time," she says.

"They wanted me to break down. They told me: 'If you promise to drop your case you can leave this place early.' I told them I would never write such a promise."

'Illegal and wrong'

Like all of those sent to labour camps Tang Hui went through no legal process. There was just a written order and she was shut away. Her lawyers used the internet to spread word of her incarceration. It caused uproar and she was released after nine days.

Many in China hate the labour camps and want to see them disbanded

"After my re-education I realised my mistake," she says.

"I'd pursued justice for my daughter because I thought the Communist Party was there for me. I thought the government and police would back me up. But I don't believe that any more. They've treated me like an enemy. They attack us instead of protecting us."

China's re-education through labour system was set up in the 1950s to silence political opponents. Today it's used to lock up undesirables like drug addicts and prostitutes, along with those like Tang Hui who complain too loudly about injustices, or people who are members of religious movements banned by the Communist Party.

Beijing lawyer Pu Zhiqiang says the whole system goes against China's own constitution and the rights its citizens should enjoy.

"Re-education through labour is illegal and wrong," he says. "People have their freedom taken away without any court case. They can't even appeal the decision until after they've served their time. It's a sign that China remains a police state. Not a country with the rule of law."

China's new leaders, aware the system is deeply unpopular, have indicated they are considering reforming it.

New Premier Li Keqiang, in his first news conference on Sunday, said authorities were "working intensively" on the plan to reform the system, and the plan "might be unveiled before the end of the year".

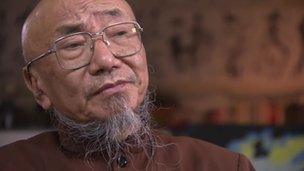

Li Zhengtian says he was beaten during his period of re-education

Some had expected reforms might come sooner. Many believe the police are resisting change, unwilling to give up the enormous powers they enjoy.

So Xi Jinping and China's new government could tinker with the system and leave parts of it intact, or they could opt for more far-reaching reforms. A bolder course may signal that limiting the powers of officials and police and beginning to strengthen the rule of law is a priority for the new leadership.

However, any reform will not affect the far bigger system of prison labour camps, estimated to hold millions.

In some places camps under the laojiao system are already being wound down, albeit slowly. In Yunnan in south-western China several former camps now hold only drug addicts. Dressed in identical uniforms, the addicts, undergoing detoxification treatments, march in squads. In the workshops they sit in ranks at tables making small electrical components.

'Dustbin of history'

Four years ago there were 160,000 inmates in the re-education system, according to official government statistics. By last year the number was down to 50,000 being held in 350 labour camps.

The labour camps were set up in the 1950s to silence political opponents

Many ordinary Chinese hate the system and want to see it scrapped in its entirety. One of them is Li Zhengtian, a well-known artist, philosopher and musician. He was sent for re-education in a coal mine in the 1970s. His crime? Drawing "big character posters" calling for the rule of law. He says today's China still urgently needs the rule of law.

"I refused to bow my head in submission, so they hit me, again and again," he says.

"I lay in a pool of my own blood for more than three hours. We must abolish it as soon as possible. The law should protect people's rights."

And Tang Hui, who was locked up for seeking justice for her daughter, is adamant, the camps must close for good if China is to build a just and fair society.

"Our leaders talk about social harmony, but there can be no harmony as long as the labour camp system exists," she says.

"It's brought too much pain. The only thing that stopped me from committing suicide in there was thinking about how I could get my revenge on those who sent me to the camp."

For now, at Zhuzhou and dozens of similar camps, life goes on in China's hated gulags. But the pressure for change is growing, and after Tang Hui's incarceration even China's official media have joined the chorus, saying it's time the system was "swept into the dustbin of history".