China activist daughter's fight to go to school

- Published

The brother-in-law of imprisoned dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo appeared in court this week to battle fraud charges. His family believe he is being punished for his connection to his famous relative. In other cases, it is the children of China's dissidents who appear to be paying the price for their parents' activism, reports the BBC Celia Hatton in Beijing.

Zhang Anni says she wants to be allowed a normal childhood

Zhang Anni is the 10-year-old daughter of long-time pro-democracy activist Zhang Lin.

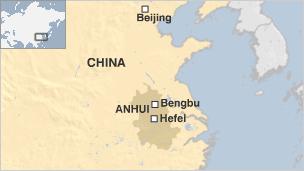

For seven weeks this year, Chinese authorities barred Anni from going to school in central Anhui province.

"Normal kids, when they are in school, they don't like school. When they are not in school, they miss school," Anni explains when asked about her ordeal.

"It's not that I want to go to school that much. I just hope to live like average, normal kids do."

Anni was sitting in her elementary school classroom in Hefei, Anhui's provincial capital, in late February when she was physically removed from the school by four unidentified men.

The men took Anni to the local police station. She sat alone in a room for three-and-a-half hours before her father joined her.

The pair were then transported back to her father's hometown of Bengbu.

"Hefei's police station has a national security director. He's pretty tough with me and he doesn't like having me in Hefei," Zhang Lin explains.

"I have different political opinions and I post on the internet a lot. That's why they want to kick me out. My daughter's situation was related to that."

Zhang Lin participated in 1989's pro-democracy protests from Hefei. Since then, he has served a total of 12 years in prisons and labour camps, most recently for "inciting state subversion", a vague charge often levelled at critics of the government.

Political dissidents across China were forced to leave their homes in major cities ahead of the parliamentary session in March, when Xi Jinping was installed as China's new president.

When Anni and her father were allowed to return to Hefei, Anni was barred from returning to school.

The men who had dragged her out of school in February had scared the other children, the school's head teacher argued.

Activists from around China and overseas protested the Hefei school's decision. An open letter from Anni to China's first lady, Peng Liyuan, circulated on the internet, asking for help.

Soon after, Bengbu's authorities allowed Anni to enrol in school, though it is very different from her original school in the provincial capital.

"The old school only has 20 students in every class, and the new school has 50," Zhang Lin says. "It's very crowded and the teachers are a bit rough."

Zhang Lin remains under house arrest in Bengbu, with limited access to the internet. Guards watch his home, only allowing him to venture out to buy food and to take his daughter to school.

Anni is also struggling to adjust to life in Bengbu.

When asked what she wants to do in the future now that she is allowed to study again, Anni pauses before answering:

"I haven't thought about it. An old saying goes, I forgot exactly what it is, but it asks you to focus on the issues right in front of your eyes.

"If you can't solve your current problems, how can you talk about the future or talk about dreams?" she asks.

"I want to do some other things like a normal kid. They are able to wake up and go to sleep early, and their parents love and care for them.

"They don't have to think about annoying things, like whether there are people who want to kidnap them."

- Published23 April 2013

- Published8 March 2013

- Published27 February 2013

- Published3 December 2012