Questions linger after deadly Sichuan quake

- Published

For many people there are still a lot of unanswered questions

In China there are people who are very difficult for the foreign media to talk to.

Those campaigning for political change are monitored and are often out of bounds. So too are the leaders of unofficial churches.

But you would not perhaps think that the parents of dead children, killed in one of the most destructive earthquakes on record, would be treated in the same way. Yet they are.

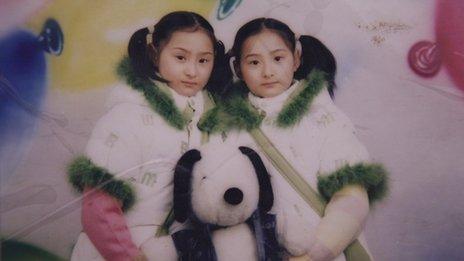

This Sunday will mark the fifth anniversary of the deaths of Zhao Yaqi and Zhao Yajia, the 15-year-old twin daughters of Zhao Deqin.

They were killed when their school building collapsed, just two of the more than 5,000 young lives taken in the same way by the Sichuan earthquake.

It struck at 14:28, when classrooms across the province were full.

'Beaten up'

To meet Ms Zhao, we had to use an unregistered mobile phone to call an intermediary. We then met that intermediary at a train station before being escorted to Ms Zhao's home.

Our interview was conducted amid the fear that it could be interrupted at any time.

"It's like being treated as a spy," she said. "I've never intended to seek trouble with the government or acted against it. I simply miss my daughters, but I've been beaten up. What kind of life are we living?"

The Sichuan earthquake left up to 90,000 people dead and millions homeless.

But it was the collapse of so many school buildings that mixed anger and recrimination into the grief.

Twins Zhao Yaqi and Zhao Yajia were among thousands of children who died

Ms Zhao says she wants a full, public investigation into whether shoddy construction was partly to blame.

These demands, as well as her claims that she has not received the promised compensation, have brought her close attention from the authorities.

And she is not alone. We exchanged messages with one mother who said her water and electricity have been cut off for more than two weeks in the run-up to this anniversary.

And in the town of Juyuan, we met a man who lost a daughter in the same school as Ms Zhao's children.

He pointed to a man standing outside his home, stationed there to watch him, he said.

'Much better'

So we decided to move on, but shortly afterwards we were intercepted by the police and taken to a government office.

They told us that if we wanted to speak to families, they would choose them for us. For an hour we tried to convince them to let us continue, but they were insistent.

The old town in Beichuan has been preserved as a memorial to those who died

"The families don't want to dwell on the past," they said. The foreign media should focus on the recovery and reconstruction.

And so our guided tour began. We were taken to see some of the hundreds of thousands of new homes that have been built.

And we were introduced to people like Tang Fuying in the town of Cui Yuehu, who seemed genuinely grateful for the help they received, regardless of the constant presence of the officials lurking in the background.

"This house is much better than the one destroyed in the earthquake," Ms Tang said. "I used to have to burn grasses to cook, but now I just turn on the gas."

That the reconstruction effort has been extensive is beyond dispute.

Millions of tonnes of concrete have been poured into the new roads and bridges and apartments, as well as 3,000 new schools.

The town of Beichuan, one of the worst affected, has been completely rebuilt a short drive away down the valley.

It is a modern, comfortable development, with residents playing ping-pong outside in the warm Sichuan evening.

Some of those affected by the disaster are still searching for answers five years on

But their old town has been preserved, left as it was after the earthquake, as a memorial.

Visitors can still see the twisted, buckled streets and the piles of rubble that used to be offices and residential tower blocks.

Some are leaning at seemingly impossible angles, and in parts where the external walls have been destroyed, you can see inside.

There is a bed and a table left in a rubble-strewn room, and a school desk on a now sloping floor, just as they were on 12 May 2008.

'Wakes in tears'

The town, under the fluttering national flag, is also a symbol of how the Communist Party would like the earthquake to be remembered, as a victory of resilience over adversity.

That it was an overwhelming force of nature is of course beyond dispute.

But the idea that human culpability may have also played a role in the collapse of so many public buildings, especially schools, is still seen as dangerously subversive.

"It is like the sky has fallen down," Zhao Deqin says. "My husband still dreams about our daughters every night and wakes up in tears."

She wants to know for certain whether anyone is responsible for their deaths.

And whatever the answer to that question, one thing is clear. Her story is one that China still does not want the world to hear.

- Published10 May 2013

- Published22 April 2013