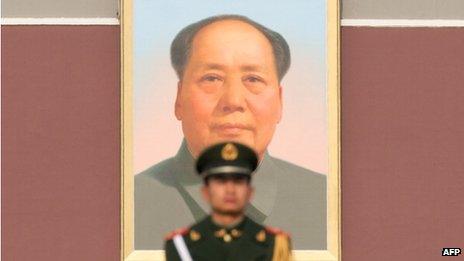

Can Xi Jinping's Mao-style clean-up campaign revive public trust?

- Published

Mao Zedong's legacy still has a huge influence on Chinese politics today

On a sunny Saturday morning in Beijing's Tuanjiehu neighbourhood park, a few hundred retirees have gathered to sing songs from their childhood. Many of the lyrics celebrate China's Communist Party founder, Mao Zedong.

"The mountain and the river are smiling," they croon. "Chairman Mao's thoughts are guiding us."

The people here yearn for more than the music of the Mao era; they miss the days when China's Communist Party was known for its honesty.

"Mao shot corrupt officials. Now, there are so many corrupt officials but no one is shot," one man complains.

"This government isn't serious about tackling this problem."

'Shameless masses'

There's a widespread perception on the streets of Beijing and across the country that China's leaders are out of touch with Chinese society.

President Xi Jinping is trying to change that by reviving a Mao-era rectification campaign, urging senior officials to clean up the dirty world of Chinese politics.

Xi Jinping has vowed to crack down on corruption in the Communist Party

It's a mammoth task. New scandals surface almost on a weekly basis, emphasising the gulf between the party and the people.

A recent case encapsulates the problem: Liang Wenyong, the Communist Party boss of Gushanzi, a farming town in Hebei province, was caught on tape at a lavish banquet.

As he picked a variety of delicacies in front of him, including a whole lobster, Mr Liang gave his unvarnished views on the Chinese masses.

"Their bowls are filled with rice, their mouths are filled with pork, but after they finish their meals, they criticise the government," he laughed.

"The Chinese masses are shameless and you don't need to respect them."

The leaked video quickly prompted more than 9,000 angry comments on Weibo, China's version of Twitter.

'Self confessions'

Unsurprisingly, Liang Wenyong was fired. But in a twist typical of the new clean-up campaign, officials in Gushanzi were also ordered to study Xi Jinping's teachings.

China's newscasts regularly quote Xi Jinping's internal party speeches, containing phrases that copy Mao's folksy style.

In April, China's state media headlined Mr Xi's speech to senior officials, urging them to "look in the mirror, straighten your uniform, take a bath and seek a doctor".

Party elites have been ordered to study Communist history and to spend more time with regular people.

Xi Jinping has also revived the use of "self confessions", another Mao-era ritual.

On a recent trip to Hebei province, Xi Jinping attended a meeting of provincial officials in which they admitted to their own failings and, in a nod to China's turbulent past, also placed blame on their colleagues.

Ultimately, this campaign hopes to shore up the party's legitimacy, so it retains power, explains David Kelly, the founder of China Policy, a Beijing research firm.

"If you think the officials believe in the doctrine, then they've got more legitimacy, and you'll follow them and you'll obey them," explains Mr Kelly.

Disgraced politician Bo Xilai encouraged the singing of Mao-era 'red songs'

"But if you think those officials themselves don't believe the doctrine, it's like the situation in the Catholic church, if you think the priests themselves don't believe the gospel. It's what you think the hierarchy thinks."

If this all sounds familiar, that's because this political strategy has been used before by Bo Xilai - the former top politician jailed for corruption, bribery and abuse of power.

"Xi Jinping has sacked the man, put the man on trial and purged the man, but adopted the style, " Mr Kelly explains.

Activists arrested

The style, it seems, dictates that only the campaign's leader can decide what needs to be cleaned up, so activists pushing for greater government accountability are under fire too.

Xu Zhiyong is known for his anti-corruption and human rights campaigns

An unknown number - likely to be hundreds - of bloggers, academics and dissidents have been detained: people like Xu Zhiyong, a respected former law professor arrested in July.

In secret video smuggled out of prison, Mr Xu appears in handcuffs, looking exhausted. He is a tireless advocate for citizens' rights, including a demand for officials to make their assets public.

"No matter how rotten and ridiculous this society is," he tells the camera, "this country needs a group of brave citizens to stand up."

Mr Xu's lawyer, Si Weizhang, sees a direct connection between his client's arrest and Xi Jinping's efforts to reinforce his hold on power.

"The party's anti-corruption campaign is meant to strengthen control over the party," he explains. "Xu Zhiyong's arrest is aimed at strengthening control over society.

Mr Si is desperately trying to secure his client's release from prison. Xu Zhiyong's wife is six months pregnant with their first child, he explains, and she needs her husband to come home, he says.

Back in Tuanjiehu park, one group of citizens continues to enjoy the songs of a bygone era. Almost everyone here questions whether Xi Jinping can draw any lessons from Mao when tackling the party's current problems.

"Even if Mao came alive and sat up, it would be impossible even for him to do the things he did before. We're in a different time," one man shrugs.

Xi Jinping is contending with a different time, and a host of modern problems.

China's current leader is clearly copying Mao Zedong's style, but he'll have to create his own solutions to address the rampant corruption and disillusionment that was inconceivable in China's Communist heyday.

- Published19 September 2013

- Published7 September 2013

- Published4 September 2013

- Published8 August 2013

- Published17 July 2013