China sex trade infiltrates international hotels

- Published

John Sudworth: "One of them tells me she's 20 years old, and has sex with up to three clients a day"

Prostitution is illegal in China, but the BBC has uncovered evidence of organised prostitution at independently run spas located inside a number of well known, Western-brand hotels, as John Sudworth reports for Newsnight.

The Kempinski Hotel chain calls itself Europe's oldest luxury hotel group. Founded in Germany, now based in Switzerland, it operates more than 70 five-star hotels around the world, including one in the city of Qingdao on China's east coast.

But following the signs to the spa in the basement, along a gloomy corridor, we found little luxury, just a small room from which more than 10 women are bought and sold for sex.

"Do you need them just once, or do you want them to stay overnight?" we were asked by the man on duty.

Staff working out of a third-party run business inside this building said they could provide up to 10 women for sex

He made it clear that the business was independently run as he could not, he said, offer us an official hotel receipt. But there appeared to be little secrecy about what was on offer.

One of the prostitutes told me that she was 20 years old, had sex with up to three clients a day, and was allowed to keep just 40% of the fee charged.

It is a stark illustration of just how easily reputable foreign businesses in China can become tangled up in vice and criminality.

China's communists once claimed to have eradicated prostitution. Whether they ever succeeded is debatable, although for a period, it was driven from public view.

Today, it is safe to say, the battle has truly been lost.

On paper at least, the ideological sanctimony is undiminished and prostitution remains illegal, but in practice the party rules over a country in which sex is bought and sold on an industrial scale.

Household names

There are an estimated four to six million sex workers in China, hiding in plain sight in the barbers' shops, massage parlours and karaoke bars that can be found pretty much everywhere.

So the allegation that prostitution is thriving inside some hotels in China will not be surprising to anyone with even a passing acquaintance of the travel and tourism industry here.

But our investigation shows for the first time just how far pimps and prostitutes have moved into the international hotel industry, apparently without its knowledge.

With very little effort, we have found the sex trade operating from inside hotels that are household names in Europe and America, seemingly with little fear of detection.

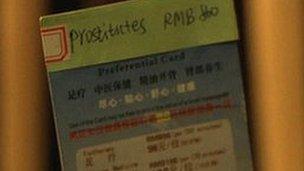

At the spa operating in the Ramada Zhengzhou a leaflet was marked with the price for a prostitute

We called dozens of international hotels in China and asked to be put through to their spas.

A BBC colleague, posing as a personal assistant, told the spa receptionists that she was setting up a business meeting for potential clients who expected sex to be available in the chosen venue.

In around 7% of those she spoke to, in cities as far afield as Nanjing and Qingdao on China's east coast and the inland cities of Xian and Zhengzhou, we discovered that prostitution is very easy to arrange.

Using the results of that telephone survey, we then visited some of those hotels and, using the same cover story, filmed what we found on hidden camera.

In Qingdao, as well as what we found in the Kempinski Hotel we found sex on sale in the Intercontinental, part of the British-based hotel chain.

The signs in the spa on the second floor make it very clear that it is not run by the hotel, but is under independent management, and here legitimate massage is clearly the mainstay of the business.

But the spa staff showed little hesitation in telling us that sex could be supplied to those who ask for it. The prostitute herself told us that the bill for her services could be settled at checkout through the hotel main-desk.

Hotel denials

Both the Intercontinental and the Kempinski deny any knowledge of the prostitution we have found.

In a statement, the Intercontinental Hotels Group told us: "Prostitution is strictly prohibited" in all of its hotels, and that third-party run businesses, like the spa, have a "contractual obligation" to abide by that policy.

"Hotel staff have not knowingly been involved in processing bills for prostitution," it said.

The Intercontinental Hotel has now closed the spa.

A prostitute at the Intercontinental Hotel, Qingdao claimed her services could be paid for via the hotel

The Kempinski Hotel issued a statement saying: "While a spa was originally planned for the hotel, hence the signage in the elevators, the actual facility was never approved nor opened or operated by Kempinski Hotels."

The hotel, it said, is connected to a third-party business through a basement passageway that "cannot be closed off for safety reasons".

We asked the Kempinski why it was that when we called the hotel main desk, asking to be transferred to the massage centre, staff put us straight through to the pimp in the basement.

"Regarding the phone calls I'm afraid that there is no way for us to verify the calls and/or if indeed they were redirected," was the written reply.

The Kempinski group had already decided to pull out of the hotel in Qingdao before our investigation. They will cease to manage it from 15 November, a sign that just a year after it opened something has gone badly wrong.

The third hotel we visited was the Ramada Plaza in the city of Zhengzhou.

Once again, we followed the signs to the third-party-run spa, which was on the sixth floor. Passing a somewhat suggestive poster of a woman at the entrance, we found a massage centre that we were told was available for the use of male customers only.

The man on the reception desk told us that sex could be provided and that more than 20 women worked there. And he handed us a small leaflet on the top of which, handwritten in English, were the words, "Prostitutes 800Rmb" - about £85.

Female guests' warning

In response to our findings the Wyndham Hotel Group, which owns the Ramada brand, said it was looking into the matter and issued a statement which said: "Please know that we are a family-oriented company."

The company told us that while most hotels are run as franchises, "independently owned and operated", they are required to comply with the law and that Wyndham is providing training to help employees "identify and report human exploitation and abuse activities".

But it added, "As long as there are people profiting from tragic practices, we believe no member of the travel and tourism industry can ever guarantee these events will not occur in the future."

Shaun Rein says the Chinese government is likely to crackdown on foreign companies

Few customers who visit the spa in the Ramada Zhengzhou would be left in much doubt about what is on offer there.

Indeed, a group of female travellers who stayed at the hotel earlier this year raised their suspicions in a review posted on the TripAdvisor website. "If you are a woman, don't come and stay in this hotel," it urges readers.

While prostitution might be easy to find in China, prostitutes continue to face danger not just from clients but the police too.

Sophie Richardson is the China Director of Human Rights Watch, which recently called for the Chinese government to remove the criminal sanctions in force against sex workers.

"We've documented torture and other kinds of physical abuses of sex workers, including rape, both by clients and by police," she told the BBC. "Anybody who understands what's at stake here and how vulnerable sex workers can be to these kinds of abuses would want to step up."

Three years ago, one foreign-run hotel was raided and closed by the Chinese police because a karaoke bar in the basement was linked to prostitution.

But now our investigation shows that the widespread use of third-party-run spas means that the sex trade has gained a much firmer foothold than the industry itself appears to realise.

Government scrutiny

Shaun Rein, managing director of China Market Research Group, advises foreign companies operating in China. He said that there is more that some hotels could be doing to keep the sex trade away from their doors.

"The companies should be negotiating with the landlords or the owners of the properties from day one," he said. "They should say that if we're going to run a spa, it can be owned by a third party, but it needs to be managed by our own employees, and we also have to be in charge of the hours, so it closes at nine pm, rather than later."

Mr Rein said that now more than ever, foreign companies in China should be striving to stay clean.

"There's a definite reputational risk for the brands to have hookers in the hotels, especially from the government side because they're going to crack down and go after foreign brands to show the country that they are adhering to the laws," he said. "It's much easier to crack down on a foreign brand than a local one."

A few months ago the British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) found itself on the receiving end of just such a crackdown, accused of paying bribes to boost sales.

It was forced to admit that some of its employees did appear to have broken the law. But many observers wondered why GSK was being singled out when corruption is widely alleged to be endemic in China's domestic pharmaceutical industry.

Now our investigation suggests that the international hotel trade is at least running the risk of handing the government another political opportunity to look tough on foreign business.

- Published14 May 2013