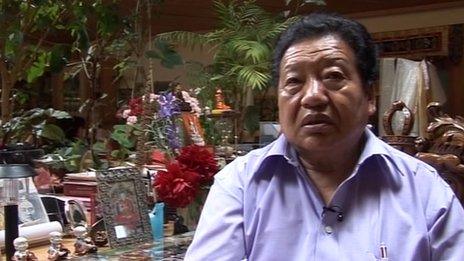

Akong Rinpoche: Tibetan monk achieved feat of Chinese approval

- Published

Akong Rinpoche fled Tibet following a failed uprising against Chinese rule in 1959

Without fuss and with little ceremony, an elderly, high-ranking Tibetan monk was cremated last week at the monastery in Tibet that he first entered when he was just four.

Akong Rinpoche had been stabbed to death. His followers had proposed an elaborate cremation, but the Chinese authorities - always on their guard against shows of Tibetan nationalism - wanted it over and done with as quickly as possible.

The event was hardly noticed in the outside world, perhaps a fitting end to a monk whose work over the last few decades has attracted little attention outside his group of devoted followers.

But Akong Rinpoche - who established a monastery in Scotland - was a unique individual.

He helped bring Tibetan Buddhism to the West and achieved something few Tibetan exiles manage to pull off - make friends among China's top leaders.

"He was the consummate diplomat and managed, even in death, to retain a silence about politics," said the director of modern Tibetan studies at New York's Columbia University, Robert Barnett, who met Akong Rinpoche and has followed his career.

Boot leather soup

Through his charity, ROKPA, the monk set up more than 100 health, education and cultural projects in Tibet, all with the support of the Chinese authorities who govern the region.

He went back every year to hand out money, basing himself in a flat in the city of Chengdu. It was in that apartment he was stabbed to death in an argument with three fellow Tibetans. Two others, including Akong Rinpoche's nephew, were also killed.

One of the suspects, who have all been taken into custody, was Thubten Kunsal. He had previous spent five years at Akong Rincpoche's monastery, Samye Ling near Lockerbie, making religious statues. He thought Akong Rinpoche owed him money.

He must have known the monk from Scotland was in China to distribute funds. "Akong Rinpoche died defending those funds," read a statement from the Lockerbie monastery.

Akong Rinpoche is an honorary title. The name on his British passport was Shetrup Akong Tarap.

He was born in Tibet in 1939 and quickly identified as the reincarnation of the abbot of the monastery Dolma Lhakang, in the eastern part of the region.

He was enthroned in the monastery at just four years old and then began his spiritual education.

But it was a turbulent time in Tibet. The Chinese communists invaded in 1950 and began to exert their control. There was a failed uprising in 1959 after which many leading Tibetans, including Akong Rinpoche, fled.

He left with a party of 300, but only 13 of them made it to India after a 10-month journey. Along the way, they had to boil the leather from their boots and bags to make soup.

David Bowie visit

He did not stay long in India. In 1963 a patron helped him go to Oxford in Britain to study English. But he was not a great student and ended up working as a hospital orderly to support the studies of a fellow Tibetan, who went on to become another revered monk known as Trungpa Rinpoche.

It was a time of growing interest in Tibetan Buddhism and the two set up the Samye Long monastery in a rat-infested former hunting lodge.

In the early days, Trungpa Rinpoche seemed to be the driving force, but after a road accident his style of teaching changed, and might not have been appreciated back in Tibet.

There were wild parties and the monastery started attracting a smattering of rock starts, including David Bowie. Trungpa Rinpoche eventually married one of his students and then moved to America.

That left Akong Rinpoche, who slowly established himself as a teacher and health expert.

Akong Rinpoche said the countryside around the Samye Ling monastery in Scotland reminded him of Tibet

The reverence in which he was held could be seen a few days after his death at Samye Ling, where nuns, students and visitors mingled around the monastery's courtyards and walkways.

Many of them were visibly upset and embraced each other for comfort. Worshippers are in the middle of 49 days of prayers for their former master.

"It helps us deal with this terrible, tragic event," said Gelongma Tsultrim Zangmo, a monastery nun who was Akong Rinpoche's personal assistant for 25 years, but first met him nearly half-a-century ago.

But the founder of Samye Ling was not liked by everyone.

Some exiled Tibetans thought he had become too close to the Chinese government, who have a hardline policy in Tibet, in order to keep his projects there up and running.

In one photograph published in 2006 by the Chinese state-run news agency Xinhua, a smiling Akong Rinpoche is seen in London greeting Jia Qinglin, then a member of the standing committee of the Chinese Communist Party's politburo.

Talking of Tibetans willing to meet China's leaders, Thubten Samdup, the Dalai Lama's representative in London, said: "Sometimes perhaps they go a bit too far - even attending Chinese embassy parties. It's almost like endorsing what (the Chinese) are doing in Tibet."

He said some people thought Akong Rinpoche was a "traitor".

That is a charge vehemently denied at Samye Ling. "He would not take any political stance whatsoever. It was because of his impartiality that he was able to function in the way that he did," said Akong Rinpoche's assistant.

Robert Barnett, from Columbia University, agrees that the Tibetan monk was an experienced diplomat, skilled in the art of avoiding political statements.

"He managed to say very little and both sides respected him for that," said Professor Barnett.

At a time of poor relations between China's leaders and Tibetans, both inside and outside the region, perhaps Akong Rinpoche's legacy was to show that the two sides can work together.

"I'm not sure anyone else will have the skills and patience to carry this out again, " added the professor.

- Published11 October 2013

- Published8 October 2013

- Published7 January