Xi Jinping's urban gamble

- Published

China's leaders are committed to rapid urbanisation - but will it bring stability?

A year into power, if there is one thing that becomes clearer about the Xi Jinping leadership of the Communist Party of China, it is that it understands the value of political symbolism.

One of the first places Mr Xi visited after becoming party secretary last November was Shenzhen, hallowed turf of the Reform and Opening up Process since 1978, and amongst the first and most dynamic Special Economic Zones.

The meeting at which the ideological innovations were reached which made the acceptance of foreign capital and a market in China possible were at Jingxi Hotel in Beijing in December 1978.

Over three and a half decades later, the approximately 400 super-elite of the party met in the same place again. This in itself created expectations that historic events were about to occur.

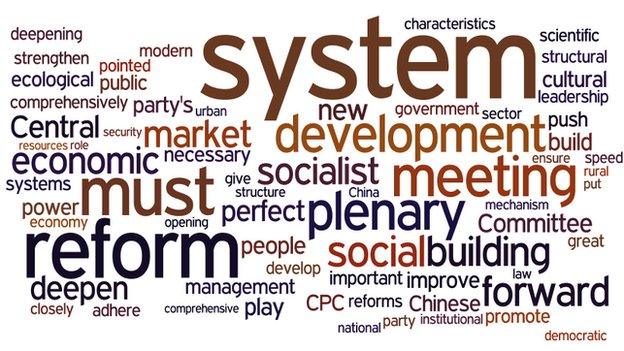

The theme of deepening reform is reflected in a word cloud of the final communique

The communique from the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress issued on 12 November after the three-day meeting should put paid to the notion that this leadership is about to undertake the same dramatic reverse that the 1978 event achieved.

Times are different. The simple fact is that a misstep now would be far more costly than back then, when the country was emerging exhausted from late Maoism and had to do something radical to energise its economy.

Now, China is a global economy, and one with everything to play for in the coming decades. Its challenge this time is simply to, in the words of Premier Li Keqiang, unlock new sources of growth within itself.

There is no question of it, at the moment at least, needing to fundamentally change track. The mechanism to achieve growth will be improving and perfecting the market, and liberalising new areas where growth might come. That is the most powerful message from this plenum.

Challenging the fundamental principles of the Reform and Opening Up era was never going to happen. The primacy of the party is stated with crystal clarity in the plenum report. Its key role in society remains paramount. The need for internal unity and collective leadership remains as prized as it was in the Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao era.

The objective is still, through the ideological instruments of Deng Xiaoping theory and Socialism with Chinese characteristics, to achieve "the primary state of socialism". That will take, in the words of the communique, "many years".

Rural mobility

There are more explicit references to the creation of a national security coordination body.

This seems to be the Hu and Wen fixation with "pro-stability" measures in another guise, with some attempt to now finally co-ordinate and streamline decision making in this area, particularly as there is no one on the Standing Committee of the current Politburo with specific responsibility for security issues as there was in the previous one.

The premium this leadership places on stability remains high, and the car explosion in Tiananmen in early November along with the home-made bomb attack in Taiyuan at the same time will only highlight to this leadership that relaxing on the issue is not an option.

Politburo member Yu Zhengsheng referred before the plenum to deeper new reforms being on the horizon. It is clear now that this referred to introducing a more flexible system whereby rural residents can move to urban areas, find work there, settle there, have access to social welfare and, perhaps most critically of all, educate their children.

The government in the last few months has referred heavily to the need to accelerate urbanisation, and having a framework within which to enfranchise and give incentives to rural dwellers so that they can move is important.

Implementation however remains key here, so while the statement of intent is strong enough, the question will be how to convince provincial governments across China that they can carry the costs of a new wave of citizens that they somehow have to provide social goods for.

There is no explicit mention of whether provinces will therefore be given wider tax raising powers, though this would seem a natural corollary to having a new influx of residents.

Urban gamble

On economic reform, the strongest theme is that of developing a finance market. Here too we see the intellectual influence of Li Keqiang, the person most closely associated with the establishment in October of a Free Trade Zone in Shanghai, a place where China's capital account might be liberalised and the trading of Chinese yuan accelerated.

Finance will be a critical sector for this leadership, one of the key means to delivering a high service component in the economy, and of creating a high value added economy.

This plenum gives a framework, which confirms some of the themes that have already emerged from this leadership. No quick ideological or political change, a continuation on emphasising people's material well-being and trying to achieve strong growth, with the key drive being to achieve a high level of urbanisation before 2020.

The plenum took place behind closed doors in Beijing

If there is one bold feature of this plan it is that almost everything is staked on an urban China being one where the current problems of achieving growth, answering some of the sustainability issues, and addressing inequality will become more soluble.

This is a big gamble, because the rate at which China evidently plans to become urban is faster than any other society has tried.

There are vast issues about how social cohesion will be achieved, and what sort of social and political structures might finally come from this to achieve the sort of harmonious society that the previous leadership spoke so much about.

Kerry Brown is professor of Chinese politics at the University of Sydney, team leader of the Europe China Research and Advice Network (ECRAN) funded by the European Union, and an Associate Fellow of the Asia Programme at Chatham House.

- Published13 November 2013

- Published12 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

- Published22 September 2015