Morecambe Bay: Families left behind by cocklepicker tragedy

- Published

The BBC speaks to some of the families left behind

On the 10th anniversary of the disaster in north-west England's Morecambe Bay that claimed the lives of 23 migrant workers, John Sudworth goes to meet one of the families left behind in China.

Cao Chengle, 72, lives in a ramshackle home surrounded by reminders that many migrant workers from his village have been much luckier than his son.

"Look at the other people," he tells me. "They've all made it and have built big houses. But we're living like cavemen."

In 2004, as a BBC reporter based in London, I was sent to Morecambe Bay to cover the aftermath of the death of 23 Chinese workers cut off and drowned by the rising tide as they collected cockles from the sand.

I interviewed the lifeboatmen who pulled the dead bodies from the water that night. I spoke to people still busy raking up shellfish, some of them foreign migrants. And I wondered, of course, about those lost lives.

Who were they? What kind of homes had they left behind?

Now 10 years later and 6,000 miles (10,000km) from Morecambe, Cao Chengle is answering those questions for me in the village of Cangxi in China's eastern Fujian province.

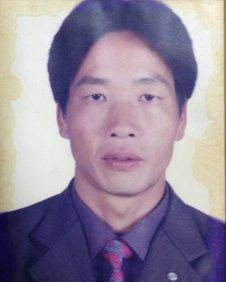

Cao Chengle said his son, Cao Chaukun, would have been able to financially support his family

Unregistered lives

In late 2003, his son Cao Chaokun, then 35 years old, paid a gang of people-smugglers to take him to Europe.

A little more than a month later, he found himself working in England, on a bracing cold beach, along with a large group of fellow Chinese migrants.

It was hard, poorly paid work in a landscape which, to the untrained eye, could appear dangerously, deceptively serene.

On the night of 5 February 2004, they ventured far out on to the sandbanks in the dark, with the tide already beginning to turn.

A few hours later, they were marooned and then engulfed as the waters swept in around them.

The recordings of the desperate phone calls made in broken English to the emergency services that night make chilling listening.

It is the sound of 23 unregistered, undocumented lives slipping away beyond the reach of a society they'd never been part of.

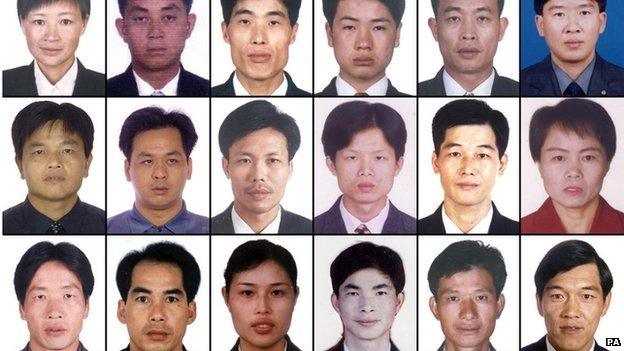

The Chinese workers drowned in 2004 as they collected cockles from sand banks cut off by rising tides

For the British public, the disaster offered a glimpse into the risks and abuses inherent in the illegal economy.

It played into the already charged immigration debate and led directly to a new law regulating the agents who employ groups of vulnerable agricultural workers.

But today, for the families left behind in China, it continues to mean just one thing; hardship.

"It would be much better if he was still here," Cao Chaokun's father tells me.

"He'd be making money, he'd be able to support his family. Now the burden is on us, two people in their seventies, and our daughter-in-law."

Desire to do better

Standing on the sands in Morecambe back in 2004, I remember speculating about the kind of desperation that would drive people to come so far at such a cost.

On reflection though, standing now in one of the villages they left behind, that question somehow seems to have missed the real point.

There is certainly poverty in eastern China, but there is no starvation or serious deprivation.

In fact, the most striking sight is that of the big houses that Cao Chaokun's father so badly craves. They're everywhere.

Giant, ostentatious, multi-storey piles that at first glance you could easily mistake for apartment blocks until you realise they are almost all single family homes.

And many of them have been built with money earned by family members working overseas.

At this house, a husband away in Australia doing interior decoration; next door, a son in America working in a restaurant; over the road, a brother in South Africa importing and selling Chinese-made goods.

The scene is repeated in every village we drive through.

Fujian provides a stark illustration of what motivates economic migrants everywhere.

Not always a flight from squalid desperation but often just a simple desire to do better.

Cao Xianyong, son of Cao Chaukun, wants to work overseas someday

A European Union-funded study, external published last year suggests that since 1980, from Fujian alone, more than one million Chinese migrants have gone overseas in search of that better life.

Up to half of them, according to Chinese government research, may have gone through illegal channels.

When Cao Chaokun drowned at Morecambe, his son, Cao Xianyong was just six years old. Today, the teenager still lives in the village of Cangxi and shares a humble one-room home with his mother and sister. It is surrounded on every side by the taller, newer buildings.

And despite what happened to his father, he is keen to follow in his footsteps.

"When I'm older I want to make money to save my mother from working too hard," he tells me.

"I want to go abroad. I want to go the US and start from the beginning, take it slowly and when I have enough money, open a restaurant."

'Mother don't cry'

Cao Chaokun paid people-smugglers to take him to Europe

The Cangxi village officials introduce me to another mother and father who, they tell me, also lost a son in England.

It appears to be a welcome and unexpected chance to hear, first-hand, about the effects of the Morecambe tragedy on another family and they agree to be interviewed.

"The last words my son said to me were 'mother don't cry'," 69-year-old Chen Yuying tells me. "He said he'd only be there for a few years.'"

But suddenly my translator is looking baffled and I can sense her searching for clarification as the conversation continues in a mixture of Mandarin and the Fujianese dialect. Then there's an awkward pause.

"Their son didn't die at Morecambe," she tells me. "He died a few years earlier, in June 2000."

Cao Xiangping was one of the 58 Chinese migrants found suffocated to death in the back of a lorry at the port of Dover.

His parents, of course, had no idea that we'd come to Cangxi to focus only on one tragedy and for the somewhat superficial purpose of marking its anniversary.

But that two families, living a stone's throw from each other in one village in China, should suffer the same loss four years apart is not just a coincidence.

It underlines the fact that so many people from this part of China have gone abroad and the risks that they take in doing so.

The same EU-funded study cited above suggests that illegal Chinese migration, particularly people-smuggling, is now in decline.

Mainland migrants

The British public raised money for families of those who died in Morecambe Bay

Since 2004, the number of alternative, legal and much safer ways of leaving China has increased, including a big jump in Chinese student numbers.

The destinations of choice appear to be changing too.

In Fujian, people tell us that back in 2004, the UK was one of the most popular destinations.

Today, they say few people want to go there, heading instead for what they see as the better economic opportunities on offer in Australia or America.

And the statistics appear to confirm that trend. Over the 10 years prior to 2008, the UK population of migrants from mainland China, both legal and illegal, was growing at an average of 35,000 a year.

But since 2008, when Britain's economic boom ground to a halt, it has slowed to just 10,000 a year - although it should be noted that these figures are broad estimates with a significant margin of error.

If nothing else, they suggest that while tougher controls and tighter borders are easy political promises to make, in the end, a recession might be a more effective tool in curbing illegal immigration.

In one regard, the families of the Morecambe Bay cockle pickers have been lucky.

The money to pay the human traffickers was borrowed, around £20,000 pounds ($33,000) each, leaving their surviving relatives with the large debts.

These have since been covered by a generous charitable donation, more than half a million pounds in total, raised by the British public.

But in Fujian, we learned of two other children whose father died at Morecambe already working abroad, one in Australia, the other in Zimbabwe.

Those who haven't gone already are more than likely to be dreaming about doing the same.

- Published5 February 2014

- Published11 November 2013

- Published20 October 2010