Sweeping change across China's Inner Mongolia

- Published

Extraction of gas and coal are depriving local herdsman of their traditional land rights

Traditional music floated across the freezing grasslands that stretched far into the distance.

Inner Mongolia is China's strategic frontier and home to its Mongolian ethnic minority.

They are the descendants of the Mongol warrior, Genghis Khan, who on horseback eight centuries ago swept across much of Asia, creating one of the world's greatest empires.

Today, the Mongolians still celebrate their traditions at nadaams - or traditional games.

Hundreds watched as a train of camels swept into a small stadium on the grasslands, their hooves kicking up the snow. Some of the animals pulled wooden sleighs with children sitting in them.

They were ridden by Mongolian herdsmen wearing traditional blue, green and red lambskin outfits to protect them from the bitter winter cold.

Mongolians are descendants of the Mongol warrior, Genghis Khan, who created an empire

The nomadic way of life is fast disappearing in Mongolia

'Nation will vanish'

Throughout the day, the crowd watched camel racing, archery on horseback, and traditional wrestling.

But most of this was for show. The nomadic way of life is fast disappearing.

Many of the Mongolians arrived at the event in fancy four-wheel drive vehicles.

Looming in the background, smoke from chimney stacks curled up into the blue sky - there is no escaping the modern world here.

A resource boom is bringing sweeping change to the region.

"Mining is destroying our environment," Tsogjavkhlan, a university student, told me.

"Maybe in the future we won't have a place to live like traditional Mongolians. Our nation will vanish - the Mongolians will vanish."

Occupying 12% of the country's land mass, Inner Mongolia is rich in resources - coal, gas, rare earth metals - which are being mined to fuel China's breakneck economic growth.

The region now accounts for a quarter of domestic coal production.

But the huge mining projects have scarred the landscape and brought pollution to a once pristine region. Mongols say that mining, along with desertification, is ruining their grasslands.

Chinese soldiers line up to march into the arena of the Winter Naadam Games in Inner Mongolia's East Ujimqin Banner. Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region in northern China with a majority population of Han Chinese and a substantial number of ethnic Mongol minorities.

The Naadam Games is a traditional Mongol festival for sports like wrestling and archery. This one held in winter features a camel race. The Mongolian camels are usually used to herd in the winter, as their double humps allow them to go longer without food and they walk more easily on the snow than horses.

As part of the opening ceremony, contestants hold the Mongolian white hada, or traditional ceremonial silk, and silver bowl. Offering the hada to guests is a token of auspicious blessings in the Mongolian culture and in other regions like Tibet or Qinghai.

A Chinese Mongol woman waits in the line to join others in the games arena. Like many, she wears a lambskin hat to protect herself from the extremely cold weather. In the winter, the temperature could be as low as -30C (-22F) in Inner Mongolia.

Chinese Mongol girls wrestle with each other before the games start. Mongolian wrestling, or bokh, is one of the most important elements of the Mongolian culture. It requires strength and balance, and Mongolian men take pride in winning a match.

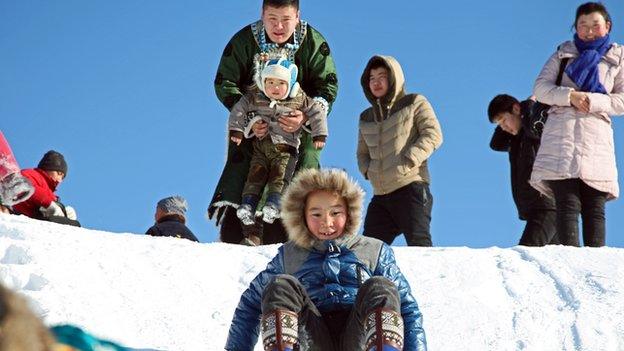

Chinese Mongol children slide down a snowy slope next to the winter Naadam Games venue. On the top of the slope, a father wearing traditional Buryat clothes - made of lambskin and stitched with colourful embroidery - gets ready to put his son in position for the slide.

A Chinese Mongol walks with his horse before the games start. He wears a traditional Mongolian outfit made of lambskin with a green belt around his waist. He carries a herding whip, which Mongol herders use to herd livestock when riding horses, on his shoulders.

Chinese Mongols in their finest winter clothes pose while on a wooden Mongolian horse sledge. The horse sledge race is one of the competitions at the Winter Naadam Games.

'They're lost'

The unprecedented mining boom has also brought a wave of Han Chinese migration to the region.

Mongolians who have populated the region for centuries are now just 20% of the population. Some Mongolians say they are missing out on the lucrative boom.

They also worry that the constant migration is diluting their culture, language and traditions.

There were rare protests in several cities across the region in 2011. They were triggered by the death of a herdsman who was protesting against a mining project.

Human rights groups say the demonstrations highlighted the discord in the region and the failure of China's policies towards national minorities.

Beijing stresses that economic development in the region has improved the lives of millions.

And many Mongols welcome the opportunities that come with development. Life is now far easier in the towns and the cities than the harsh realities of the grasslands and life in traditional tents.

One female student at the games said she was studying Food Science and Technology at university.

"Not many ethnic Mongolians study this subject," she told me. "I'm living my dream."

An hour's drive away from the winter games, we met a herdsman. Naranmandura tends his 400 sheep, 10 cows and four horses on the vast grasslands.

.jpg)

Technology, which is now making its presence felt in the region, is changing some traditions

It is the only life he has known. But technology is now replacing tradition. The 45-year-old uses a motorbike - and not a horse - to herd his sheep.

His two sons are successful Mongolian wrestlers - both of them now live in the city.

"When I was growing up here it wasn't easy," Naranmandura said.

"We only had one set clothes for all the seasons. Now children have a good life. But they don't know their culture - they're lost like a tiny boat on the sea."

Almost crying, Naranmandura said that when he died, he wanted his ashes to be scattered on his beloved grasslands.

Like many of his generation he has a deep respect for Mongol traditions. But he is torn by the demands of a different age that are bringing sweeping change to this region.

- Published24 October 2011

- Published8 June 2011

- Published31 May 2011

- Published30 May 2011