GlaxoSmithKline's China scandal: A cautionary tale?

- Published

GSK has apologised to the Chinese authorities over the bribery scandal

To observers of China's contemporary business culture it will come as no great surprise that the latest twist in GlaxoSmithKline's China crisis is a sex tape.

The secret filming of business, political and love rivals in intimate situations is now commonplace in China and motivations range from whistle-blowing to blackmail or revenge.

In GSK's case, the tape was sent as an email attachment to senior executives at corporate headquarters in London. It shows the firm's China boss Mark Reilly in his Shanghai apartment with his girlfriend and was filmed without Mr Reilly's knowledge or consent.

I've talked to a number of people from different vantage points close to the GSK story and none of them are clear who sent the tape in March 2013.

But this is just one unknown among many.

'Underground rivalry'

Almost a year after the Chinese police went public with their allegations of massive bribery at GSK, two British citizens have disappeared into the Chinese justice system, their whereabouts unknown, charges unconfirmed and trial dates uncertain, while many of those most closely involved are still struggling to understand exactly what happened and why.

In the beginning was the sex tape?

Not quite. In the beginning was internal politics at GSK China.

Chinese workplaces are just as political as those anywhere else in the world, some would argue more so because the value placed on outward harmony in Chinese culture drives the rivalry underground.

"It's a chronic refrain that this or that person's up to no good," one western lawyer told me.

The politics in a multinational's China operation can be especially insidious when there's a thin layer of western management attempting to operate according to principles which have limited purchase in the Chinese business culture beneath.

Could cultural differences have contributed to GSK's problems?

When their problems blew up, GSK had three non-Chinese staff in their China management team.

Set the personal politics and clashing business cultures against a pharmaceuticals sector with explosive growth and a healthcare industry where bribery was endemic.

Add a GSK China boss in Mark Reilly who felt, according to one of those who knew him, "under pressure to achieve stellar sales targets", who did not speak Chinese and who was described to me by others as "out of his depth" and "an innocent abroad".

Now imagine that person trying to manage a workforce of 8,000 locals in the business climate outlined above.

That's enough context, now let's turn to what we know about what happened.

'China Inc'

Throughout 2012 there had been a stream of anonymous emails to Chinese regulators alleging bribery authorised by senior staff at GSK.

Several sources outside the company have told me that the government relations manager Vivien Shi was suspected. She has denied that she had any part in these emails or any other whistle-blowing relating to bribery at GSK.

What we do know is that at the end of 2012, Vivien Shi left the firm. In January and February anonymous emails began to arrive at GSK HQ in London. And in March came the video of Mark Reilly and his Chinese girlfriend.

As this drama was unfolding inside GSK China, another game was being played out at the political level… or "China Inc" as some describe the single-minded operation at the top of the one-party state.

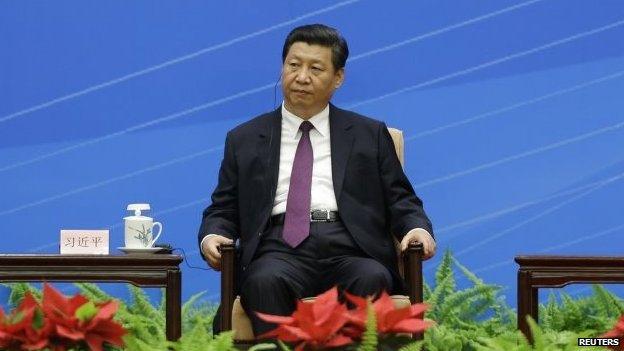

In November 2012 Xi Jinping became China's Communist Party leader and soon launched an anti-corruption campaign, with the staggering malpractice in healthcare as one of the targets in his sights.

Xi Jinping launched a major anti-corruption campaign after he took office

The elevation of a new Party leader is a vital inflection point in the way China is run. All western business veterans I've talked to here say outsiders should play by the rules all the time, no matter the temptations to do otherwise.

And it is especially important to play by the rules when the rules are changing and all the insiders are tense.

James McGregor of APCO consultants says: "Part of it, I think, is there are members of the bureaucracy trying to justify their existence at a time where China's looking to reform the bureaucracy.

"And these guys might be trying to show that they're tough and can be regulators."

Treading on toes?

So at the moment in March 2013 when the sex tape arrived in GSK headquarters in London, Xi Jinping was settling in behind his desk at Party headquarters and the entire Chinese bureaucracy was working out how to demonstrate alacrity in doing his bidding.

Ironically, at GSK China headquarters in Shanghai the company had already come to the conclusion that it had a problem with a high turnover of hungry young recruits who didn't necessarily think ethics first. Investigations were under way and tighter compliance systems being put into place.

But after the sex tape, things took a fateful turn.

To try to work out where the tape had come from, GSK hired a British corporate investigator Peter Humphrey and his American wife Yu Yingzeng, both with long experience in China.

They started by investigating the government relations manager Vivien Shi who had left the previous December, and in the course of that investigation they "trod on a very big toe", in the words of one business source close to the story.

It turned out Vivien Shi was well connected in both the health and security apparatus.

By July the house came down on the investigators and on GSK.

The Chinese authorities have stepped up efforts to investigate corruption claims

The police publicly accused GSK of bribery. Staff were arrested and offices raided. The husband and wife investigators were taken into detention in Shanghai.

GSK said it appeared certain senior members of staff had broken Chinese law and apologised to the Chinese authorities.

But when Mr Reilly himself returned from the UK to China to help with the investigation, it soon became clear that he was not free to go, and in May of this year, police announced that they intended to charge Mr Reilly with personally authorising the alleged bribery network.

And this is where we are today, with the case in the hands of China's procuratorate and an uncertain process ahead for Mr Reilly, many of his former colleagues and for GSK.

So is this a cautionary tale or a one-off? It's both.

"Sometimes weird stuff happens," shrugged one observer, echoing a common view that the GSK case is unprecedented in China and so no one could have predicted this particular set of circumstances and events.

But it would be wise also to treat it as a cautionary tale. The same insider warned: "The game is changing and foreigners are collateral damage."

- Published30 June 2014

- Published6 August 2013

- Published24 July 2013