Hong Kong protests: What changed at Mong Kok?

- Published

Police beat back protesters who tried to surround government headquarters in Admiralty on 1 December

Clashes have erupted again in Hong Kong after the authorities moved in to clear protest camps. For two months pro-democracy activists have occupied various parts of the territory, and protests have occasionally turned violent.

Why are the authorities cracking down now?

Since the street occupations began in September in three key spots - Mong Kok, Admiralty and Causeway Bay - the authorities have largely tolerated protesters.

But the High Court began granting injunctions to businesses and industry groups to clear roads in November, triggering a round of clearances by bailiffs and the police.

The first clearance in Admiralty on 18 November passed off peacefully.

But clashes erupted the following week when the authorities demolished the entire Mong Kok camp.

Student protesters accused the police of violence, and tried to shut down government offices in Admiralty on 1 December, prompting a strong response from the police.

Another injunction has been granted to clear a section of Connaught and Harcourt Roads - the major stronghold of protesters.

Does this mean protests are dying out?

The students have insisted that public opinion is still on their side, but the numbers at protest sites and polls indicate that the public has grown increasingly weary of the disruption and unrest.

At its peak, the pro-democracy movement saw tens of thousands of Hong Kong residents from all walks of life take to the streets. Two months on, just a few hundred remain camped out in tent cities, most of whom are students and young workers.

Meanwhile, a mid-November poll done by the University of Hong Kong's public opinion programme found that a majority of respondents did not support the protests.

A majority also backed the Hong Kong government's clearance of the sites, though some believed that it could allocate other areas for protesters.

Student leaders have also found it difficult to make headway. Earlier talks with city officials proved fruitless, an attempt to travel to Beijing was blocked by Hong Kong authorities, and two leaders - Joshua Wong and Lester Shum - were arrested for obstructing police in Mong Kok and are now out on bail.

On 2 December, three of the co-founders of the Occupy Central movement called for protesters to retreat. The three turned themselves in to a police station the next day, though the authorities have not charged them with any offence.

What is the Chinese government saying?

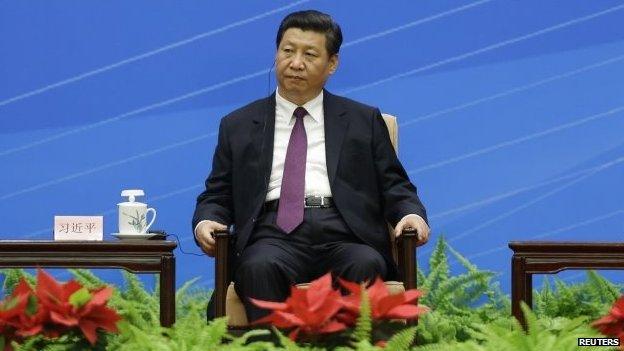

Xi Jinping has kept a firm grip on power since becoming president in 2013

China's central government has continuously condemned the ongoing street occupations, and state-controlled mainland media outlets have accused pro-democracy activists of "intensifying" the crisis with the latest clash.

One of the Hong Kong business groups that has taken out an injunction to clear the protest sites is a joint-venture controlled by Chinese state-owned Citic Group.

Though it remains unclear whether Beijing had a direct hand in the applications, many in the business sector - which is increasingly reliant on China - have opposed the protests since day one, on the grounds that it would hurt the economy and anger Beijing.