In pictures: How Hong Kong got here

- Published

Hong Kong has been rocked by one of its largest ever outbreaks of civil unrest, as tens of thousands of protesters have flooded the streets demanding the right to fully free leadership elections.

The unrest is a consequence of Hong Kong's unique historical position - a territory on Communist China's soil, but a global and connected city where many believe direct democracy is the only fair system of government.

The BBC looks at some of the turning points between handover and now.

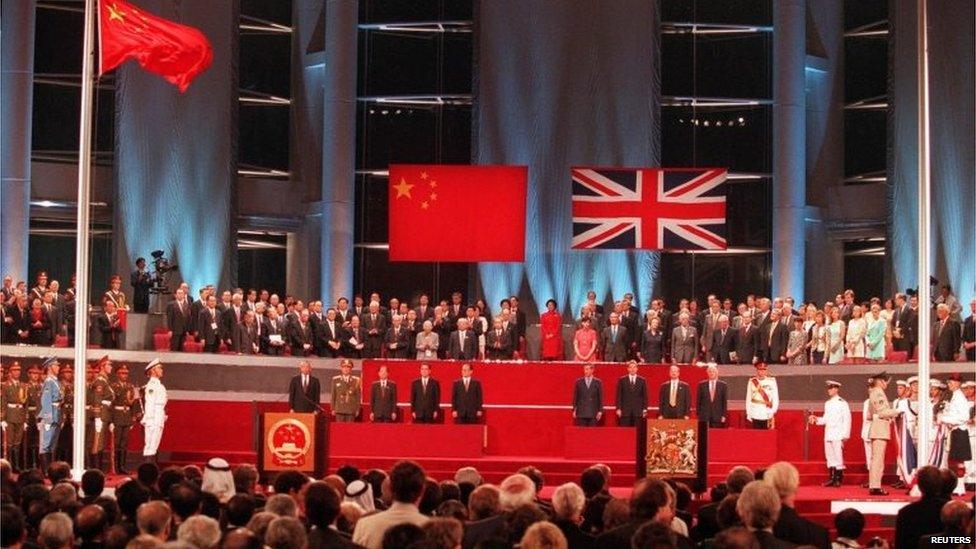

1 July 1997 - Handover

On this date the Union Flag was lowered in Hong Kong, marking the end of 150 years of British colonial rule.

Negotiations between Britain and China left Hong Kong the Basic Law, external, a de facto constitution that ensured the territory would be run under the principle of "one country two systems" until 2047. It would retain its capitalist system and preserve rights and freedoms mainland Chinese citizens did not have.

The first chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa, was elected by a 400-member Chinese committee, but the Basic Law promised that democracy would gradually develop. The ultimate aim was "the selection of the Chief Executive by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures" - but no deadlines were set.

From then on, protests have been held every 1 July, external to remind China that Hong Kong was still waiting for universal suffrage.

July 2003 - Security law protests

Proposed changes to Hong Kong's security laws brought an estimated half-a-million people out in protest.

The bill - which the government was constitutionally obliged to draw up - proposed heavy penalties for sedition and would have made it illegal for political organisations to establish ties with foreign political groups and vice versa.

It enraged democracy campaigners who said the bill was a step back for political, religious and media freedom and could be used by China to silence its critics. Ultimately, the bill was dropped indefinitely.

The following year, China ruled that its approval had to be sought for any changes to Hong Kong's election laws, giving Beijing the right to veto any moves towards more democracy.

29 December 2007 - direct elections granted

When Donald Tsang began his second term as chief executive in July 2007, he promised to publish a green paper "so that we can all work together to identify the most acceptable mode of universal suffrage to best serve the interests of Hong Kong".

Right on time, on 29 December, China ruled that Hong Kong would be able to elect its leader by the 2017 elections. Mr Tsang said this marked "a timetable for obtaining universal suffrage".

But critics - including veteran pro-democracy lawmaker Leung Kwok-hung, above - said this was too slow and not far enough.

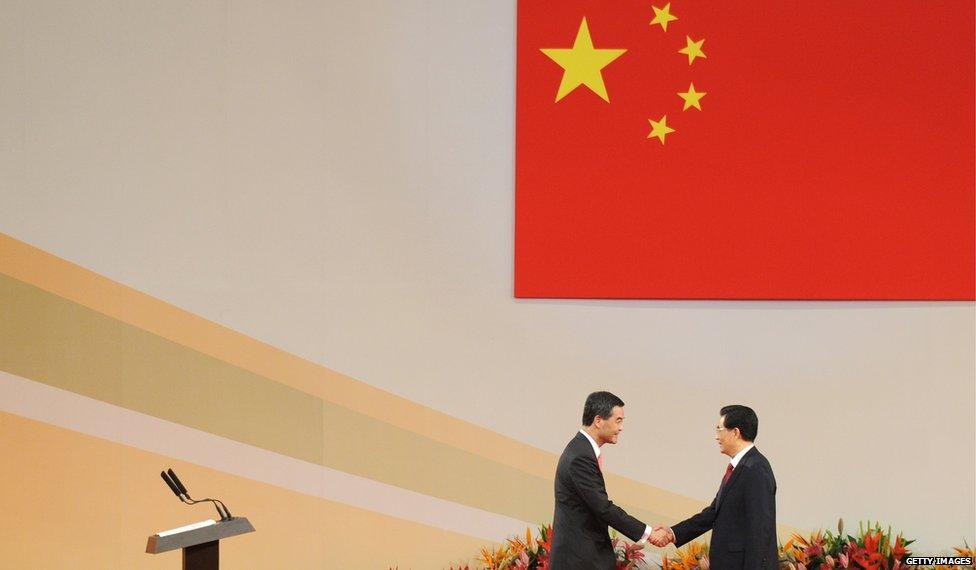

March 2012 - CY Leung-era

In March 2012, Leung Chun-ying (widely known as CY Leung) won the race to become Hong Kong's third chief executive - he was elected by a panel of 1,200 influential citizens, most of them Beijing loyalists. He was to be the last executive to gain office without public election.

CY Leung - seen here with Chinese President Hu Jintao at his inauguration in July - proved an unpopular choice among the Hong Kong public from the outset, finding it hard to shake suspicions that his loyalties lay too closely with Beijing.

Though he passed popular measures, including a tax on foreigners buying property and a ban on pregnant woman travelling from the mainland to give birth, he lost favour by proposing Chinese patriotism classes for schoolchildren.

In the face of further huge protests, the government backed down.

June 2014 - Hong Kong 'votes'

In January 2013, law professor Benny Tai published an article in the Hong Kong Economic Journal, in which he said civil disobedience was now the best way to demand democracy. The Occupy Central movement was born.

In June 2014, the group organised an unofficial referendum on how candidates should be shortlisted for the 2017 election. About 42% of voters backed a proposal allowing the public to have a greater say, alongside a nominating committee, and political parties.

China said the referendum was illegal and invalid, but Mr Tai insisted that even if it were not legally binding, the 792,808 votes cast could not be ignored.

But groups claiming to represent Hong Kong's "silent majority" who did not want to see confrontations also spoke out, saying they gathered more signatures for their cause.

31 August 2014 - China says no

Beijing had been considering for some time what form the 2017 elections would take - would Hong Kong, as many hoped, have a totally free choice of candidate?

China's top legislative committee issued its verdict in August - yes, Hong Kong would be able to elect its chief executive in 2017, but with one important caveat: a nominating committee would choose two to three candidates, who must each be approved by 50% of the committee members.

China said the "sovereignty, security and development interests of the country are at stake," and therefore "there is a need to proceed in a prudent and steady manner".

This was a bitter blow to the democracy campaigners. Occupy began planning mass protests for 1 October, China's National Day.

22 September 2014 - Students get involved

On 22 September, thousands of students walked out of the classes, mobilised by the Hong Kong Federation of Students and Scholarism. What began as a peaceful boycott and sit-in to demand democracy escalated through the week as the students converged on government HQ. When a small group , external, a number of people, including student activist leader Joshua Wong, were arrested.

Then on the evening of Sunday 29 September, Occupy Central announced that they were joining forces with the students and their occupation of the business district was beginning early.

Hours later, riot police moved in, firing tear gas at unarmed students and mounted baton charges. Not only did they fail to end the protests, the operation was widely condemned as an overreaction, prompting thousands more to join.