Hong Kong protests: Echoes of Tiananmen

- Published

Two pro-democracy protests, 25 years apart: Will they end the same way?

The Hong Kong protests are being seen as China's biggest political challenge since the Tiananmen democracy movement of 1989. Tim Luard, who reported for the BBC on the seven weeks of Beijing demonstrations and on the military assault that ended them, says although there are many parallels between the two protests, they will not necessarily be resolved the same way.

The haunting similarities between the Beijing Spring of 25 years ago and the Hong Kong Autumn of today are hard to avoid.

In both cases, many tens of thousands of demonstrators have occupied the central streets and squares of a major city in a direct challenge to the normally sacrosanct authority of China's Communist Party.

Both movements have started among students - traditionally viewed in China with special reverence - but have grown into broad-based campaigns of civil disobedience that have been largely self-driven.

Besides having the same spirit of youthful idealism, the two sets of demonstrators have shared a similar mood of elation tempered by a mixture of calmness, politeness and stoicism.

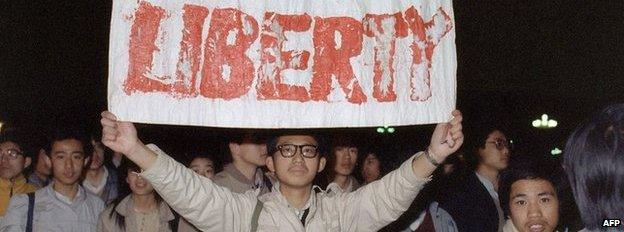

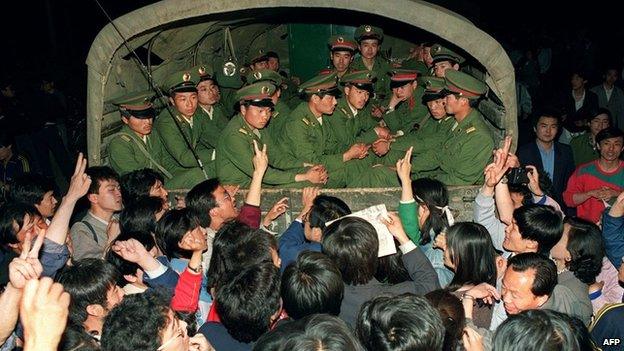

In 1989, tens of thousands of students joined protests in the Chinese capital

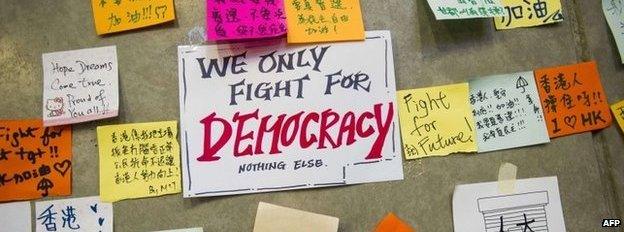

In Hong Kong, crowds have swelled each evening for pro-democracy rallies

As was the case in Beijing, the Hong Kong protesters have found most passers-by to be friendly and supportive. Non-demonstrators have given them food and water. Others have decided to join in themselves.

Reporters in Beijing in 1989 were amazed to see normally dour-faced party functionaries suddenly transformed into singing and smiling insurgents, openly calling after a lifetime of blind obedience for their communist leaders to step down.

The support of many of Hong Kong's business community for the students - even if they admit they are "trying for the impossible" - is barely less astonishing, in a place famed for its money-minded pragmatism. There is the same sense of infectious excitement at having broken out of a mould, if not for ever then at least for a few more days.

A policy of non-violence and the absence of any weapons beyond primitive gas masks and the occasional makeshift barricade have been common to both movements. When faced with lines of riot police the tactic now, as then, has been to talk and reason, giving ground if necessary before surging back.

Even the official words used by China to condemn the protests sound familiar: they are harming "social stability" and have been instigated by "hostile foreign forces".

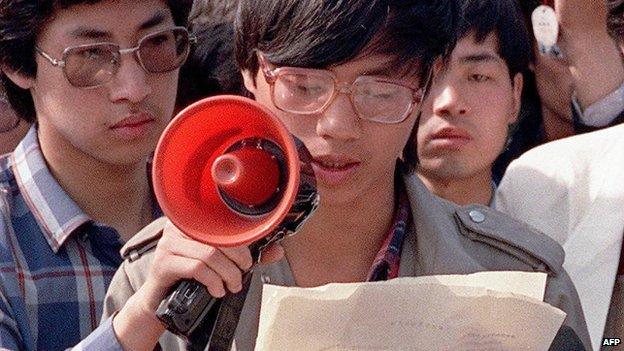

Wang Dan was one of the most high-profile leaders of the Tiananmen Square student protests

In Hong Kong, Joshua Wong is leading one of the student groups driving the protests

New power, new confidence?

So, when things become altogether too embarrassing for the Communist leadership or its patience simply runs out, will it finally respond to the current protests in the same way as before?

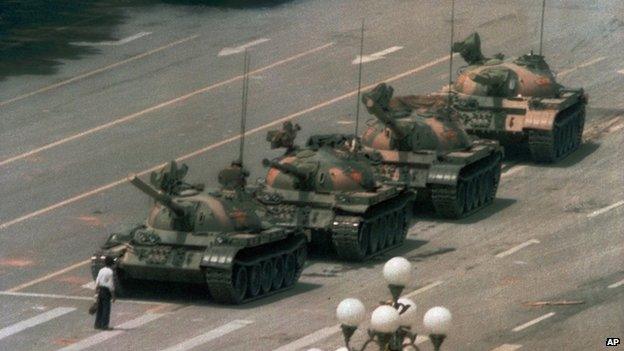

Hundreds if not thousands died as tanks and troops firing live ammunition advanced on Tiananmen Square.

It seems inconceivable that China would again resort to armed force - turning "Umbrella Man" into "Tank Man" - in front of the world's media.

Yet few of us believed at the time that the army would ever open fire on unarmed students in China's capital, where there were also plenty of foreign journalists on hand.

"Tank man" - a lone figure defying authorities - became the defining image of the protests

In Hong Kong, it is the humble umbrella that has become the protest symbol

The Chinese government rode out the ensuing storm of international condemnation, and has since managed to erase almost all knowledge of the event among its own people - if not among the people of Hong Kong, where there's an annual commemoration.

China's wealth and links with the outside world have grown immeasurably in the past quarter century, so it now has far more at stake.

But with new power has come greater confidence to do as it pleases.

The country's current leader, Xi Jinping, has shown himself to be a staunch upholder of national sovereignty and a tough opponent of political liberalisation and public protests.

Some believe there may be another side to him, seeing as a small sign of hope a rumour that his father was one of the few senior party figures at the time of Tiananmen to counsel against the use of force.

The only apparent alternative to a crackdown at present is to make concessions. Yet even to agree to negotiations would be viewed as a sign of weakness - and to concede to Hong Kong's demand for truly free elections would be unthinkable.

One key difference: Would authorities crack down now as they did then?

In Hong Kong, relations between protesters and police have remained cordial, since riot police withdrew

Mr Xi may well feel inclined to sit back and let the Hong Kong government sort out its own problems.

The use of tear gas by Hong Kong's police has already backfired, but it may be that the protests can be contained or neutralised till they simply die out. There could perhaps be an acceptable offer of a consultation process over democratic reform.

But the longer the defiance in Hong Kong continues, the more chance of contagion to other parts of China, despite the efforts of the censors.

Although it's forgotten by many, the Beijing protests of 1989 spread during their latter stages to dozens of other Chinese cities. Perhaps that's because they were allowed to go on for almost seven weeks.

There are those in Beijing today who may be saying Hong Kong must not be permitted to get away with its own rebellion for that long.