Has President Xi Jinping achieved his China Dream?

- Published

Did China's Xi Jinping achieve his aspirations for the country in 2014?

A China year is never short of changes, but one things that stays the same is the leadership's love of a political slogan.

2014 was a year with two: The China Dream and The New Normal.

The China Dream was not strictly a 2014 slogan but this year saw it put on weight.

It's counter-intuitive to suggest that a dream should feature a succession of handcuffed middle-aged men weeping piteously in a courtroom, but the dream narrative could not possibly take hold amidst the greed, cynicism and depravity of the Party machine which Xi Jinping inherited from his predecessors.

So his China Dream had to be launched on a tide of tearful corruption confessions.

The fall of the once-mighty has been a yearlong spectacle only slightly less savage than the tumbrels and guillotines of the French Revolution and precisely designed to avoid China's Communist leadership going the same way as the French aristocracy.

This month, China formally announced the arrest and expulsion of former security chief Zhou Yongkang

The key takedown was the former security chief Zhou Yongkang.

China watchers spent much of the year arguing about whether President Xi had the political clout to grapple this "tiger" into court, and whether his objective was cleaning up the system or just clearing out political rivals.

But by year-end, there were criminal charges against Zhou and a stream of sensational anti-corruption investigations in the top ranks of the People's Liberation Army, the state-owned enterprises, police, judiciary and media.

President Xi's China Dream was about resuming a place at the forefront of the world and through purges, austerity and "rectification", he spent the political year trying to build the resilient authoritarianism to get China there.

In September, prominent Uighur academic Ilham Tohti was jailed for life on separatism charges

Dreaming different?

But this is still one man and one dream, both of them carefully wrapped in the national flag.

Those of his fellow citizens who dared to dream a different dream in 2014 had a terrible year.

Political liberals, Christian pastors, Uighur academics, internet activists, even those inside the establishment who the state deemed too ready to share their opinions with foreigners - they all found themselves behind bars.

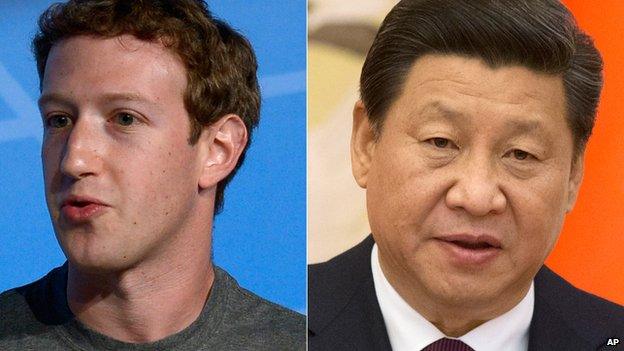

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg was spotted with a copy of President Xi's book on his recent visit to China

It's no accident either that this was the year President Xi published a book on governance.

His message was that due to its special history, culture and circumstances, China has always and will always follow a different path.

In November, he told US President Barack Obama that "the gene of traditional Chinese culture is deeply planted in the mentality of modern Chinese". The Central Party School began teaching Confucius as well as Marxism Leninism.

China has underlined the importance of "patriotic education" in schools and universities

There were some ironies in all of this.

For example, in 2014 China celebrated its first Constitution Day, but its biggest search engine Baidu banned internet forums about the constitution.

Similarly, the Communist Party Plenum in October focused on the theme of rule of law without mentioning that some of the country's most prominent lawyers are now behind bars.

China, the world's biggest internet censor, held its first world internet conference.

A cardboard cut-out of President Xi stands in a protest site in Hong Kong's Admiralty district

'When dictatorship becomes a fact, revolution becomes a duty'

But ironies are less glaring where there's only one point of view, and the central project of the China Dream is shaping the minds of its young citizens before they're exposed to alternative viewpoints.

On this score, the key lessons of 2014 were delivered not on the Chinese mainland but in Hong Kong.

"When dictatorship becomes a fact, revolution becomes a duty", read the T-shirts of some of the young Occupy Central protestors, in a jarring challenge to the China Dream slogan.

It must have been unsettling for Beijing to observe that the younger and better-educated the citizens of Hong Kong, the more pessimistic they seemed about their future under Chinese rule.

But as week followed week in the Occupy encampment, the Chinese government played its cards adroitly, making no concessions on the key electoral demands and letting local government take the heat.

Crucially there was no major flare up of sympathy protest on the mainland, underlining the importance of the "patriotic education" campaign in schools and universities, an education which reminds young mainlanders of the humiliations of their history and the benefits of unity and political stability under the firm leadership of the Communist Party.

Joshua Wong: The teenage face behind Hong Kong's democracy movement

Like Hong Kong, Taiwan also saw its own dramatic student protests: the Sunflower Movement

To drive home that message, 2014 saw the introduction of two new national remembrance days, one to commemorate the defeat of Japan and the other the Nanjing massacre.

And it was no surprise that Beijing used all the propaganda tools at its disposal to convince the wider mainland public that foreign hostile forces were behind Occupy Central.

But Beijing has no direct access to young minds in Hong Kong and 2014 demonstrated how limited Chinese soft power is without it.

A lesson taught not just in Hong Kong, but also in Taiwan, which saw its own dramatic student protest in the late spring.

Like Occupy Central, Taiwan's Sunflower Movement was also driven by distrust of Beijing and distrust of local politicians seen as advancing Chinese objectives against the interests of their own citizens.

It was surely one of 2014's big China paradoxes that China was determined to paint these movements as the work of hostile powers, whereas in fact the opposite was true. Both the Occupy and Sunflower protests flourished despite an almost complete absence of international encouragement.

Should Beijing be more worried that this generation of Chinese citizens had the political grit to do it for themselves? Or more satisfied that its swelling economic might allowed it to quell the unease of democratic governments? It's hard to judge.

For the first time in more than 140 years, the US lost the title of the world's largest economy - to China

'The new normal'

But that brings me to economics and China's other big slogan of the year: the new normal.

2014 was the year the International Monetary Fund declared that China's economy had overtaken the United States on one key measure of scale, purchasing power parity.

Beijing pushed ahead energetically with plans for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific and the Silk Road Economic Belt, all fertile territory for the China Dream, projects designed to signal to the rest of the region where its future interests lie.

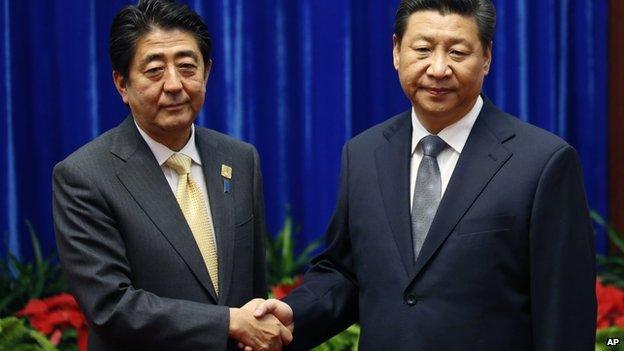

And the Apec forum in Beijing in November provided the perfect stage for Xi Jinping to deliver that message, and to tone down a rivalry with Japan which was hurting business and diplomacy.

But behind another year of mesmerisingly huge China numbers - from infrastructure investment to naval build-up and internet growth - is the most important economic story and the one that will decide the future of the China dream: economic reform.

Blues skies, world leaders and this handshake - the summit held in Beijing in November saw many highlights

The new normal is Beijing's signal that however painful, it intends to put economic reform before high speed growth. For three decades China has grown at an average of nearly 10% a year but pressure on the environment and the social fabric means that is no longer possible.

President Xi has said 7% "is not scary" and Prime Minister Li Keqiang now says "reform will be the stimulus".

Even if it underperforms on its 7.5% target for 2014, China's economy will still have seen a growth rate much higher than any developed country.

But many of the structural economic reforms pledged at the end of 2013 had not taken place by the end of 2014, while growth was still relying on debt-funded investment, casting a darkening cloud over property and land prices.

Without high land sales, local government revenues are in trouble, and the house of cards that is local government debt may jeopardise financial stability.

Despite dire warnings that there will be no bailouts, Beijing has not made an example of any major state enterprise or local government, presumably for fear of both the immediate protest which might follow and the damage to confidence in the entire financial edifice.

Can China's crackdown on corruption accelerate further economy reform in the country?

Which brings us back to the tearstained courtroom where we started: anti-corruption as the first act of the economic reform drama, removing the robber barons at the top of the state sector and then breaking up their monopolies so that a more innovative and entrepreneurial private sector can step into the gap to drive a new growth in consumer and service industries.

In this brave new normal, local governments would have a secure fiscal base no longer dependent on land sales, and infrastructure and property investment would no longer be the addictions they are today.

But building this new normal is a race against time.

In 2014, Beijing managed to deftly paper over the contradictions of the old but the longer this economic rebirth takes, the more painful it promises to be.

In short, the China Dream can't get much further until the new normal is born.

Next week, Carrie will look at China's prospects in 2015.

- Published9 November 2014

- Published16 December 2014

- Published14 November 2014