Cracking China's corruption: Huge hauls and long falls

- Published

Nanjing Party Secretary Yang Weize came under official investigation for corruption in January

Only days into 2015, revelations continue to emerge from China on the anti-corruption front.

So far this year a powerful spy chief, the Nanjing party secretary and a top diplomat have been placed under investigation.

This suggests there will be no let-up in the campaign that has run relentlessly for two years under President Xi Jinping. So let's take stock of what's happened so far.

1. What drives Xi?

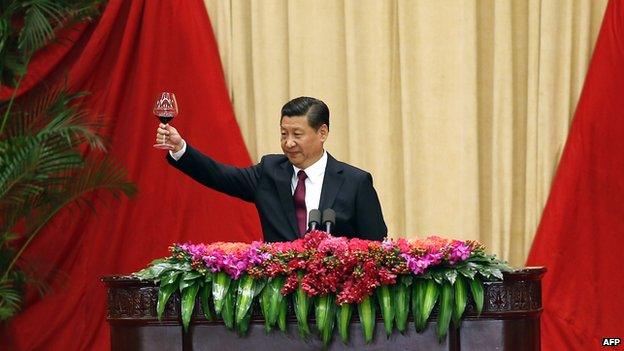

State media have hailed President Xi's approach towards stamping out corruption

On 20 November 2012, soon after becoming Communist Party leader, Mr Xi made a speech.

"Lots of facts tell us that corruption is becoming more and more rampant, and eventually, the party and the country will fall. We have to be vigilant", he warned.

Since then, Mr Xi - who hails from a revolutionary family and is tasked with keeping the party in power - appears to have propelled his anti-corruption campaign forwards with zeal.

And he famously promised to "catch both tigers and flies", making it clear that top ranking officials would not be spared.

2. Tigers and flies

.jpg)

Former Chinese security tsar Zhou Yongkang became the highest ranking official to fall

Then he followed up: By far the biggest tiger caught so far is Zhou Yongkang, the former security chief. He has been stripped of party membership and handed over to the judiciary.

Ma Jian is also a big tiger: he was in charge of China's intelligence operations.

Another tiger is Ling Jihua, once a top aide to former president Hu Jintao and a hopeful for even higher office.

General Xu Caihou is a big army tiger - he used to be a politburo member and vice-chairman of the military commission.

According to the party's discipline watchdog, in 2014 alone some 23,464 people were disciplined for violating the party's anti-corruption regulations, from all levels of the party and state apparatus.

3. Most dramatic falls

Thousands of officials in China have been investigated on suspicion of graft and corruption

Wang Min, party secretary of Jinan City, made a televised speech about combating corruption on 18 December 2014; later that day he was taken away for investigation.

A similar fate hit Wan Qingliang, party secretary of Guangzhou. When the probe into him was announced in June 2014, many civil servants under him were at meetings studying a speech he had made the previous day.

Text messages about Wan's fate were passed around and the meetings had to come to a halt.

4. Cash and more cash

Many of the fallen officials have been accused of taking bribes - and many apparently prefer cash.

When Wei Pengyuan, a senior Energy Ministry official, was taken away in May 2014, investigators found cash in his house totalling more than 200m yuan (roughly £20m).

This, state media said, became the biggest cash haul in a corruption case since the communists took power in 1949.

Sixteen machines were used to count the cash, and four broke down due to the extensive heat.

5. Gold and foreign money is fine too

Ma Junfei reportedly accepted bribes in several currencies

Ma Junfei was appointed deputy director of Hohhot Railway Bureau in Inner Mongolia in 2009.

According to media reports, on average he took bribes every other day while on this job, accepting US dollars, Euro, British pounds and gold as well as the Chinese currency, his take totalling 130m yuan (£13m).

In order to hide these bribes, he had to purchase two houses in Beijing and Hohhot.

6. Money for water

Ma Chaoqun used to be in charge of Beidaihe City water supplies, in Hebei province.

Nicknamed "water tiger", state media said he demanded money openly from any business opening in Beidaihe that needed to have water connected, including hotels, factories and party and government offices.

If the money was not enough, supplies would be cut off immediately.

After his downfall, cash totalling 120m yuan, 37kg of gold and 68 housing certificates were found in his possession.

7. Maotai still tastes nice

Often called China's national liquor, Maotai is often served to distinguished guests

Feng Yuexin, who worked as police chief in various departments in Qingdao, was given the death sentence in 2014 for protecting criminal gangs.

When his residence was searched, investigators found 1,853 bottles of Maotai, the national drink of China, among other things.

Feng reportedly loved the spirit, and would go to extraordinary lengths to obtain a good bottle, sometimes at 80,000 yuan a bottle (£8,000 ).

One estimate put the value of his Maotai collection at 2m yuan.

Feng was found to have embezzled public funds.

8. How many is enough?

"Forbidden City": This January 2014 file photo shows Gu Junshan's mansion in Henan province

In December 2013, Wu Zhizhong, a senior official in Inner Mongolia, was given a life sentence for corruption.

Wu had 33 houses inside China and one house in Canada, far beyond what his salary could afford. The keys to these houses filled a handbag, according to Chinese media reports.

9. The reporter who dared investigate

On 31 March 2014, Xinhua reported that Gu Junshan, a top PLA official, had been turned over to the military court on corruption charges. This came as no surprise, as it confirmed earlier reports by a financial journal.

Journalist Wang Heyan first broke the news that Gu was in trouble. As chief investigative reporter for Caixin magazine, she pushed hard between 2012 and 2014 to examine Gu's business empire and personal wealth. Her findings caused a stir across the country.

In Gu's house, case after case of Maotai was found, plus a model ship, a basin and a Mao Zedong statue all made of gold.

His mansion is nicknamed "Forbidden City", after the ancient imperial palace, because of its grand style.

10. The jailed activists

Activists hold banners demanding the release of prominent Chinese activist Xu Zhiyong

Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign has so far won popular support, but ordinary citizens seeking greater transparency have not always been welcomed by the authorities.

The New Citizens Movement made public calls for government officials to disclose their assets.

This did not happen. Instead, group founder Xu Zhiyong was jailed for four years in January 2014 on public disorder charges. Several other members have since been given jail terms.

Foreign newspapers examining Chinese leaders' fortunes, including Xi Jinping's, have also been penalised by the authorities, from having their websites blocked to being refused visas for journalists.

It seems that the anti-corruption battle is complex, and those not singing from the same hymn sheet as Mr Xi are heavily frowned upon.