Modi braves the 'Chinese whirlwind’

- Published

China's troops recently took part in a Moscow parade

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi arrives in China at a moment when his hosts' ambitious plan to redraw the map of Asia is gathering momentum.

China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi calls it a "Chinese whirlwind, external" in the world, and President Xi Jinping talks of an "Asia-Pacific dream" to set alongside the "Chinese dream of rejuvenation".

Beijing's shorthand for this regional effort is "comprehensive connectivity".

It means using investment, commerce, diplomacy and finance to create a Sinocentric network of Asian infrastructure and institutions, with each policy lever enhancing the next to bind the region firmly into a Chinese embrace.

A waking China "is a peaceful, amiable and civilised lion", says President Xi. But who goes into the lion's enclosure without armour?

The challenge for the Indian prime minister is the same as for many other Chinese neighbours: to establish common interest with the amiable lion while hedging against the possibility that its temper turns nasty.

Increasingly confident that its ascendancy is irreversible, China's new leadership under President Xi has turned its back on the foreign policy maxim that dominated Chinese thinking for three decades - "to bide our time and conceal our capabilities".

The war chest for the "whirlwind" is China's $4 trillion (£2.5tn) in foreign exchange reserves.

The new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, external along with other Chinese-led financial institutions will spend billions on building high-speed rail, energy pipelines, roads, ports and industrial parks. India would like to tap into Chinese money and infrastructure expertise.

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

Twenty-one Asian countries signed a memorandum of understanding on 24 October 2014 to establish the bank

Led by China, headquarters will be in Beijing

Will help finance construction of roads, ports, railways and other infrastructure projects in Asia

Expected to be fully established by end of 2015

As of 15 April 2015, there are 57 prospective founding members, 37 from within Asia and 20 from outside the region

Those from outside the region are: Austria, Brazil, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UK

Honeymoon over

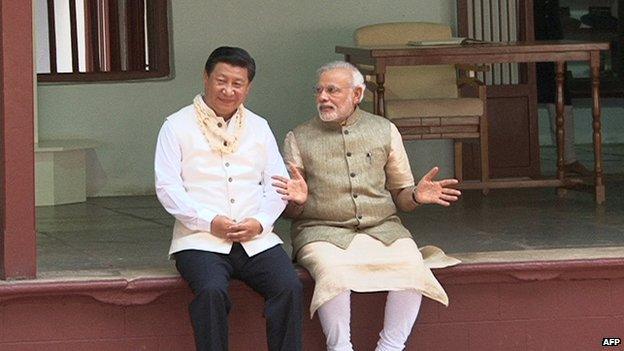

When President Xi went to India last September, Mr Modi was only four months into office, and their summit could be presented as a honeymoon of new beginnings.

They announced a slew of business initiatives, including Chinese investment of $20bn. Eight months on, progress has been slow.

Mr Xi visited India last year

Chinese investors complain of Indian red tape, Indian exporters complain of Chinese import barriers.

India's growth now promises to outpace a slowing China, but its economy is a fraction of the size and is just one of many competing for Chinese investment.

Despite Mr Modi's electoral message of faster economic development, and his "Make in India" campaign to attract investors, Chinese businesses detect little change on the ground.

And all the time, China's "whirlwind" gathers pace.

To the north of India, China's so-called "Silk Road Economic Belt, external" is intended to roll out a network of Chinese infrastructure, commerce and strategic assets through Central Asia. And to the south, its "Maritime Silk Road" is intended to do the same across the Indian Ocean.

China has swiftly become an enormous investor in Sri Lanka, the Maldives and the Seychelles.

Similarly Nepal and Bhutan, both traditionally part of India's sphere of influence.

Last month, China's president visited Pakistan, pledging $46bn investment in road, rail and energy projects and an "all-weather strategic partnership of cooperation".

No wonder Indian security analysts complain of strategic encirclement.

India vs China - in 60 seconds

Who's encircling who?

But India is playing the strategic great game too.

Mr Modi made a trip to Japan long before this week's visit to China.

One state-owned Chinese newspaper commented acidly: "The Japanese side may be excited about Modi because it wants to work together to contain China.

"But Modi's interest is Japanese investment and technology: India and Japan are like a couple sleeping on the same bed, but dreaming very different dreams."

Wang Yi has talked of a "Chinese whirlwind"

Four months later, Mr Modi invited US President Barack Obama to be chief guest at India's Republic Day celebrations.

The two made a joint statement on their "strategic vision for Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean region, external", which included lines directed at China about the importance of safeguarding maritime security, ensuring freedom of navigation "especially in the South China Sea", and urging all parties "to avoid the threat or use of force".

And here we come to the heart of the problem for Mr Modi.

China's strategic vision for the region is to weaken US influence and make full use of its economic might in doing so.

President Xi said last year: "It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, external."

For as long as the US continues to engage with China, and China accepts the legitimacy of the American presence in the Western Pacific, it may be possible for India and other regional powers to continue to play both sides, to benefit from economic ties with China and a security framework with the US.

But if the US and China drift towards more open competition, the core of that rivalry will be who has better friends, and everyone in the region will have to make hard choices.

Problems from history

Those neighbours of China who have no territorial dispute with Beijing can perhaps put these looming risks to the back of their minds, but India cannot.

Despite 18 rounds of border talks over more than a decade, Beijing and Delhi have been unable to resolve the territorial disputes that brought them to war in 1962.

Ladakh is a disputed territory in the Himalayas

Even last September, President Xi's visit to India was overshadowed by a Chinese troop incursion in the Himalayas, external.

The good news is that this row is at a low simmer rather than boiling point.

In contrast to Beijing's fierce denunciations of Japan, the Philippines or Vietnam over territorial rivalries in the East and South China Sea, its tone is relatively mild on India and a dispute it describes as being "left over from history".

For the time being at least, China seems prepared to show flexibility in a relationship that shifts fluidly between cooperation and competition.

Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang has said before (and will probably say again before the week is out) the combined population of China and India accounts for more than a third of the world's total. When we speak with one voice, the world will listen.

During this week's summit, there will be one voice on the benefits of yoga and T'ai Chi, one voice on the resilience of ancient civilisations and the resonance of a shared Buddhist heritage.

But when all the warm words and toasts are over, the question for Asia's two giants will still be if - not when - they can find a way to speak with one voice on the things that determine the future.