Humphrey shattered by time in Chinese jail

- Published

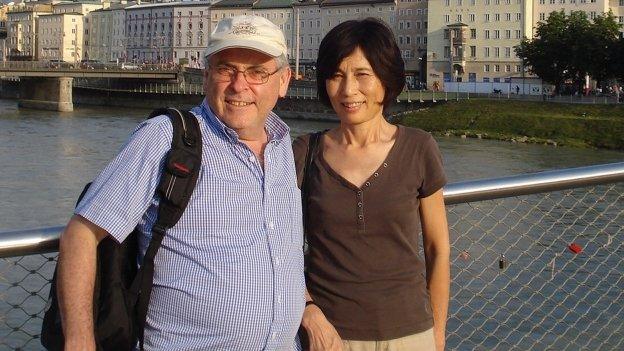

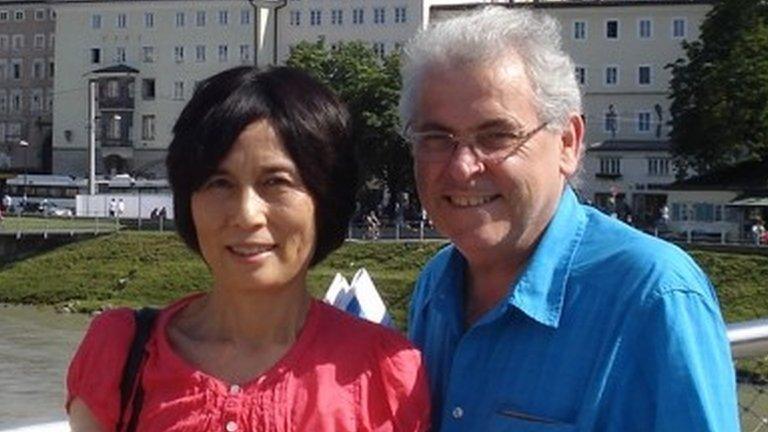

Mr Humphrey and his wife were arrested for allegedly buying and selling personal information

Free at last and back on British soil after being deported from China, Peter Humphrey told me his two years in a Shanghai jail cell had been a shattering experience.

Speaking over a welcome pint of Guinness in the bar at Heathrow airport, he was clearly angry, saying Chinese prison authorities had denied him treatment for a prostate problem which has now become a tumour.

"I was constantly harassed in prison over signing a thing they call an admission of guilt and a statement of remorse," he said.

"I never signed those documents because I did not admit to having committed that offence as charged.

"Therefore, that's why they tried to extort this confession by withholding medical attention for my prostate condition."

Peter Humphrey and his wife were detained during a Chinese police investigation into corruption at pharmaceuticals giant GlaxoSmithKline.

GSK made a public apology, external and was fined £300m, external after being found guilty of bribing Chinese doctors to buy its medicines.

Although Mr Humphrey and his wife were not implicated in the bribery case, they had been hired by GSK to investigate a sex tape sent to the company's headquarters in London, and were convicted in a separate trial of selling the personal data of Chinese citizens to corporate clients.

Mr Humphrey was released early on health grounds on 9 June. Yu Yingzeng, a Chinese-born US citizen, was freed two days later.

She had a month of her two-year sentence to serve. He had seven more months of his two-and-a-half year term remaining.

Fighting corruption

The irony of all of this is that Peter Humphrey's business was built on fighting corruption.

His company ChinaWhys was usually hired by multinationals struggling to investigate internal fraud problems.

His misfortune was to get swept up in the perfect storm which engulfed GSK's China operation in 2013.

A falling-out in the company's top management team led to the departure of a key Chinese member of staff and soon anonymous whistleblower emails were arriving at GSK headquarters in London, followed by the sex tape involving GSK's China boss in April.

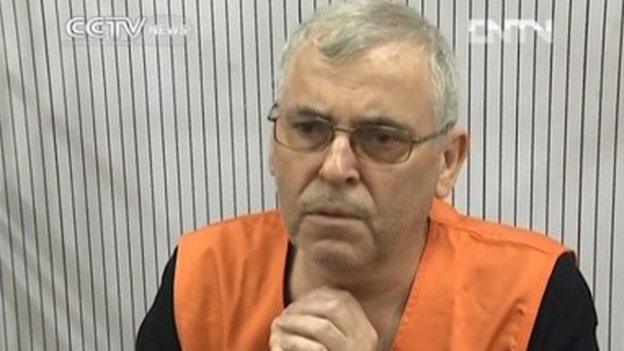

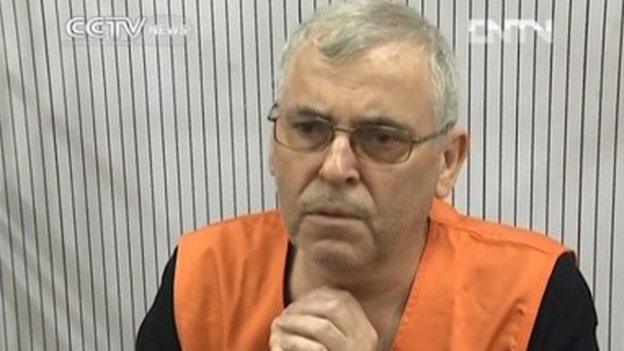

Peter Humphrey was convicted in 2014

I am very interested to hear what Peter Humphrey has to say about what happened next, the period between being hired by GSK to investigate the sex tape and his arrest in July.

But on his first day back in the UK, he told me he was not yet ready to discuss GSK.

Business risks

Meanwhile the pharmaceuticals giant is trying to learn lessons after facing one of the largest fines in Chinese corporate history and two years of turmoil in one of its fastest-growing markets.

The case highlights the risks for foreign companies of doing business in a country where politics can often trump economics and where the red lines on what is acceptable business practice often shift.

President Xi Jinping has launched a drive against corruption

It is a market where government relations are vital and where foreign companies need to map the political relationships of key employees and local partners.

In 2013, when this perfect storm was breaking around GSK, there was the added uncertainty surrounding a new leadership.

President Xi Jinping had just launched his anti-corruption campaign, and competing regulatory authorities were falling over each other to show their determination to crack down.

When GSK's internal problems spilled so sensationally into the world of politics and police, it was a moment when the red lines on acceptable business practice had suddenly shifted.

The company presented the perfect target for the wake-up call to the international business community which Beijing was keen to send anyway.

Collateral damage

For two years, Peter Humphrey and his wife were collateral damage and now he needs urgent medical treatment for a prostate problem that has become a tumour.

He was also angry about the judicial process, telling me the couple were tried on state TV in China before they were tried in court.

"We were paraded in front of Chinese television in prison uniforms in handcuffs and placed in an iron cage," he said.

Of course, China says it is determined to become a "rule of law" country. But it is not there yet.

Peter Humphrey said he was extremely happy to be back home in the week when Britain is celebrating the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta.

"A milestone in Britain's political development and that is our democracy, our freedom and our respect for human rights which is a tremendous achievement here in the UK, in marked contrast with the situation in many countries."

Mr Humphrey's reference to Magna Carta over a pint of Guinness on a sunny afternoon at Heathrow reminded me of my own reflections on visiting the dedicated exhibition in the British Library a few weeks ago.

As someone with Chinese family and friends, I felt deeply sad that 800 years ago, British citizens had demanded and won rights that Chinese citizens still don't have today.

How the case unfolded:

January 2013: Email alleging bribery sent to GSK boss, followed in March by sex tape featuring China chief Mark Reilly

April 2013: Peter Humphrey's company ChinaWhys hired to investigate

June 2013: Mr Humphrey delivers his report to GSK

July 2013: China announces investigation into GSK China, police detain four Chinese GSK employees

August 2013: Mr Humphrey and his wife arrested for allegedly buying and selling personal information

May 2014: Chinese authorities accuse Mr Reilly of overseeing bribery network

August 2014: Mr Humphrey and his wife go on trial and are convicted

June 2015: Peter Humphrey and Yu Yingzeng are freed early from prison

- Published17 June 2015

- Published8 August 2014

- Published3 July 2014