China watches Greece with dismay, patience and cunning

- Published

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang will be in France for an official visit starting Tuesday

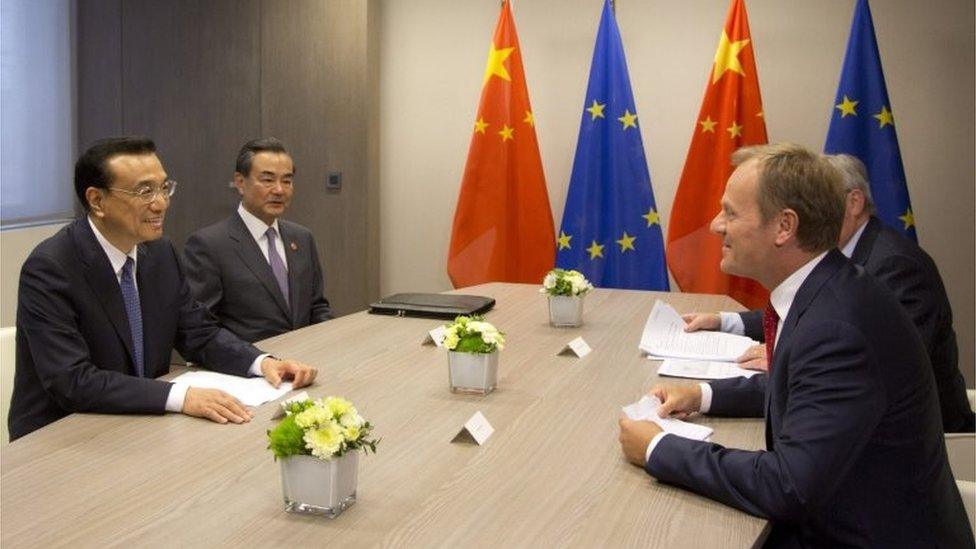

Last year he visited Athens, this year Brussels. The European Union is China's largest trading partner and Premier Li Keqiang comes twice a year.

On this occasion, he started in Brussels with the annual China-EU summit with official visits to Belgium and France tacked on.

The timing could be better.

At the European Commission, his host President Jean Claude Juncker was distracted from the impeccable choreography of a China summit by the gathering storm in Greece, as banks barred their doors, ATM queues stretched and betting shops stopped offering odds on the prospect of a Greek exit from the euro.

"China is ready to play a constructive role," said the Chinese premier when asked about Greece at a news conference in Brussels.

But Beijing is watching the unravelling of events in Athens with a mixture of dismay, strategic patience and cunning.

Dismay

China is a major investor in Greece's whole economy

Already struggling to keep growth steady at home with enormous volatility on stock markets over recent days, China has a lot to lose from the uncertainties that surround the eurozone drama.

It is a major investor in Greek infrastructure, in euro bonds and in the EU economy as a whole. Chinese deals rose from $2bn (£1.2bn) in 2010 to $18bn in 2014, according to research by Baker & McKenzie and the Rhodium Group.

Greece now spooks Beijing almost as much as it does Brussels.

First came threats to halt the privatisation of the port of Piraeus in which China already has a major stake. Earlier this year, some sections of Chinese state media thundered that Greece had "forgotten that it is the birthplace of Western civilisation which values the spirit of a contract the most".

They dusted off their Greek mythology to describe Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras as "like Phaeton, given the reins of the sun chariot only to lose control and nearly destroy the earth".

And the Global Times, owned by the Communist Party's flagship People's Daily, went so far as to complain about the unpredictability produced by the democratic electoral cycle.

"Without a robust system to guarantee political stability, administrative management in these countries is easily jeopardised by leadership changes."

Strategic patience

Greece is China great southern gateway to Europe

China's vision for Eurasia is its "one belt one road" strategy, a plan to wrap its own infrastructure and influence westward by land and by sea.

The land route is the most ambitious project to integrate continental Asia and Europe since Genghis Khan 800 years ago. And the sea route is a thread of Chinese ports and bases all the way from southern China through the Indian Ocean to the Horn of Africa and the Mediterranean.

Which is where Greece matters again. It is China's great southern gateway to Europe.

In Brussels on Monday, Li Keqiang and his host Jean Claude Juncker celebrated what they called a "connectivity platform" to combine forces on infrastructure and trumpeted China's involvement in a European investment fund for strategic projects.

On the same day in Beijing, 57 countries including all the major European powers, took part in a ceremony to launch a new Chinese led development bank.

Along with the "one belt, one road" strategy, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is intended to put China's engineering might to use building a new regional infrastructure with Chinese masterplan, technology and influence firmly at its heart.

Given its many travails, with Greece only the uppermost, the EU is in no shape to counter China's strategic march, even if it should wish to.

Cunning

China will be weighing up the costs and benefits of this crisis

"Never let a good crisis go to waste" is as resonant a maxim in China as it is in Europe.

Already some observers are suggesting a Greek exit from the euro could provide China with the opportunity to move its strategic agenda several paces up the board by buying more Greek assets at rock bottom prices.

And what about lending to Athens? As Li Keqiang smiles his way from Belgium to France today, he will be doing a careful cost-benefit analysis on the back of his café napkin.

It's a tricky equation: on one side the soft power benefits abroad for Beijing of riding to the rescue where Brussels won't, and on the other side, the bottom line cost of being saddled with a lot of unrecoverable Greek debt.

Mr Li, please send me the cafe napkin when you've worked it out.

- Published30 June 2015

- Published29 June 2015

- Published6 April 2015