Panic, invincibility and blame in China's stock market

- Published

China's latest emergency measures to calm its stock markets follow a slew of others over the course of the past week

Mainland shares have seen several days of erratic trade in recent weeks - despite moves by the Chinese securities regulator to calm markets.

The benchmark Shanghai Composite surged as much as 8% on Monday morning following a weekend of emergency meetings and more attempts to correct the volatility. It finished the trading day up 2.4%.

Here is how Chinese authorities have reacted so far:

Panic

It was all hands on deck over the weekend in a blizzard of emergency meetings and breathless headlines. Big market players were given no choice but to sign up to a government rescue.

Brokerages promised not to sell shares until the Shanghai market had recovered 4,500 points. They had to reach into their pockets on the spot for $19bn (£12.2bn) in a stabilisation fund.

All new share issues are suspended forthwith. The central bank will provide "liquidity support", in other words turn on the lending tap, to help borrowers boost the market.

These emergency measures follow a slew of others over the course of the past week.

Taken together, they constitute a stunning retreat from market principles and suggest that at this point, the government itself has little confidence in its own financial markets.

Whether any of it will work or not remains to be seen. Shanghai's benchmark index surged nearly 8% at Monday's opening with the Shenzhen exchange not far behind.

But they fell back later in the day and Beijing will not breathe out yet.

Nearly $3tn in stock values has been wiped out in three weeks and some warn that the stabilisation fund may not be enough to corral the bears and stop the slide.

Others complain that the government moves will benefit big players who buy the blue chip shares and offer little help to small retail investors.

But more fundamentally many wonder why the government is panicking at all. Investors who bought more than four months ago are still sitting on a tidy profit given that shares rose 150% over the space of a year before losing 30% in three short weeks.

At home and abroad, there are analysts who argue that the bubble needed to deflate and that a short sharp downward shock for investors is a useful corrective to speculative habits.

If the underlying fear is damage to the real economy wouldn't it be better tackled by tax cuts or public spending increases?

But that is not the deepest fear. The government's terror is being seen to be incompetent and even impotent.

This is a matter of confidence which goes well beyond the stock market.

Speculators have called Beijing's bluff. The stock market has become a classic "too big to fail" problem, which is where step two comes in:

Look invincible

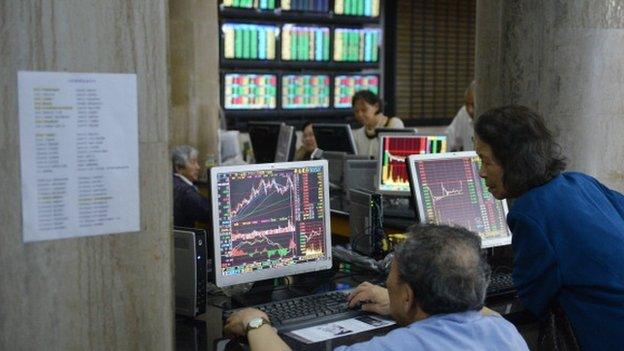

Nearly $3tn in stock values has been wiped out in three weeks

Beijing sees its own credibility as the thin red line between order and chaos.

If confidence in the stock market fails, might it also fail in the banking system, the already fragile economy and ultimately in the management of all three?

The fact is that no one knows how much debt is out there or ultimately who stands behind it when the lenders cave in. Add to uncertainty the risk of public outrage.

Anyone who invested in shares before March is still sitting on a profit, but that still leaves a lot of people who have lost their shirt.

After all, 12 million new trading accounts were opened in May alone, the majority in the hands of buyers with little education, even less trading experience and whose stock market adventure was funded by borrowing.

The first rule of governing China is to keep angry people off the streets. Hence the paradox of a government introducing panic measures in order to look all powerful.

Of course, government taking control is not what China's stock markets are supposed to be about.

Markets require regulation but at the end of the day they need to develop effective feedback, co-ordination and a mature assessment of risk.

Government infantilising investors by galloping in to ensure the index stays up is not a market outcome.

Issuing orders to market players to buy this, hold that and freeze the next thing is a retreat to command economics.

No wonder one state newspaper has declared the stock market "a battlefield".

But what constitutes victory? And who exactly is the enemy? This leads us to step three:

Find someone to blame

There are worries the latest government moves will benefit big players and offer little help to small retail investors

A few bad apples? At the end of last week the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) announced an investigation into market manipulation. After months of suspicious trading patterns, the timing of this move will provoke a hollow laugh in some quarters.

Foreigners? On social media, rumours swirled last week about overseas investors undermining the market by betting against Chinese shares via stock futures.

But the China Financial Futures Exchange has already denied these rumours. Chinese markets are largely insulated from global pressures and foreigners are marginal players however tempting a target.

A fall guy? Many investors are calling for the regulator's head. The chief of China's market regulator is Xiao Gang and his days must now be numbered.

But the real blame should lie squarely with the central government.

Its strategy, clear for the best part of a year, has been to pump up the stock market so that it could earn billions by selling shares in state owned enterprises, and at the same time make the public feel paper-rich again after the languishing property market had made them feel poor.

On this arithmetic, government and its state owned enterprises could offload debt, and Chinese citizens could be persuaded to save less and spend more thereby energising the rest of the economy.

But this was government gaming the market for opportunistic reasons rather than building a healthy stock market for the long term.

Beijing knew better than anyone that the surge was driven by borrowing, with speculative bets made not on any clearheaded assessment of company prospects or earnings but on gaming government hype.

In March, Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of the People's Bank of China said: "A buoyant market on a solid footing could be a reliable funding source."

But what about a buoyant market on a shaky footing? Economic growth in the first quarter fell to 7% year-on-year.

And there was no sign of a turnaround in the second quarter. Until 12 June, stocks galloped ahead regardless.

All along sober heads warned that Chinese stock markets were stepping onto a "treadmill to hell".

Reform guru Wu Jinglian called the market "a casino where one player can see the cards of the other players".

Hu Shuli, editor of the financial journal Caixin cautioned against "pushing a 'mad bull' stock market to solve fundamental issues".

"Follow the trend until you find yourself in a coffin," thundered one market sceptic.

But we are where we are.

At an important crossroads where Beijing has chosen to flout its own reform agenda and move against the market. Perhaps there was an alternative to panic, invincibility and blame.

A confident Chinese government could have elected to hold its nerve; honour its pledge "to make markets the decisive force" in the economy and think about what it would do in the real crisis which threatens over bad loans and property.

Is it too late? Probably.

And worse, the events of the past 10 days have undermined reform, undermined confidence and made the real crisis substantially more likely.

- Published6 July 2015

- Published3 July 2015

- Published4 July 2015