Investigator Peter Humphrey warns over GSK China ordeal

- Published

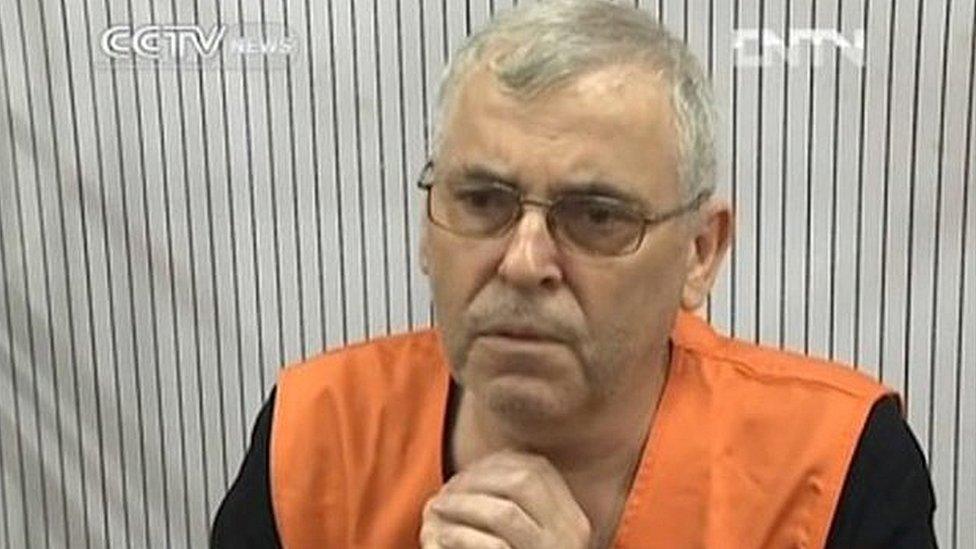

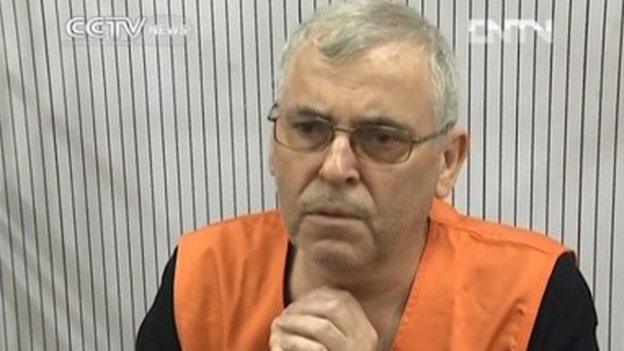

Peter Humphrey: "There are some wider lessons that come out from our case in China for the business community"

It's exactly two years since the door of Peter Humphrey's Shanghai bedroom was kicked in by police and he disappeared into a prison nightmare which ended only three weeks ago with his deportation from China.

In an exclusive interview with the BBC, the British corporate investigator who became embroiled in GlaxoSmithKline's (GSK) China corruption scandal tells me his story is "a cautionary tale which many people can learn from".

The risks of doing business in China, he says, are "on the same scale as the opportunities", and governments, including the British government, "have not been doing a very thorough job of making business understand the risks".

"Absolutely any company going to China could be the next party to suffer our fate if they fail to understand this," he says.

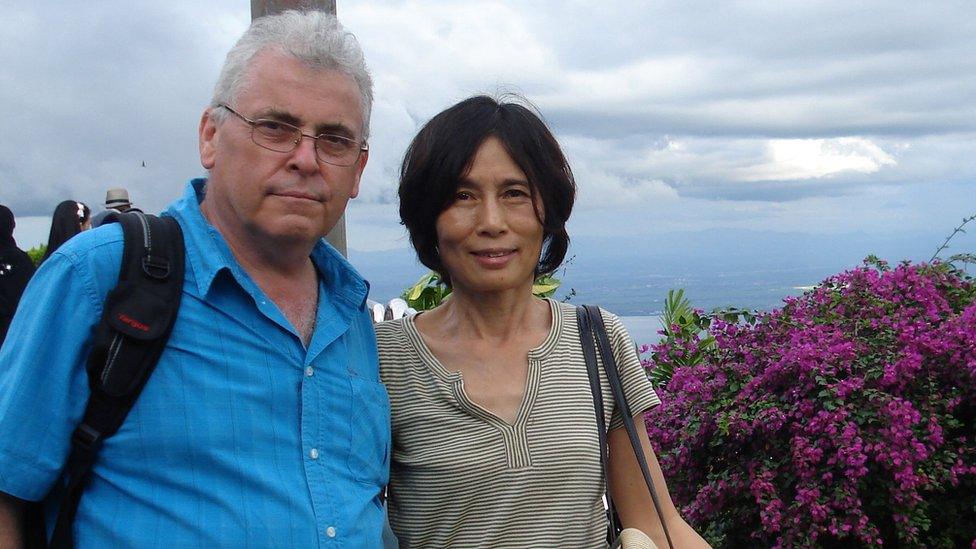

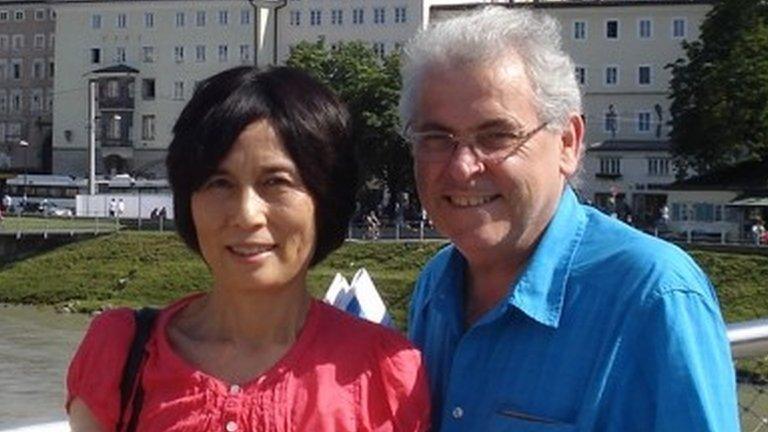

The fate suffered by Peter Humphrey and his wife Yu Yingzeng was to spend two years in squalid and crowded jail cells, to be denied urgent medical attention and to be separated from each other and from their son. The corporate investigator says it was both a shattering experience and a miscarriage of justice.

"None of our staff did anything illegal," he told me. "We engaged third parties to help us with some parts of our work. We always instructed them to follow legal means but had no control over the methods they used."

So why the prosecution and the prison term?

"It doesn't stack up at all when you analyse our case and the GSK case on the basis of the information you have. It doesn't stack up at all."

Peter Humphrey was convicted in 2014

The couple were corporate investigators who became embroiled in a Chinese police investigation of corruption at GSK. The British pharmaceuticals giant had bribed Chinese doctors and hospitals to buy its medicines.

Mr Humphrey and his wife were in no way implicated in that corruption, but had been hired by the company to investigate the source of a secretly filmed sex video of GSK's top boss in China and of whistleblower emails sent to company headquarters in London.

"I believe we were collateral damage in a wider dispute between a company and the authorities which led to us being dragged in," he said.

Even now, Peter Humphrey is reluctant to discuss the details of the GSK case or of his relationship with his former client. Asked why, he tells me: "It's not impossible that we may sue some of these parties or through other means try to seek redress."

Corruption crackdown

He says he watched the TV coverage of the GSK trial from his Shanghai prison cell. The company was found guilty of systematic bribery and fined £300m, external. He was shocked by the contrast between his punishment and theirs.

"Suspended jail sentences for three or four of the main culprits when I and my wife had been sentenced to years in prison," he says.

"Someone asked me recently why someone like Mark Reilly (GSK China's boss) could be set free and we were in jail. I think it's very simple, we don't have half a billion dollars. That story was about money from the beginning. Money got them into trouble and money got him out."

The events which led to these trials took place in the early part of 2013 when China's new President Xi Jinping had just declared nationwide campaigns against corruption and for the rule of law.

Peter Humphrey says that at the time he welcomed these developments: "We felt hopeful that a new era with a genuine crackdown against corruption, had arrived.

"What we were doing for companies in the private sector was very similar to what the government now seemed to be doing in the public sector. Unfortunately though, when such a crackdown is driven in a sort of campaign style, throughout China's history in the past 60 or 70 years, we have seen that campaigns are often taken advantage of and used to conduct personal vendettas and I think that's what happened to us. Someone took offence and then orchestrated an act of personal revenge."

Peter Humphrey and Yu Yingzeng said they had backed the crackdown on corruption

Having been deported from China, Peter Humphrey does not know whether he'll ever be able to go back. His two years in prison do not erase his 40 year affection for the country.

"I love China. I love the Chinese people I've known over the years. I've had many positive memories and experiences. This does not erase them," he says.

But once the investigator, always the investigator. From a world away in south-east England, Peter Humphrey needs to focus first on getting the medical treatment that he was denied in prison. But he is also determined to work out exactly what triggered his two year nightmare in Shanghai.

"I and my wife are not vengeful people. But we are angry because an injustice occurred. We are pursuing justice not revenge," he adds.

How the case unfolded:

January 2013: Email alleging bribery sent to GSK boss, followed in March by sex tape featuring China chief Mark Reilly

April 2013: Peter Humphrey's company ChinaWhys hired by GSK hired to investigate

June 2013: Mr Humphrey delivers his report to GSK

July 2013: China announces investigation into GSK China, police detain four Chinese GSK employees

August 2013: Mr Humphrey and his wife arrested for allegedly buying and selling personal information

May 2014: Chinese authorities accuse Mr Reilly of overseeing bribery network

August 2014: Mr Humphrey and his wife go on trial and are convicted

June 2015: Peter Humphrey and Yu Yingzeng are freed early from prison

- Published17 June 2015

- Published8 August 2014

- Published14 July 2014