The youths out to save Hong Kong's unique opera

- Published

Cantonese Opera glamour - in nine steps

It is a centuries-old art form and a unique part of Hong Kong's identity but many people fear that Cantonese opera could die out if it doesn't reinvent itself. The BBC's Helier Cheung delves into a dramatic world of make-up, martial arts and vocal acrobatics.

Mitchie Choi expected to learn martial arts and operatic singing, but not how to act like a man, when she decided to commit to Cantonese opera. The 22-year-old had just finished a linguistics degree .

"When I started learning Chinese opera, obviously I wanted to [play] a female role."

But her tutors told her she was more suited to playing male roles because of her height and deep voice.

Now, she says, she loves performing as a male character, and can't imagine doing anything differently. But the training is tough and the future rewards of this career path are unclear.

"We have to be on our feet most of the time, we're working 9-6 every day, [on] acrobatics, combat movements. We have to do the splits...and singing lessons as well," she says.

Mitchie Choi explains why she loves Cantonese Opera - and acting as a man

Cantonese Opera, a type of Xiqu (Chinese Opera) developed in southern China, is loved by many in Hong Kong - especially the elderly. Yet many fear it could become endangered as it struggles to engage younger audiences.

Although there are more than 1,000 Cantonese opera performances in Hong Kong each year, "you can argue that the majority of the audience are old or retired people", says Leung Bo Wah, a professor of Cultural and Creative Arts at the Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Attracting new performers is difficult because in a practical, almost utilitarian society such as Hong Kong's, young people think this is a hard way to earn a living.

But, Mr Leung says, it is one of the art forms that best represent local Hong Kong culture, almost part of its very identity. People "feel this is our own kind of art form" because it uses Cantonese, the language spoken in southern China.

A quick guide to Cantonese opera

Performers are trained in four skills: singing, acting, speaking and martial arts.

Initially performed in rural ceremonial rituals and folk festival celebrations.

Main character types include: the male lead, the warrior, the clown and the female lead.

Origins can be traced back more than 300 years.

Used to be performed in bamboo theatres - temporary structures built with bamboos and cloths, with few props. Now often also performed in theatres.

Ms Choi readily admits she is in a minority, she knows the art form is considered "very old and boring" by people her age.

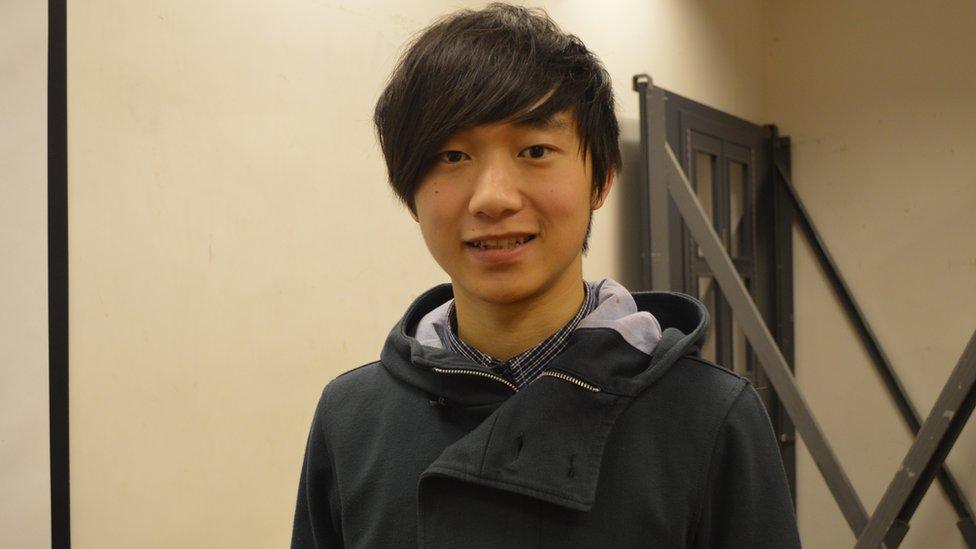

Her fellow student Ho Jun Hei, a 20-year-old training as a flautist in Cantonese opera, says that part of the problem is that many young people simply aren't exposed to Cantonese opera any more.

The pair are among very few studying for a bachelor of fine arts in Cantonese opera, a degree programme launched in 2013 at the Academy of Performing Arts as part of efforts to preserve the art form.

It has been billed by the academy as the first Cantonese opera degree in Hong Kong, and possibly the world.

Heavy headgear and elaborate costumes are all part of the performance

There are those who passionately argue for the beauty of the art form.

"Cantonese opera is really a treasure, a beautiful Chinese heritage [that is] very special in Hong Kong," says Frederic Mao, a theatre director who chairs the Chinese Opera school.

He points out that unlike other forms of Chinese opera, it has been able to develop uninterrupted for decades.

During the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution in mainland China, most forms of art and entertainment were banned, including traditional Beijing opera, and performances of Western films.

However, Cantonese opera was able to continue in Hong Kong, which was a British colony at the time, and has been "preserved and performed until today".

Cantonese opera was traditionally performed in temporary bamboo theatres

The art form got a boost in 2009, when it was recognised by the UN's arts body as an "intangible cultural heritage".

In its listing, external, Unesco said the art form had developed "a rich repertoire of stories", and also "provides a cultural bond among Cantonese speakers in [China] and abroad".

Hong Kong's government is also attempting to boost Cantonese opera in Hong Kong, building a large Xiqu theatre in a huge arts hub set to open in 2017.

The last Sunday of each November has also been designated Cantonese Opera Day, external by authorities in Guangdong, Macau and Hong Kong.

But ultimately, the future of Cantonese opera will depend less on official efforts, and more on the ability of the performers to adapt the art for younger generations.

'You need to sing, to act, to fight'

"Aside from telling people how precious it is... we have to produce the type of work that audiences will appreciate, and be interested in by themselves," Mr Mao says.

For example, the percussion in many traditional Cantonese opera performances is loud - something younger audiences find off-putting - so some theatre groups have started to adjust the sound levels.

"It's not easy to preserve Cantonese opera. On the other hand, it's exciting to bring it up to date. The art form is old, but hopefully... we can bring in some new ideas."

Flutist Ho Jun Hei enjoys the complex scripts and the musical flourishes of Cantonese opera

Frederic Mao says Cantonese opera needs to reinvent itself to stay relevant

Ms Choi and Ho Jun Hei are young and committed to rejuvenating the art. Their enthusiasm, undoubtedly, would be music to the ears of many who love Cantonese opera.