The Hong Kong fight to cash in Japanese military yen

- Published

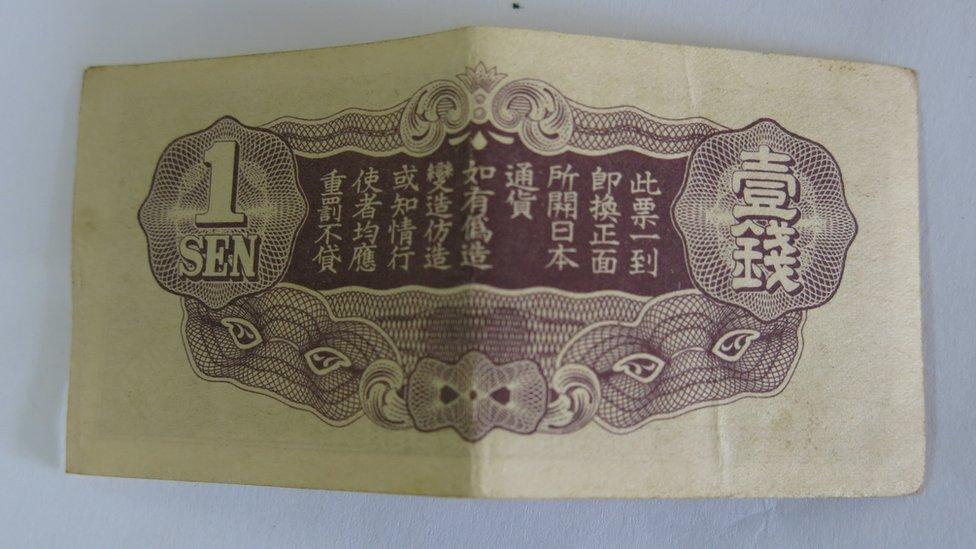

Military yen became worthless when the Japanese left

Lam Yinbun was only 14 years old when the Imperial Japanese Army defeated British forces defending colonial Hong Kong in 1941.

The occupation lasted more than three years, ending with Japan's unconditional surrender on 15 August 1945.

Ahead of the 70th anniversary of that day, Mr Lam will join a group of elderly demonstrators demanding compensation for an obscure relic of the war: cash notes called military yen that became worthless when the Japanese left.

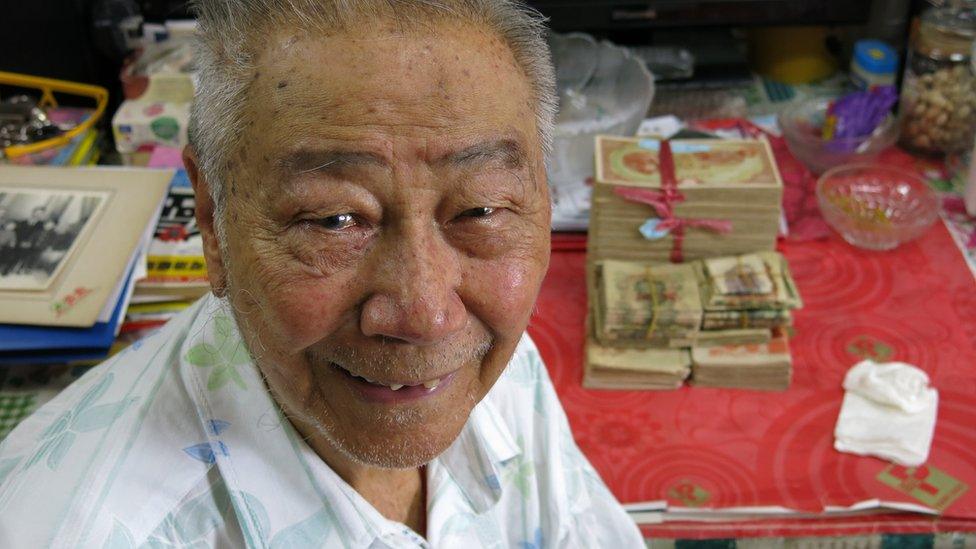

Mr Lam's stash of Japanese bank notes adds up to about 100,000 yen

"When the Japanese army took over, they immediately forced people to exchange their money for military yen," the sprightly 88-year-old says, also recalling tales of extreme brutality.

He remembers queuing behind the Peninsula Hotel to change money.

Mr Lam has 100,000 worth of military yen, in notes from 100 yen, the biggest denomination, to one sen, the smallest denomination.

He received the money from his parents, who were forced to sell their small grocery store business due to difficulties during the occupation.

After the surrender, Japan's finance ministry declared that military notes were no longer exchangeable for ordinary yen.

The policy of the British colonial government was to refuse the yen, for fear of large inflows of such cash from southern China.

"It is suggested that all occupation currency should be destroyed immediately and that a relief office by the Government be set up for the amelioration of hardship in deserving cases using only lawful currency or assistance in kind," according to a document written by colonial officials in August 1945.

Japan surrendered unconditionally in Hong Kong in 1945

But the money was not completely destroyed.

Hong Kong families have been fighting to convert the notes to legal, useable tender since the first post-war years.

The Reparation Association of Hong Kong, of which Mr Lam is a member, says some 3,500 families here own military yen with a face value of more than 540 million.

The group has kept meticulous notes. One family has more than six million worth of military yen.

It is difficult to say exactly what those notes would be worth now.

The association fought for six years in a Tokyo court asking the Japanese government to honour the notes. Their demands were rejected in 1999.

But Lau Man, president of the association, has vowed to continue fighting.

"We believe the Japanese government will have to settle this matter sooner or later," he says.

The association would consider accepting a settlement from the Japanese government along the lines of a previous offer made to former soldiers in Taiwan.

Mr Lam said he would consider spending some of the money in Japan

In 1994, the Japanese government agreed to pay the unpaid wages and frozen savings accounts of Taiwanese soldiers who had served in the Imperial Army.

Japan offered to repay the money at 120 times the wartime rate.

At that rate, the 540 million in military yen owned by Hong Kong families would be worth about 65 billion yen, or $520m (£330m).

Mr Lam's share would be around $96,400 at current exchange rates.

The retired father of eight is comfortably well-off and has no financial issues, but says he and his family deserve to be treated fairly.

He holds no grudge against the Japanese people, even suggesting he would be happy to spend part of the compensation money in Japan.