China one-child policy: U-turn may not bring prosperity

- Published

For more than three decades, the Chinese government has taken control of the most intimate details and choices in people's lives.

It has issued and withheld baby permits, policed menstrual cycles and ordered abortions.

Because the job prospects of family planning officials have often depended on reducing live births, the result has been a catalogue of horrifying human rights abuses including forced late-term abortions and sterilisations.

Combined with the traditional desire of rural couples for a son to look after them in old age, the policy has been particularly catastrophic for girls, resulting in neglect, infanticide and - when ultrasound and other sex selection techniques became widely available - gender-specific abortions.

Although it is often called the "one-child" policy, China's family planning policy has been more complex. Rural parents and ethnic minorities have often been allowed more children.

And it is fair to say that while abhorring some of the excesses of the policy and mourning the consequences for their own families, many Chinese have supported the policy in principle on the grounds that the population was too large and personal sacrifice necessary for the common good.

But when I think about the numberless personal tragedies this policy has produced, faces and stories crowd my mind.

I know little boys who are only alive because a pre-natal ultrasound promised they would be boys.

Children grow up with undivided attention from parents and grandparents - but they will have to look after them when they age

I know families where little girls died mysterious deaths. I know women who now suffer lifelong gynaecological problems because they hid in the hills when they were due to give birth in order to avoid forced abortion at the hands of roving family planning police. I know whole families blighted by the weight of the fines for a child born outside the plan.

And what of the Chinese children who were lucky enough to be born in the past three and a half decades?

For them there is often the psychological pressure of single-handedly meeting the expectations of two parents and four grandparents who have strained every sinew to house, clothe, feed and educate them... not to mention the economic pressure of single-handedly looking after these parents and grandparents as they age.

No panacea?

China says its family planning rules have prevented hundreds of millions of births and made possible its economic miracle - by freeing women to go out to work and by encouraging saving.

But critics always said China's birth rate would have come down with or without the policy as it industrialised, pointing out that other developing Asian countries have seen a comparable decline without such Draconian policies.

And now China has the opposite problem - an ageing population and a shrinking workforce.

The policy came into effect under Chairman Mao Zedong and became national policy in 1979

China may get old before it gets rich. Or worse, the burden of the aged may prevent it getting beyond middle income status at all.

But if the declining birth rate was driven by underlying economic incentives rather than family planning policy, then it is unlikely relaxing the policy will solve the problem.

After all, China is now a predominantly urban society where parents count the costs when making a choice about children.

It is also a society where both parents usually work.

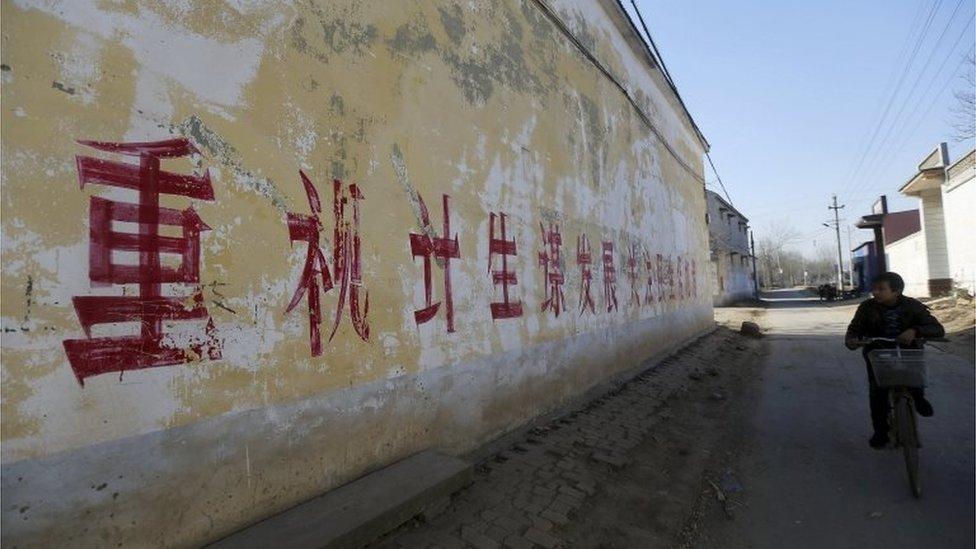

Here in a village in Hebei province, a slogan reads: "Pay attention to One-Child Policy and seek developments"

A bigger family means increased costs and reduced earnings and the evidence to date suggests many parents will choose against that.

In the past two years, a relaxation for those who were themselves only children allowed more than 10 million couples to have a second child. But fewer than a million applied, less than half the number the government expected.

In the richest cities, the reluctance is even more pronounced. In Shanghai, for example, the Family Planning Commission recently estimated that 90% of women of child-bearing age were eligible for a second child under the rule change of 2013, but that only 5% had applied.

So as it finally announces the end of the one-child policy, the irony for the Chinese government may be the discovery that the policy had become irrelevant anyway.