The personal cost of China's one-child policy endures

- Published

The one-child policy had been in place for 36 years

China's long-standing one-child policy is no more. Its impact, however, has affected generations.

Two Chinese people tell us their stories - one who grew up without siblings, and a mother who could not give her daughter any.

'Everyone knew the rules'

By Juliana Liu, Hong Kong Correspondent, BBC News

When experts estimate that about 400 million babies have been lost as a result of the one-child policy, I sometimes wonder if my two younger siblings have been counted among them.

After I was born in 1979, when the policy was introduced, my parents were forbidden from having any more children.

They were the first in their families to become salaried employees in the big city.

Violating birth planning regulations would have got them sacked.

They would have had to return to the countryside, to the back-breaking agricultural work that their ancestors had done for millennia.

Everyone knew the rules.

John Sudworth examines the painful legacy of China's one-child policy

Yet, like so many others, my parents longed for more children, for the kind of large, boisterous clan that Chinese culture, with its rural roots and tradition of ancestor worship, still values so highly.

When my mother became pregnant twice again, she had no option but to abort both of them.

Today, as a mother myself, I cannot imagine what it is like to have to end the life of a deeply loved, wanted child.

But ours was not a unique story.

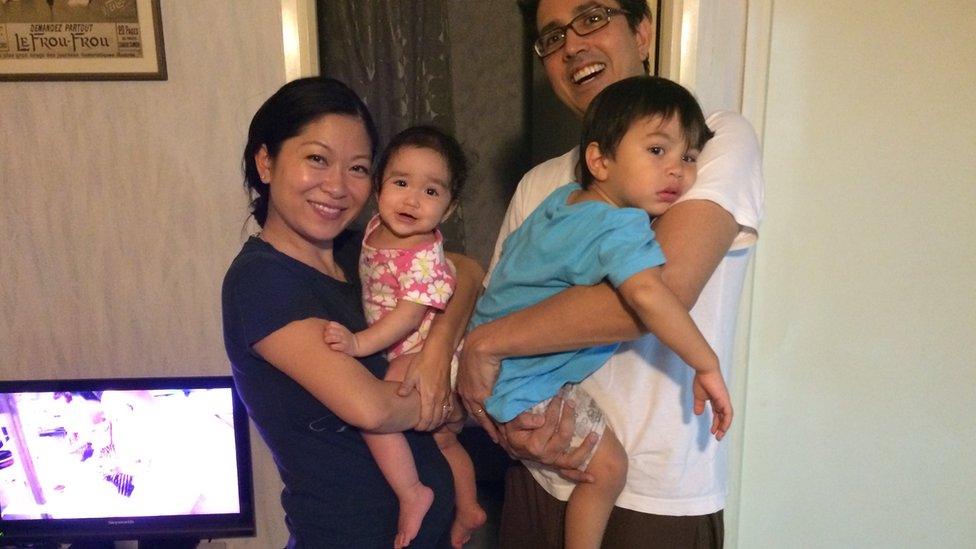

The BBC's Juliana Liu, pictured with her family

Nearly every family in China has been touched by the one-child policy.

Growing up in my parent's work unit, none of my playmates had any siblings.

We were spoiled, pampered. We got the best that our parents could give.

At the same time, even from a young age, each of us knew very well that we, alone, carried the expectations of both sides of our families on our tiny shoulders.

It was, at times, difficult not to feel crushed by the weight of those expectations: to excel at school, to be well-behaved, to be filial, to have a prestigious career, to marry the right person - in short, to be perfect enough to justify the fact that there is only one of you.

I am sure some of my friends felt differently, but all through my own childhood, I longed for at least one sibling to share the burden, the responsibility, and the occasional fun of being an only child.

The feeling has become only more acute as my parents approach old age.

All Chinese couples will now be allowed to have two children

That is why I was overjoyed to hear that the one-child policy would be replaced by the two-child policy.

It is far from perfect. The government still controls what should be deeply personal, family decisions.

But it is clearly an improvement on the existing policy. My years in China would have been enriched immeasurably by the presence of a sibling.

I know my parents still grieve for their unborn children.

I mourn them too.

From five to one

By Yuwen Wu, BBC Chinese

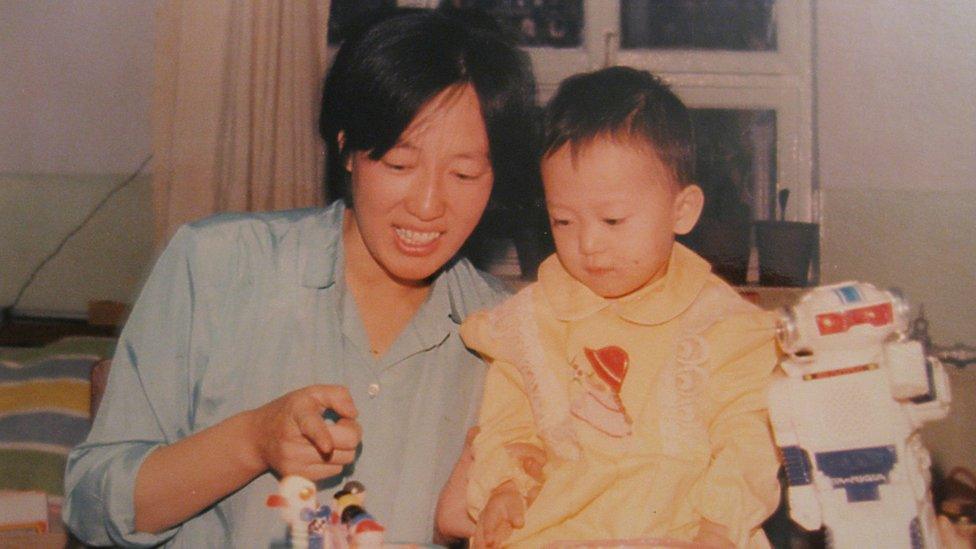

"In my heart, I know how much I wished I could give her a sibling"

Many young Chinese people say they may not be ready to take up the offer of having a second child, as they mull over the prospect.

Lucky them. At least they have the choice. Millions of my generation didn't.

The one child policy was in full swing by the time I was contemplating parenthood, with a deafening propaganda campaign.

I was teaching at Peking University. We all wanted careers, and everything had to be right for that one chance of motherhood.

The university needed to be informed and give approval; the neighbourhood committee was told; and you chose a hospital for the birth.

I was thrilled at the birth of my beautiful daughter. She seemed so much more precious because she would be my only child.

We all supported the policy. We understood that China needed it so it could continue to support the already huge population. Some personal sacrifices were worthwhile.

But deep down, we were all bitter at crude restrictions on our basic rights, especially when we know that the government could have acted long ago.

China's one-child policy explained

China's first census under Communist rule, in 1953, showed a population of over 600 million - growth of 100 million in the previous four years.

Ma Yinchu, president of Peking University at the time, was concerned that the birth rate was too high, the growth rate too fast. He conducted field research, and even spoke before Chinese leader Mao Zedong himself about the need to control the population.

Mao did not like this at all. He branded Ma's work as challenging the party's authority. Ma was sacked and lived under house arrest for many years afterwards.

No action was taken. The prevailing thought was more population meant more manpower and was good for socialism. People were encouraged to have big families and women who had had a lot of children were even given awards.

I was the fifth and youngest child in my family, a typical size at that time. Having a sister and three brothers ensured that I was well looked after, and had many fun things to do.

The policy has left China with an ageing population and grandparents often left caring for children as parents work

But we each had only one child. We tried our best to nurture good relationships among the cousins, but it was not the same.

"How can things be this different from one generation to the next?" we wondered.

My mother said she would have accepted a two-or- three child limit - but nobody asked her. My brothers would always tease me, "then you wouldn't be here".

I am grateful I am here, but I feel angry that political leaders didn't respect science decades ago. We have suffered the consequences.

Growing up alone, my daughter learned to make friends and have good judgement. She is independent and hard working. I am very happy she turned out the way she has, but in my heart, I know how much I wished I could give her a sibling.

History doesn't allow "what if" scenarios. I just hope that today's policy makers monitor the situation and listen to science, so another generation doesn't have to make sacrifices on such a basic human issue.

- Published29 October 2015

- Published30 October 2015