Could Brexit mean a new UK-China relationship?

- Published

Brexit will mean Britain having to find new economic partners, so what are the prospects of a stronger trading relationship with China?

Afternoon tea in the Shanghai Peninsula Hotel is reminiscent of the days when the British ran the world's greatest trading empire.

Then, as now, Shanghai was the money capital of China and afternoon tea was a ritual featuring crisp tablecloths, silver tea service and business gossip.

The big difference now is that Britain no longer runs the empire. With a population 20 times as large, China has the scale advantage and the shoe is now on the other foot.

The last British government worked hard at attracting Chinese investment, embarking on what it called a golden decade with Beijing. But the new prime minister has delayed a key nuclear power project, reportedly due to concerns about Chinese involvement.

So just as Brexit Britain is looking to new economic partners to replace the European Union, will national security concerns rock its relationship with China?

Across the table from me, sipping English tea (milk, no sugar), Joselyn Zhou is untroubled. She acquired the English tea habit last year while studying for an MBA at Durham University.

At 34 years old, this Shanghainese is already a business veteran. And while studying in the north-east of England, she kept close watch on small British enterprises she believes have the potential to make it big in China.

Her first target is a digital platform for occupational training courses, as she believes China has the technology but not enough content.

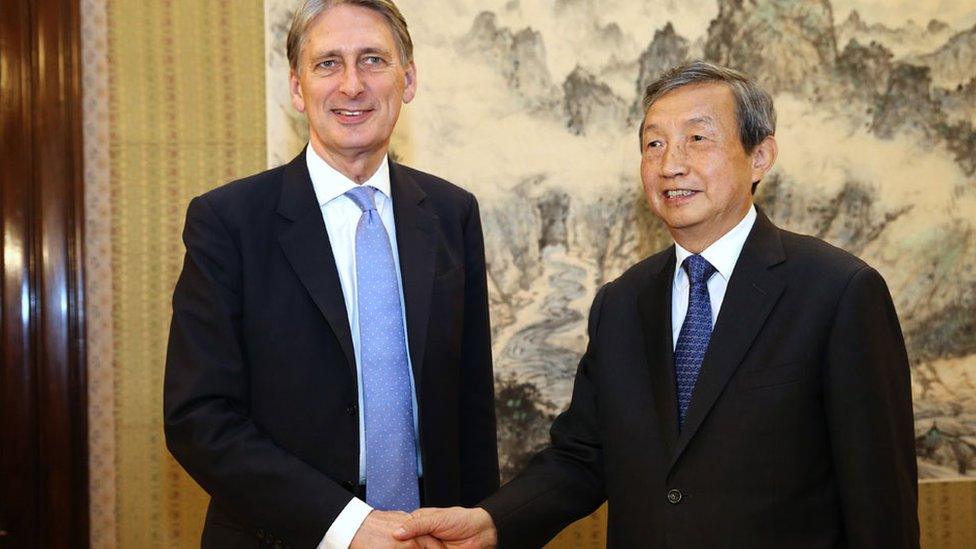

Britain's Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond with Chinese Vice-Premier Ma Kai. The UK has worked hard to secure Chinese investment

"From my perspective, the UK is still an attractive destination," she says.

"It is a centre for talented people. If you can retain that quality and attract bright business talent in, I don't see any negative effects.

"And for a new prime minister, checking everything is reasonable. I don't see long-term tension. The two countries will solve things in a diplomatic way."

In Ms Zhou's view, whether it is a company or a government, when facing the might of China, it all comes down to having something worth selling.

When the UK leaves the EU and has to negotiate trade deals with China alone, she says, it will have less leverage, so quality will be even more important.

"You have nations that are small but their standards and quality are high, so it is all about what you have to offer," she says.

China's moneyed classes are still eyeing smart London properties

Ms Zhou is not the only one optimistic about the future of the UK-China relationship.

Larry Wang runs a consultancy arranging visas for Chinese investors in the UK and has seen intense demand post-Brexit.

"The UK remains a dream country for lots of Chinese people. If possible they would like their children to be educated in the UK for a period of time," he says.

"They don't make decisions on political reasons, but on their own economic benefits. It doesn't matter if the UK remains in the European Union or not."

A lawyer I get chatting to on a train tells me the British bargains for China's moneyed classes go beyond education, to holidays, property and business.

"If there is an opportunity for them to invest and they see valuable assets, that will prompt an overall investment shopping spree," he says.

"And as a tourist, everything is more affordable.

"Basically, China has never been this rich, and London has never been this affordable."

He himself is about to take his family to the UK on holiday, and many of his friends are buying property.

But he urges the British government to quash doubts about Chinese intentions and national security.

"There are people who are very sceptical and suspicious about Chinese expansion worldwide," he says.

"To me, this is not justified. Everyone needs to make money.

"You really should grab this opportunity and maximise your profit.

"That is what English people are very good at."

The most sombre assessment of British prospects I meet in China this week comes from a man who still has to promote them.

Britain's decision to delay a final decision on Hinkley Point was unexpected and thought to be due to concerns about Chinese involvement

Joerg Wuttke represents the European Chamber of Commerce, and, while acknowledging the UK's strong financial services, soft power and good will in China, he gave me a long list of reasons to be gloomy about what will happen when the UK finally leaves the EU and has to negotiate its own trade deals with China.

"It's going to be difficult," he says. "First, the Chinese hate uncertainty. Second, you have past promises that when you enter London you're in the middle of Europe. This is not the case any more. Thirdly, if you invest heavily in the United Kingdom and then have your currency devalued by 10%, that already sends a message to Beijing.

"And the last point, Hinkley Point… is the UK a trusted partner when it comes to Chinese companies operating a nuclear power station or not? For China, this is very difficult to swallow possibly. Are we trusted partners or not?"

Is the list long enough? Mr Wuttke is also worried the UK does not have enough experienced trade negotiators to handle negotiations. And it is at this point that the real challenge begins.

"It will find it has no leverage," he says.

"The UK already has the most open market. China's is closed. China doesn't trade on good will; you have to trade with something.

"For the UK, it will take five to 10 years if it wants to negotiate a free trade agreement."

The irony is that what was intended as a golden decade for UK-China ties may turn into a tortuous decade of trade talks.

But at least there will be British bargains for Chinese buyers along the way.

- Published24 July 2016

- Published31 July 2016